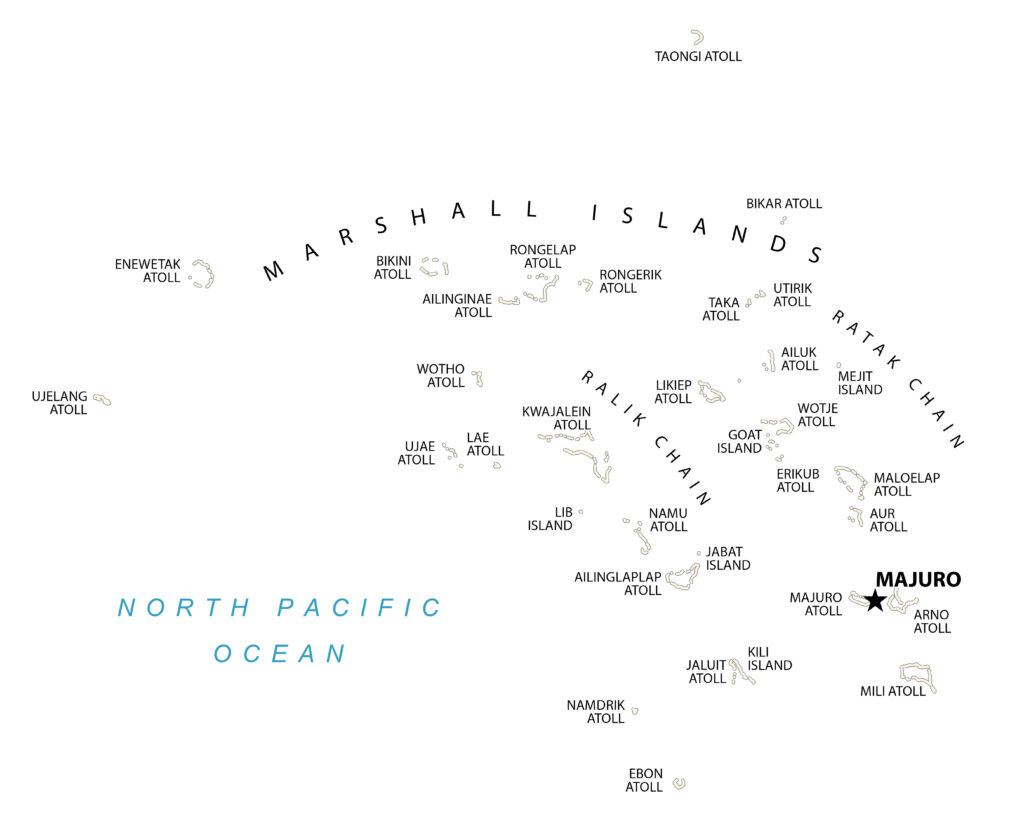

They traveled from around the world to a most unlikely meeting point. Some flew from London, others from Tokyo, Delhi or Atlanta. For all, it was a long journey, even for the Marshallese, who traveled 36 hours by boat from Majuro, the capital of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). They assembled on Ebeye, an 80-acre island and among the most densely populated places in the world. Ebeye is one of nearly 100 islands that make up Kwajalein, one of 29 coral atolls in this large ocean state.

The 30 artists, filmmakers, storytellers, scientists, researchers, activists, and academics gathered to participate in a project called Kõmij Mour Ijin, which translates as “Our Life is Here.” The project was designed to recruit and transport Marshallese and international artists and creative thinkers on a 12-day journey across hundreds of miles from Kwajalein (where the United States operates an army garrison and ballistic missile test range) northward to the atolls of Wotho, Bikini, and Rongelap. Some of the artists had never been to the Pacific before, while others were born and raised in the Marshall Islands, and one was a respected ocean navigator and former mayor of Bikini Atoll.

The Kõmij Mour Ijin project was the vision of American photographer Michael Light, who had been doing underwater shoots in the northern Marshall Islands, where the legacies of colonialism and nuclear weapons testing converge with the existential threat of climate change.

Light, who first visited the RMI in 2003, was deeply moved by what he saw on the islands and below the waters of Bikini and Enewetak atolls, where the United States conducted 67 nuclear weapons tests between 1946 and 1958. He described Bikini as a “tremendously difficult, dark, and violated landscape,” where “the nuclear legacy alone is heavier than the specific gravity of lead.”

