On Feb. 15, 2023, Human Rights Watch released a report that accused the US and UK governments of crimes against humanity and racial persecution for their treatment of the Chagossians, an Indigenous people the two governments forcibly displaced during construction of the US military base on the British-controlled Indian Ocean island Diego Garcia.

Thirty years ago, almost to the day, Human Rights Watch was urged to support the exiled Chagossians by a surprising source: the US Navy official who initiated the plan to build a base on Diego Garcia and exile the Chagossians.

Stuart B. Barber (1914-2002) is the author of the following “archival op-ed,” which was assembled verbatim from unpublished letters to the editor and correspondence Barber wrote in retirement after learning of Chagossians’ fate. Barber’s appeals urging assistance for the Chagossians appear to have gone unanswered.

The US military secretly paid the United Kingdom $14 million for basing rights and the deportation of the Chagossians, who were left in impoverished exile. The US military has since spent billions of dollars building the base. To date, the US government has not acknowledged culpability, paid proper compensation, or assisted the exiled people in returning home.

Barber’s original letters, written to Robert Kaiser (managing editor of the Washington Post), Aryeh Neier (executive director of Human Rights Watch), Honolulu Star-Bulletin, retired navy captain Paul B. Ryan, and Senator Ted Stevens (R-Alas.) between 1975 and 1993, were provided to the op-ed’s curator, David Vine, by Barber’s son Richard Barber during research for Vine’s book, “Island of Shame: The Secret History of the US Military Base on Diego Garcia.”

Below is the op-ed from Barber’s original letters.

“Inexcusably Inhuman Wrongs… At Our Insistence”

It seems to me to be a good time to review whether we should now take steps to redress the inexcusably inhuman wrongs inflicted by the British at our insistence on the former inhabitants of Diego Garcia and other Chagos group islands. The costs would be trivial compared with what we invested in construction.

