In the midst of the insurrection at the United States Capitol last week, politicians began exporting comparisons to the Global South, defining the moment as inherently un-American. Sen. Marco Rubio called the events “Third world style anti-American anarchy.” Rep. Alan Lowenthal of California said the events “felt like a coup in a third-world country.” And Rep. Mike Gallagher of Wisconsin called it “Banana republic crap.”

The racist, colonial narrative that state-sponsored attacks on democracy are perpetrated solely by Black and Brown political actors from “shit hole countries” in the Global South denies the inherently American nature of this siege. Instead, such narratives promote the US as a perfected democracy, above the electoral violence in Kenya or unrest in Venezuela. Americans’ devotion to its democratic project and unwavering belief in American superiority has resulted in an inability to see or even consider the fragility of our democratic institutions. The political violence that occurred on January 6 was not extraordinary — it was another instance of state-incited violence to uphold existing structures of power and dissuade democratic debate. One which was undeniably American.

The political violence that occurred on January 6 was not extraordinary — it was another instance of state-incited violence to uphold existing structures of power and dissuade democratic debate.

Throughout the past days, media outlets, academics, political pundits, and the US government have tried to categorize the events of January 6. While the Department of Defense classified these actions as protests, others have invoked the terms coup, insurrection, and even domestic terrorism.

To be clear, the assault on Capitol Hill was not a mere protest. Protests and state-incited violence are not the same. In fact, they are fundamentally and analytically different, as social movements emerge from the bottom up — from the seemingly powerless who seek to challenge the powerful elite. State-sponsored violence, by definition, is a top-down phenomenon in which the political elite and powerful employ their monopoly on the legitimate use of force against their enemies — foreign and domestic.

Political elites often mobilize supporters to engage in state-sponsored violence through divisive and inflammatory rhetoric and material resources. While it is highly unlikely that the US offered material support such as funding or intelligence to these insurrectionists, it is clear that the Commander in Chief leveraged his institutional legitimacy to incite and condone the assault on Capitol Hill, an act of intrastate violence.

As such, the political violence that erupted on January 6, 2021, was state-directed. This is evidenced by both President Trump and Rudy Giuliani’s rhetoric not just in the hours leading up to the assault on the Capital, but in the years leading up to this pivotal moment. Government officials and other political elites purposely incited the insurrectionists. The carefully constructed statements made by Trump (“Stand Back and Stand By”) and Guiliani (“Trial by Combat”) were meant to provoke violence against American institutions. These seditious calls for action were intended to disrupt democracy and offered legitimacy to the insurrectionists.

While the siege is a clear example of state-incited violence, politicians have been quick to characterize the events as beyond comprehension, based on the claim that the US is above such behavior. They draw from culturally-held conceptualizations of American democracy and righteousness, grounded in religious myths of divine purity and American exceptionalism. As a consequence of such narratives, Americans often struggle to critique our political and social institutions. American state-sponsored violence becomes an unimaginable fluke comparable exclusively to the Global South, rather than our own history.

This is simply not the case. US history is full of examples of state-sponsored and state-condoned violence, intertwined with legacies of colonialism and white supremacy. The failure to compare these events not only disregards American violence within our borders and abroad, but it is also rooted in problematic and racist classifications that reify distinctions between the Global South and North.

For instance, American exceptionalism supports international discourse that portrays the US as the world’s police and exports its political violence elsewhere. Indeed, the US has supported non-state and state terrorist actors all over the world, including the death squads in El Salvador and the Contras in Nicaragua. This legacy of state-sponsored violence does not solely extend overseas — the US was founded through the colonization, forced removal, and extermination of Indigenous peoples.