Upon a second visit in 2007, after taking aerial photographs of the crater caused by the first test of a thermonuclear weapon at Enewetak, Light was left shaken and deeply unsettled. His mood was dark, and he vowed that if he ever returned, it would have to be with others who could share the experience and bring their impressions to a larger, global audience.

In 2018, Light met British artist and filmmaker David Buckland, founder of Cape Farewell, a foundation that connects artists and scientists with the aim of interpreting, and ultimately shifting, humanity’s trajectory away from environmental destruction and climate change. Buckland, who has worked extensively in the Arctic, joined Light in traveling to Majuro, where they began a series of conversations with poet, educator, and climate activist Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner about how to turn their vision into reality. They agreed that a project based only on international artists, no matter how skilled, would be of limited value without including creative young Marshallese.

But as the project began taking shape, the world started coming undone. In March 2020, COVID-19 swept across the planet, travel halted, and borders closed. There would be no journey to Bikini or anywhere else while the pandemic raged.

“It was given to us inside a seed, so we planted it in the soil. As the tree grows, the canoe grows inside the seeds. It’s like a gift covered with branches and leaves. All we did was chop away the skin to bring out that canoe.”

Alson Kelen

The global shutdown did, however, give organizers time to plan and seek proposals from potential participants. Jetñil-Kijiner, who serves as a climate envoy for the RMI, is co-founder and director of Jo-Jikum, a nonprofit youth group dedicated to building Marshallese leaders and change-makers. Jo-Jikum program manager Konea Ishimura helped recruit thoughtful, creative young Marshallese. Considering the role of the artists, Ishimura says, “We can use their artistic lenses to put the word out there. Something that became clear to me throughout this trip is that the issues of climate change and nuclear legacy have not been fully communicated until it’s been communicated through art.”

Marshallese participants included six young artists, respected master weaver Susan Jieta, and two canoe builders and navigators, Alson Kelen and Clancy Takia. The international cohort of artists came from New Zealand, India, Japan, Mexico, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

North to Bikini

Such a large group had to be divided into two boats — the ten-passenger M/V Surveyor and the M/V Pacific Master, which sleeps 20. From Ebeye, the boats sailed northward some 150 miles to Wotho, a comparatively small, rarely visited atoll. The brief visit to Wotho gave participants an opportunity to experience rural life. While there, Wotho community members prepared a special welcome ceremony followed by a shared meal, singing, dancing, traditional chants, and the recitation of ancestral affiliations. The visitors offered gifts of useful provisions as is customary for such a first meeting.