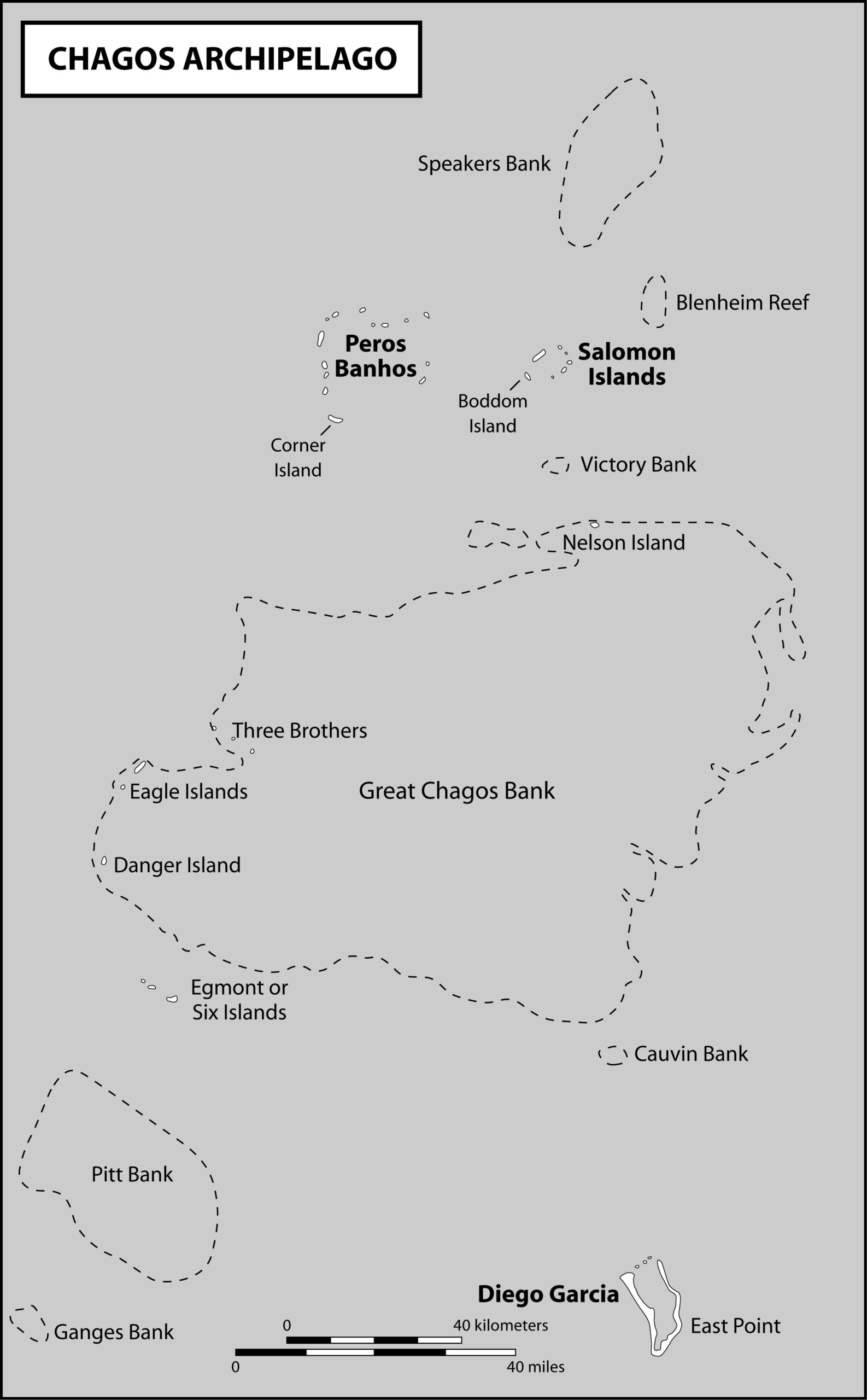

It is too late to undo most of the human damage. But perhaps it will help to allow and assist those evictees who still wish to return to at least the northern Chagos.