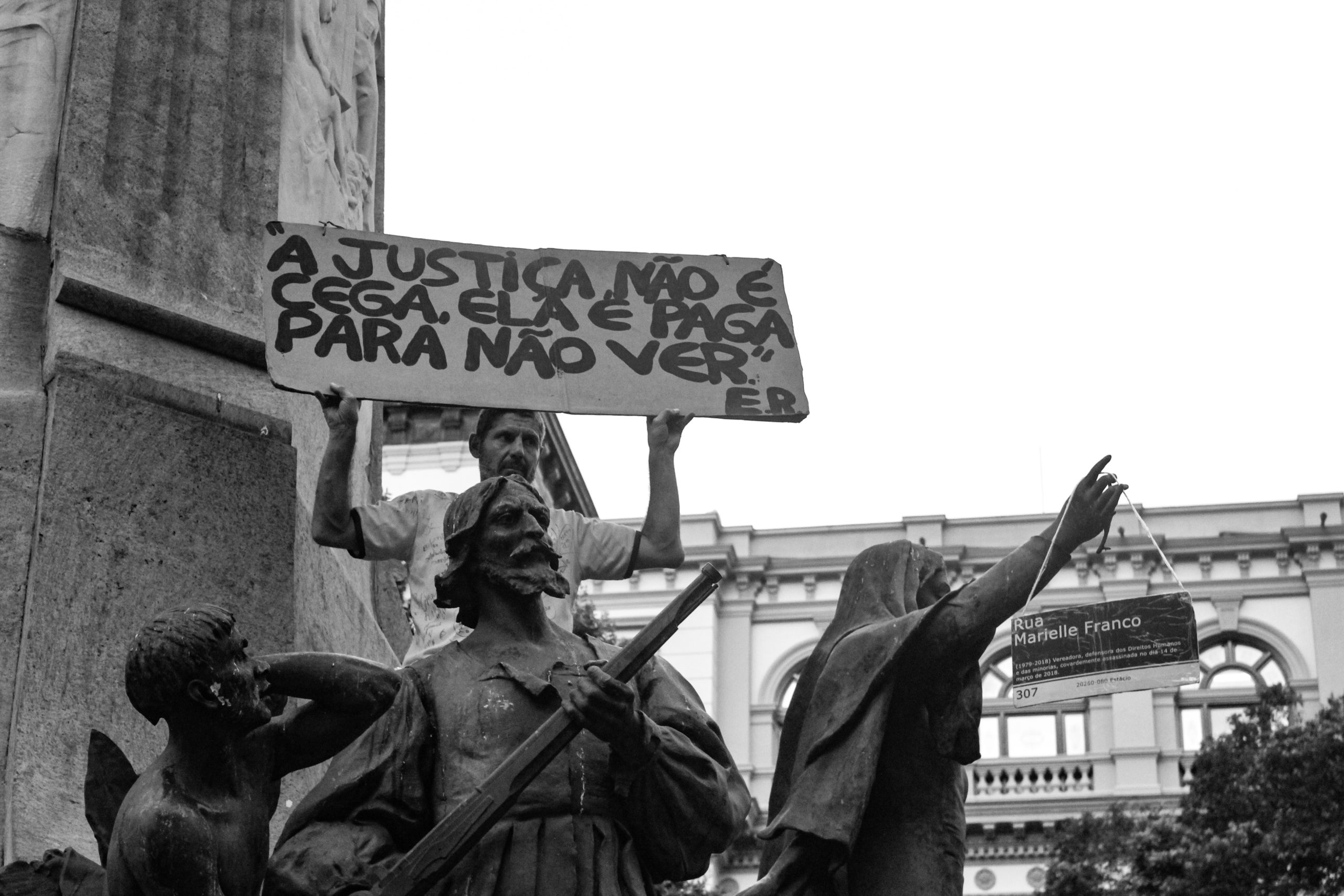

Declarations that the siege is comparable only to the Global South also reinforce global divisions in power. International institutions are built upon hierarchies of justifiable violence and governance. Condemnations of insurrection in the Global South reduce actors to tropes of savage perpetrators and helpless victims, ignoring their agency and complexity. This results in the erasure of long-established resistance to state-sponsored violence in our discourse. Rather than putting ourselves on a pedestal, Americans grappling with this moment could learn from inter-ethnic organizers who resisted dictatorship in the former Yugoslavia or how and why individuals were mobilized during the electoral violence in Kenya.

Although politicians such as President-elect Joe Biden have characterized the assault on Capitol Hill as unimaginable and un-American, American history shows that this episode of political violence was both predictable and consistent with past violence — in fact, American militarism and exceptionalism abroad likely paved the way for right-wing insurrection. To understand this recent ploy to disrupt the democratic process, we must view the events of January 6 as inherently American. The narrative that America is the land of the highest morality, an ideal democracy specifically in contrast to other democratic nations, lends itself to the untrue sentiments we’ve seen in recent days. We must directly confront American exceptionalism and realize that the US is not above state-sponsored violence; it is, in fact, the American way.

Jillian LaBranche (@JillianLaBranc1) is a Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology and the current Badzin Fellow in Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota. She holds an MA in International Human Rights from the Josef Korbel School of International Studies and studies political violence in Rwanda and Sierra Leone. Her dissertation seeks to understand how societies that recently experienced large-scale political violence teach about this violence to the next generation.

Brooke Chambers (@brookebchambers) is a Ph.D. Candidate in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Sociology. Her research interests include collective memory, political sociology, genocide, and the law. Her dissertation work examines generational trauma in contemporary Rwanda, with a focus on the commemorative process. She is the 2018-2019 Badzin Fellow in Holocaust and Genocide Studies and a 2019-2020 Fulbright Research Fellow.

Nikoleta Sremac (@NikaSremac) is a Ph.D. student in Sociology at the University of Minnesota. She studies gendered power relations and collective memory of mass violence in ex-Yugoslavia and the US. Her current research focuses on feminist memory activism in Serbia.