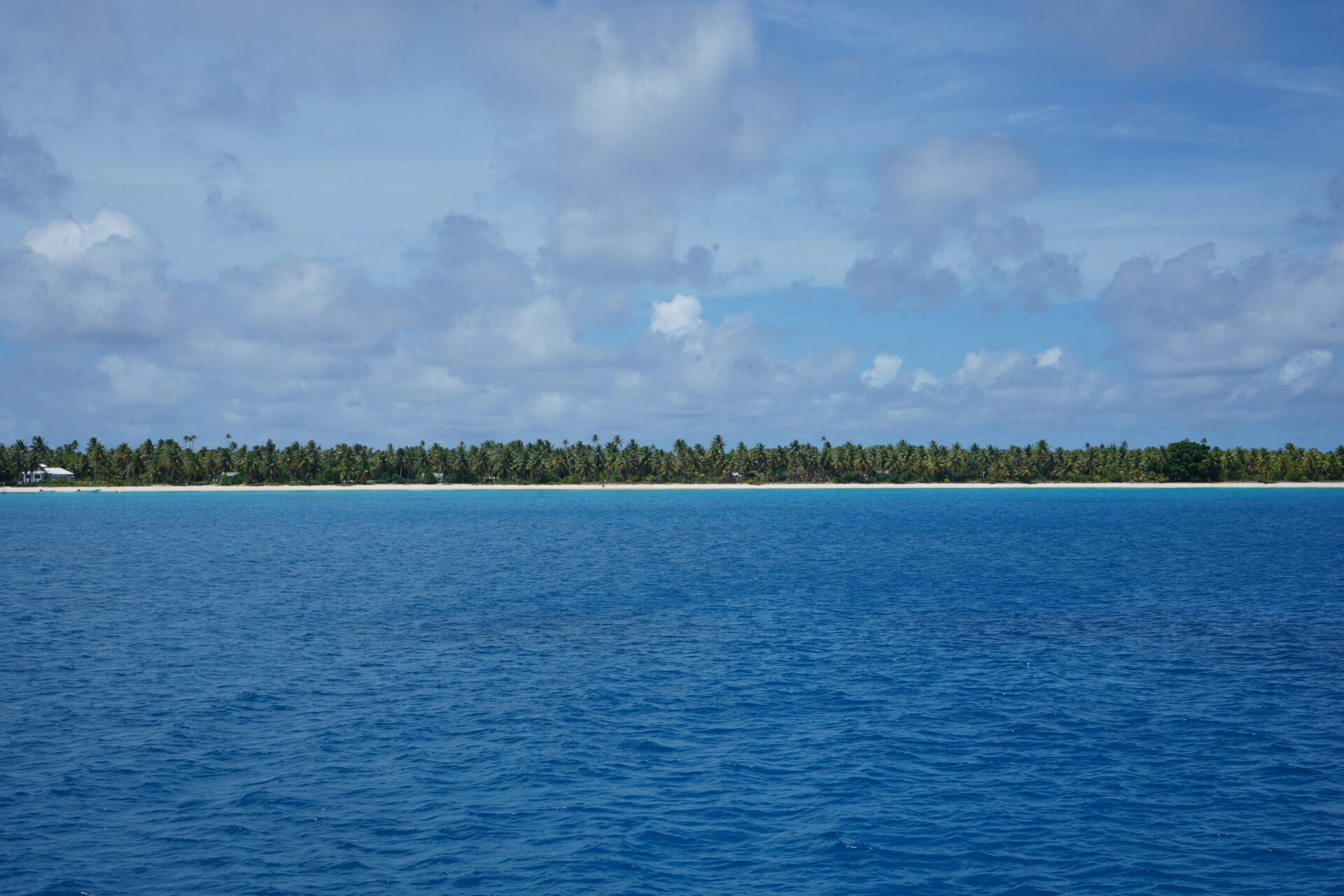

From Wotho, the boats continued northward another hundred miles, across the turbulent north Pacific to Bikini Atoll, a place once called Bukinni, meaning a “dense group of coconuts.” But when they arrived, there was no community to welcome them and no gifts to offer. The people of Bikini, like those on neighboring atolls, had been driven into exile by the nuclear tests.

Jetñil-Kijiner says that for the foreign artists spending time at Bikini, a place even few Marshallese visit, there comes a level of responsibility and the need for open, honest conversations about the intentions of each artist and discussions of culture, history, and power imbalances.

“There’s a kind of weird level of exotification of the nuclear testing that can exist with some people in a really ugly way,” she says, pointing to the tokenization of Marshallese people. From “atomic cakes” and “Miss Atomic Blast” showgirls to animated cartoons and even the name Bikini itself, nuclear weapons testing has been minimized, trivialized, and appropriated with little regard for the deep generational trauma caused by the tests.

Visiting Bikini and Rongelap, where entire communities were forced to relocate and permanently abandon their homeland because of US nuclear tests, invokes emotions of sadness, grief, and loss.

Jetñil-Kijiner sees a throughline in the historical colonization of the Marshall Islands, the nuclear testing era, and climate change. In each of these, she says, the Marshall Islands have been deemed to be less important than other places and accepted as a “sacrificial zone.” She explains that “The Marshall Islands was seen as this vast, empty place in the middle of nowhere.”

She asks, “In the middle of nowhere to who?”

“A lot of our work is telling that story to say we’re not a sacrificial zone. There are people here,” Jetñil-Kijiner says, explaining how the value of this project is to remind the world that “We live here. Our life is here.” The ongoing task of advocating on the international stage, Jetñil-Kijiner says, is a continuation of the work spearheaded by the late Marshallese statesman Tony de Brum.