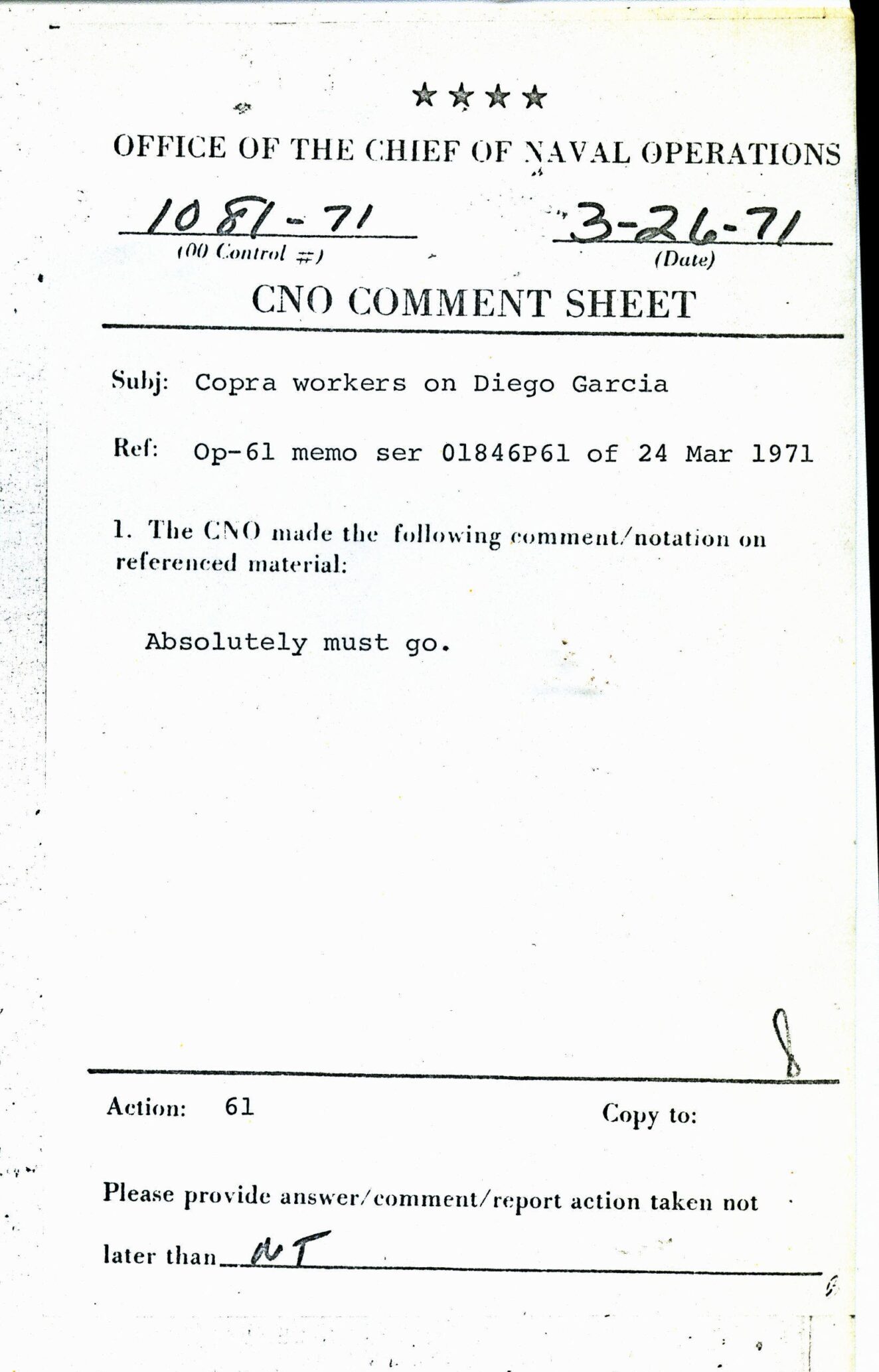

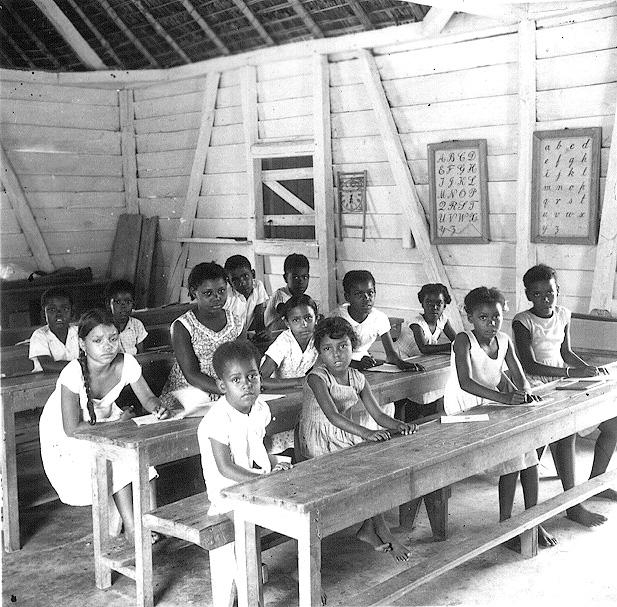

I would assume you are familiar with the miserable history of the eviction of the Chagos Islanders, 1968-73. The concept of setting aside Diego Garcia and surrounding islands as an unpopulated strategic territory for joint US-UK use was initially mine. I personally originated the idea of a modest naval support facility on Diego Garcia, as one component of a large scheme of getting the UK to set aside in a new administrative entity, retainable when all colonies were lost, that and other Indian Ocean islands which might have long-run strategic utility. I think all concerned would agree I became the ultimate pest in monitoring and assisting (self-appointed) the advance of Diego Garcia.