“I don’t think that it will ever end because we have to keep reminding people that our humanity matters, and this shouldn’t be a sacrificial zone,” she says. When people shake their heads at the horror of nuclear weapons, lamenting the “tragedy that man has committed,” Jetñil-Kijiner begs to differ. “No. There was a very specific race of people and countries who have committed these kinds of atrocities. The rest of us have just been living our lives. I think we can be really clear about that.”

For the Good of Mankind

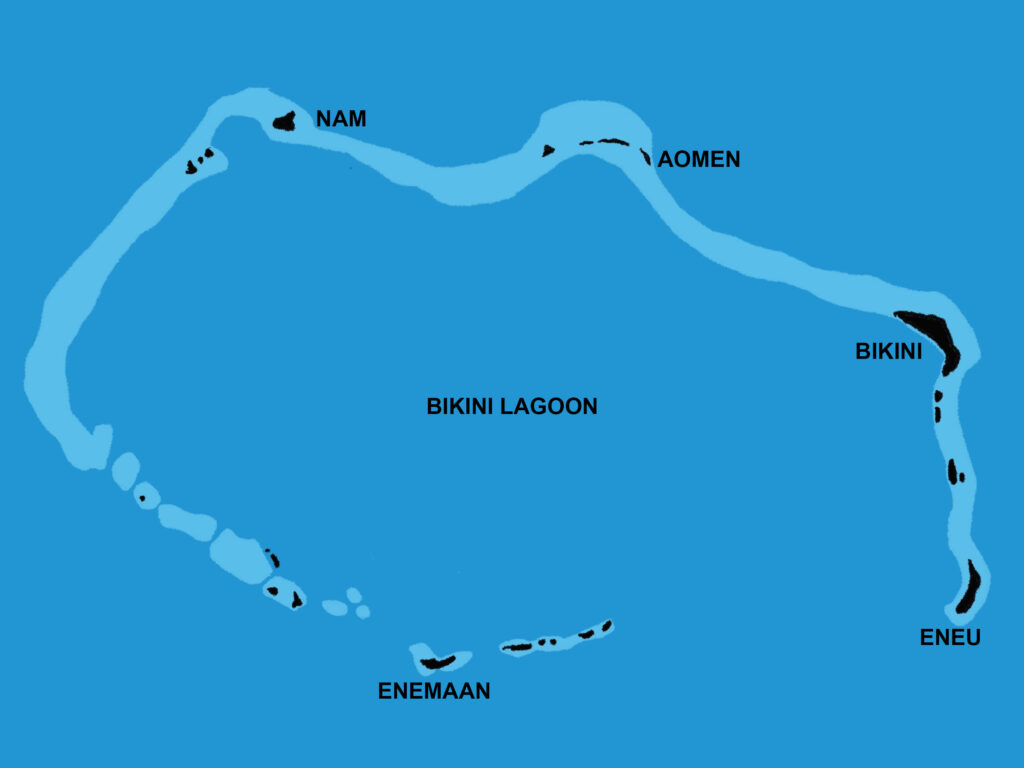

The United States detonated 23 nuclear explosions at Bikini, accounting for 72% of the total yield of all nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands. In the northwest quadrant of Bikini, beside a small island called Nam, on March 1, 1954, the United States detonated a 15-megaton hydrogen bomb code-named Castle Bravo, the largest US test ever conducted. US officials blamed a larger-than-predicted blast and unexpected shift in the winds, but the test scattered radioactive debris, which rained down like deadly snowflakes onto other populated atolls and eventually spread far beyond.

When considering the violence and destruction the United States unleashed on these islands, it is rarely mentioned that in its last two years of testing (1956 and 1958), the United States conducted at least seven back-to-back nuclear tests on consecutive days and seven instances when it detonated two nuclear bombs on the same day at Bikini and Enewetak atolls. Those tests had deceptively peaceable names like Aspen, Cedar, Maple, and Sycamore.

After Commodore Ben H. Wyatt told the Bikinians that they were being relocated “for the good of mankind,” the forced removal and loss of ancestral homelands was a gross human rights violation to a people who gave birth to one of humanity’s most advanced cultures of ocean navigation.

The nuclear testing era, which followed centuries of colonization by the Spanish, Germans, Japanese, and Americans, was a precursor to the coming threat of displacement from another external force. Today, climate change is causing destructive storms, sea level rise, saltwater intrusion, and droughts that could render low-lying coral atolls uninhabitable long before the sea covers them.

For the Marshallese, especially the four Bikinians, the arrival at Bikini was bittersweet and infused with deeply conflicting emotions. For Kelen, it was truly a homecoming. Kelen, a master navigator and respected elder (although he’s still 55), previously served as Bikini’s mayor (2009-2011) and is now one of three commissioners on the RMI’s National Nuclear Commission.

As a young boy, Kelen lived on Bikini with his grandparents from 1974-78 when around 100 Bikinians had returned to the atoll before being re-evacuated due to health concerns. Kelen recalls his childhood, waking to the sound of his grandfather chopping wood used for making canoes. Kelen watched curiously each morning as his grandfather chopped away.

“What’s going on, jimma? Is this your hobby?” Kelen asked his grandfather.

“We’re canoe people! We need vessels to go out and bring fish in,” his jimma answered.

The young Kelen enjoyed the abundance of Bikini’s 23 islands and lagoon that, at 460 square miles, provided for its people with traditional foods like coconuts, breadfruit, pandanus, arrowroot, reef fish, coconut crabs, and lobster.

Nuclear testing, however, drove Bikinians from their ancestral homelands, forcing them to relocate to other atolls and islands that were much smaller and more difficult to live on. Today Bikinians live throughout the RMI and in the United States in places like Arkansas, Hawaii, and the Pacific Northwest. The overwhelming majority of young Bikinians have never set foot on Bikini.

Mourning Islands

Alongside Kelen, were three young Bikinian artists. One of them, Victoria Jamore, recalls seeing photos of her late father who, like Kelen, served as Bikini mayor, but she and her brother Jewan, who was also on board, had never visited. For Jamore, arriving in Bikini evoked a complicated mix of emotions — guilt, gratefulness, joy, responsibility, and heartbreak. Over the course of the three-day stay, she gradually felt more comfortable and realized she had the opportunity to share photos with other Marshallese, reminding them, especially young Bikinians, that Bikini is still there. “This is your home,” she says, “never forget the legacy that has been left here on this island, and remember why we can’t go back.”

Jamore recalls the haunting sound of waves echoing across the lagoon, surrounded by empty, lonely islands. “It kind of felt like the island was crying. I felt like it was kind of happy there were people on island, but also you could just hear the island mourn.”

Jamore and fellow Bikinian Giovannie Johnson traversed the lagoon in an 18-foot-long “korkor” (sailing canoe) piloted by canoe builder Clancy Takia. That canoe, built by Kelen’s students with the wood of breadfruit and a tree called lukwej (Calophyllum inophyllum), is the embodiment of a culture based on early Marshallese navigational chants that recall how the first canoes were invented at Bikini Atoll. Kelen pointed out that this was the first time Bikinian women had sailed in Bikini’s lagoon in 77 years.

Upon arriving at Bikini, Johnson felt a heaviness creeping over her. Looking onto shore, seeing abandoned houses, she felt a cold chill. She adds, however, that she saw the resilience of nature in what she describes as a “motherland untapped.” She left Bikini with a renewed appreciation and respect for her own culture and the hope that future generations would also one day return to Bikini, at least to visit.

Johnson accompanied Kelen to visit his family graves, listening as he recalled his childhood when he and his grandparents were told they had to leave Bikini again because the government determined it was not safe after all. Now that he had returned, if only for a few days, Kelen knew something was missing from Bikini. This voyage was his chance to bring back the Bikinian’s most cherished possession — a canoe. It is the canoe, Kelen says, that is the most important tool, a vessel that not only carries people, food, and supplies, but culture itself, along with the knowledge to survive and a sense of identity.

Knowing how to build and sail a canoe is not only a symbol of the past, it is a compass and map leading through the troubled present to an uncertain future. The canoe, Kelen says, provides access to education, opportunities, and the sustainable lagoon transport the Marshallese will always need. “The same ocean that has provided resources to us is crawling closer and closer to our living rooms,” says Kelen. “This country needs to shift from what it is today to what it was and what it will be. That’s why I thought we need to do this. At least we owe something to the canoe island.”