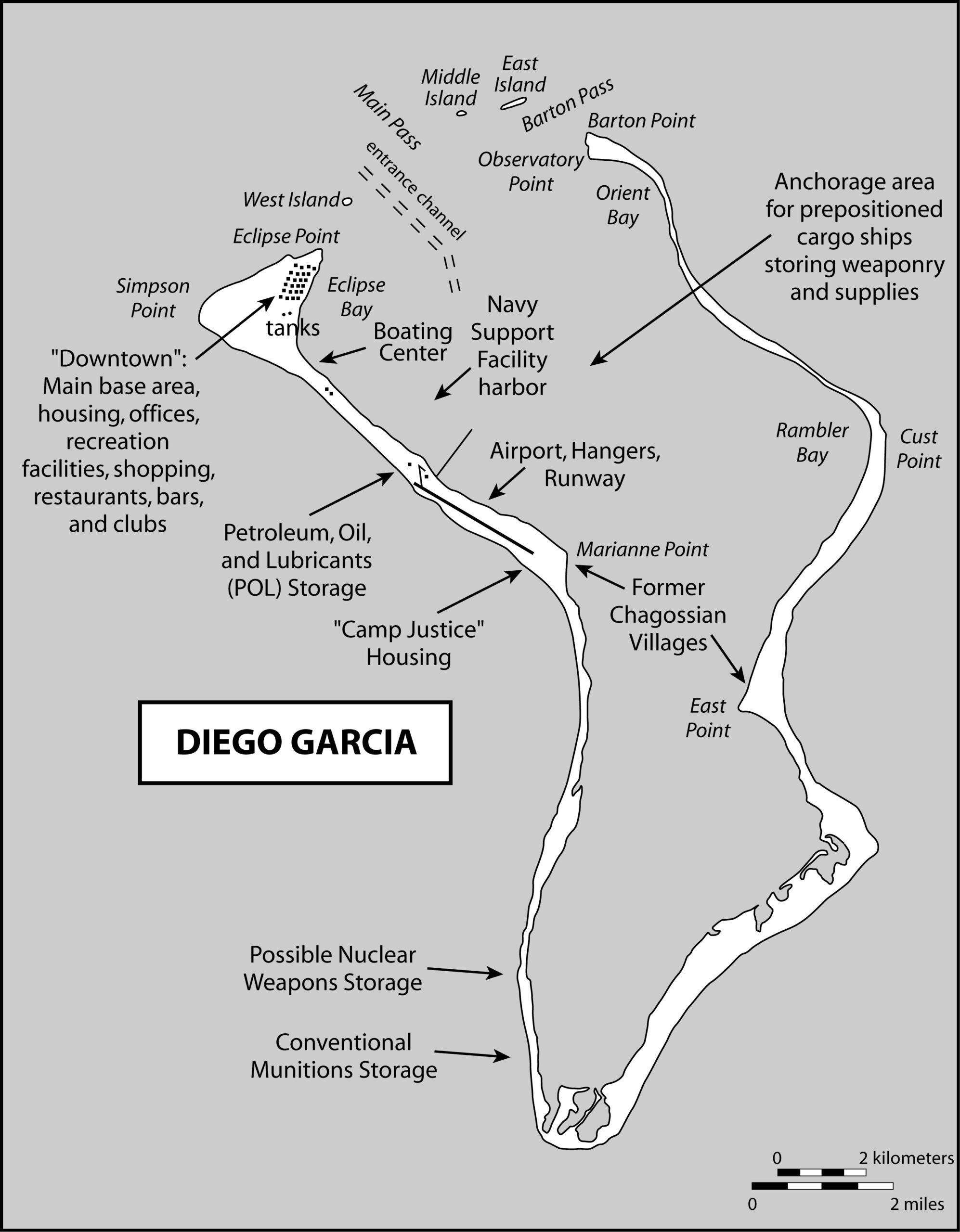

One of my principal concerns, from early in my 14 years as the civilian assistant director of the navy’s long-range objectives group (1956-1970), was attempting to assure the navy’s future ability to operate in the Western Pacific and Indian Oceans. I developed the concept that we ought to have a permanent USN facility in the WWII Majuro [Marshall Islands] pattern, i.e., a small atoll, minimally populated, with a good anchorage, on which we would build a simple patrol/logistic airstrip and some POL [petroleum, oil, and lubricants] storage.

It was sometime in 1958 that I first started giving thought to the Indian Ocean.While I had long been fascinated (from a distance) by small islands, and had since high school days been a collector of stamps used in the small island colonies, I had not paid much attention to Indian Ocean islands — but did remember, from the winter I had spent, at age 8, sick in bed with a cherished geography book, that there were numerous small British islands there.

Finding the time to collect and scan all the charts to see what useful islands there might be, and the relief to which, after running through many inferior sites, I found that beautiful atoll of Diego Garcia, right in the middle of the ocean.[In May 1960] I was the individual who proposed the detachment of these islands from Mauritius, the establishment of the British Indian Ocean Territory, and the construction of a minor navy logistic, patrol, and communication facility at Diego Garcia.

In 1960, when I proposed the establishment of a British Indian Ocean Territory and a minor US navy logistic base there, it would never have occurred to me that the supposedly civilized UK would take such a narrowly legalistic position. It is devoid of the slightest respect and compassion for the human beings of a native society which had evolved over nearly two centuries, formed by persons brought into the islands, originally as slaves, later as contract laborers, and then allowed, with many of their descendants born there, to remain after their employment. The moral tenor of the action is in the same ballpark as our internment of the Japanese, especially in the absence of an overriding reason. We were both irresponsible: We because it wasn’t necessary militarily, UK because as sovereign the civil responsibility is all theirs.

[The US] will justifiably be held guilty, as the most obvious beneficiary, of being an accessory and of evading responsibility or compassion. It is too late to undo most of the human damage. But perhaps it will help to allow and assist those evictees who still wish to return to at least the northern Chagos. It is my firm opinion that there was never any good reason for evicting residents from the Northern Chagos, 100 miles or more from Diego Garcia. Probably the natives could even have been safely allowed to remain on the east side of Diego Garcia atoll. It would be safe to let them go back, to North Chagos certainly.Correction of the wrongs as is still possible is not likely to require vast, costly efforts. Possibly someone in the new administration would consider it a worthwhile opportunity to improve the US image.

Such permission, for those who still want to return, together with resettlement assistance would go a long way to reduce our deserved opprobrium. Substantial additional compensation for [50-55] past years of misery for all evictees is certainly in order. Even if that were to cost $100,000 [$210,000 in today’s dollars] per family, we would be talking of a maximum of $40-50 million [$85-105 million], modest compared with our base investment there. Certainly, the climate for native rights has changed markedly since 1968-1973. And we have even made belated partial restitution for the Japanese internment.

I don’t know whether [you have] any interest in picking up this ball and running even a little way with it. Correction of the wrongs as is still possible is not likely to require vast, costly efforts. Possibly someone in the new administration would consider it a worthwhile opportunity to improve the US image. Having no entrée myself, and hoping you do, I pass the ball.

Postscript

In 2019 the International Court of Justice and UN General Assembly declared Mauritius to be the lawful sovereign of the Chagos islands. In late 2022, the British government began negotiations with Mauritius over sovereignty and the Chagossians’ right to return home.

To date, despite the people’s demands to participate, the United Kingdom has excluded Chagossians from the negotiations.

Stuart B. Barber’s letters can be found at www.chagosarchive.org.