When Kelen lowered the canoe into the lagoon and he first set sail, his hair stood up, and he cried. This was his chance to experience what his ancestors might have felt, coming into the island, carrying fish and breadfruit to feed their families. The canoe was the gift Bikini gave to its people, says Kelen. “It was given to us inside a seed, so we planted it in the soil. As the tree grows, the canoe grows inside the seeds. It’s like a gift covered with branches and leaves. All we did was chop away the skin to bring out that canoe.”

On their final day at Bikini, Kelen, Takia, and half a dozen others hoisted the canoe out of the lagoon, carried it up onto the beach beyond the water line, and set it down in the sand, its sail rolled up and ready. There it was left as a gift, a gesture of gratitude that would remain long after the people had gone.

Is It Safe?

The Surveyor and the Pacific Master departed Bikini, making the rough 13-hour crossing to Rongelap Atoll. As twilight fell, Bikini faded into the background, bathed in fading light while a crescent red moon rose over the darkened seas, lightning flashing in the distance. In the morning, they arrived at Rongelap, which like Bikini, is all but abandoned, having been evacuated after the Bravo test in 1954. Rongelap was partially repopulated, only to be evacuated again in the 1980s.

One member of the group, Greg Dvorak, a Tokyo-based cultural studies professor at Waseda University, was raised on Kwajalein in the 1970s and 1980s. He continues to research and write about the Marshall Islands and was eager to see Rongelap for himself.

The intense grandeur and seductive beauty of Bikini and Rongelap, Dvorak says, belies the tragedy that has been imposed from outside. The resilience of the Earth, he says, is incredibly humbling. But diving in Rongelap’s lagoon, Dvorak saw patches of dead coral reef, bleached and covered with shaggy carpets of algae beside healthy coral filled with fish and sharks.

On land, new houses built in the hopes that Rongelapese would return, stand empty today. Dvorak describes well-equipped modern duplex houses that resemble a “little beach community in Florida” but look out of place, overgrown with vines, and buzzing with flies.

Nearby, inside an empty church, a forgotten bible was left open, minister’s vestments hung on a hook, but the interior was damaged by rats and birds. Outside, Dvorak and a few others encountered temporary resident construction workers from Majuro who ask for a cigarette and offer open coconuts and a welcome gesture. But when someone gives you a coconut harvested on Bikini or Rongelap, what do you do? Their Gieger counters, Dvorak says, had higher readings on Rongelap than even near the Bravo crater at Bikini. This question of safety, Jetñil-Kijiner says, “is something Marshallese people live with every day. Is it safe?”

The Power of Art

After a day at Rongelap, both boats began the long journey south — 24 hours to Kwajalein, 48 hours back to Majuro. Now, back in their respective homes, the artists, filmmakers, storytellers, scientists, researchers, activists, and academics are processing what they experienced, considering how to interpret the voyage in their respective media, be it painting, film, photography, performance art, or poetry.

Currently, there is talk of an art exhibition by Marshallese artists, possibly timed for Nuclear Remembrance Day next March 1, 2024. More creative works will follow and perhaps a film, a book, and a traveling exhibition a year or two from now.

Art, Buckland says, can unleash a strong, emotional force for good. “If we get it right, that is a very powerful way of going forward.” Unlike activism which he compares to poking someone hoping they will change, Buckland says art can inspire a change in behavior through the power of seduction. “People would much rather be seduced than poked.”

Jo-Jikum’s Ishimura hopes people will reflect on the meaning of the project’s name — Our Home is Here — and remember that people’s action or inaction will impact people in the Marshall Islands and elsewhere.

Back from Bikini, Dvorak asks, “What does it mean to live here? And where is here?” Exploring questions about colonialism, militarization, power imbalances, exploitation, and use of resources, and who pays the highest costs associated with climate change, leaves people vulnerable and often uncomfortable, but these questions need to be addressed.

“We went to Bikini to explore on an expedition purportedly, but what came out of it was a conversation, and that conversation is like gold,” Dvorak says. Whatever creativity stems from this conversation is not the end of the story, but is perhaps, just the beginning.

All photos were taken in a 12-day period around mid-August 2023.

Hey there!

You made it to the bottom of the page! That means you must like what we do. In that case, can we ask for your help? Inkstick is changing the face of foreign policy, but we can’t do it without you. If our content is something that you’ve come to rely on, please make a tax-deductible donation today. Even $5 or $10 a month makes a huge difference. Together, we can tell the stories that need to be told.