With preoccupations large and small occupying the public mind, from the ongoing horrors in the Gaza Strip and the risk of a wider war in the Middle East to the never-ending saga of Taylor Swift, most Americans aren’t spending much time, if any, worrying about the risks of nuclear Armageddon.

But advocates of ending the nuclear danger are hopeful that a recent convergence of events might force the issue back into the public consciousness in a way it has not been since the anti-nuclear movement of the 1980s. Last month marks the 60th anniversary of “Dr. Strangelove,” Stanley Kubrick’s brilliant and darkly humorous satire of the cult of nuclear weapons. Christopher Nolan’s fictional portrait of atomic scientist Robert Oppenheimer is up for an Academy Award. Last month the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists maintained its “Doomsday Clock” — a measure of how close humanity stands to nuclear or environmental annihilation — at 90 seconds to midnight. And, on a more positive note, last month marked the third year in force for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, now ratified by 70 countries.

Arms control and disarmament groups are hoping to draw on these developments to sow the seeds of a new anti-nuclear movement. But what approach is most likely to get the public’s attention? Humor and satire as exemplified in “Dr. Strangelove”? Building on the visibility of “Oppenheimer” to highlight all the issues not fully addressed in the film, from the devastating impacts of the bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the deaths from radiation of victims of nuclear testing, uranium miners, and workers in the nuclear industry? Promoting hope for change based on the global progress of the nuclear ban treaty?

New Cold War Atmosphere

It will probably take all of the above and more to generate sufficient political power to reverse a runaway nuclear arms race that includes major new investments in world-ending weapons by the United States, Russia, and China. Efforts to do so will run up against a new Cold War atmosphere that seeks to delegitimize anti-war sentiments of all kinds and to smear peace advocates as pro-Putin, pro-China, pro-Hamas, pro-Iran or pro-[insert favorite adversary here].

So where do we go from here? One key element of the path forward is to take a (brief) pause to reflect on past successes in the fight to reduce nuclear risks.

The most common touchstones in thinking about the peak of anti-nuclear organizing are the 1982 million-person disarmament march in Central Park and the growth of the Nuclear Freeze Campaign, which played a pivotal role in transforming Ronald Reagan from the man who excoriated the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” and joked that “the bombing starts in five minutes” to the person who said “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought” and almost came to an agreement to eliminate nuclear weapons altogether in his 1986 summit with Mikhail Gorbachev at Reykjavik.

The Freeze campaign was not conducted in isolation. It drew inspiration from the European Nuclear Disarmament movement (END), a continent-wide effort sparked by plans to put short-range, nuclear-armed Pershing and cruise missiles in Europe, dangerously shortening the decision time for launching a nuclear conflict. And it built on past campaigns in the United States, such as the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, which led the charge that led to the end of above ground nuclear testing. As author and activist Vincent Intondi has demonstrated in his groundbreaking book on the topic, there has also been a strong thread of support for disarmament in the African-American community, from the first protests against the use of the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the anti-nuclear stances of Coretta Scott King (a key participant in the activities of Women Strike for Peace, whose activities are discussed below) and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. And the global movement of scientists against the bomb, exemplified by the Pugwash movement — founded in the mid-1950s at the urging of physicist Joseph Rotblat and philosopher Bertrand Russell — has been a foundation of nuclear disarmament efforts for six decades.

The growing 1980s movement against the bomb spilled over into the cultural realm as well, culminating in ABC’s historic airing of “The Day After,” a film that reached over 100 million Americans with a message about the dangers of nuclear weapons and the potentially devastating effects of a nuclear conflict.

A period of sharp reductions in nuclear arsenals followed the activism of the 1980s, with global arsenals shrinking from roughly 70,000 nuclear weapons in the mid-1980s to 12,500 now.

The administration of George H.W. Bush took tactical nuclear weapons off of US ships, the major nuclear powers commenced a moratorium on nuclear testing, and the US and former Soviet states collaborated in eliminating loose nuclear materials under the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction program. There were still enough nuclear weapons to end life as we know it, but things seemed to be moving in the right direction.

Barack Obama’s 2009 pledge in Prague to seek “the peace and security of a world free of nuclear weapons” was far from fulfilled, but the New START nuclear arms reduction between the US and Russia and the Iran nuclear deal at least held out hope of putting a lid on the nuclear arms race so that the fight for elimination of these deadly armaments could proceed.

But that was then, and this is now. The New START treaty — the last US-Russian nuclear arms agreement — hangs by a thread as enmity over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine casts a cloud over any prospect for US-Russian collaboration. The US and China have at least pledged to engage in dialogue over their relevant nuclear arsenals, even if actual agreements on nuclear control are not on the table.

What Will Motivate People?

So what is to be done? What motivated people then, and what will motivate them now?

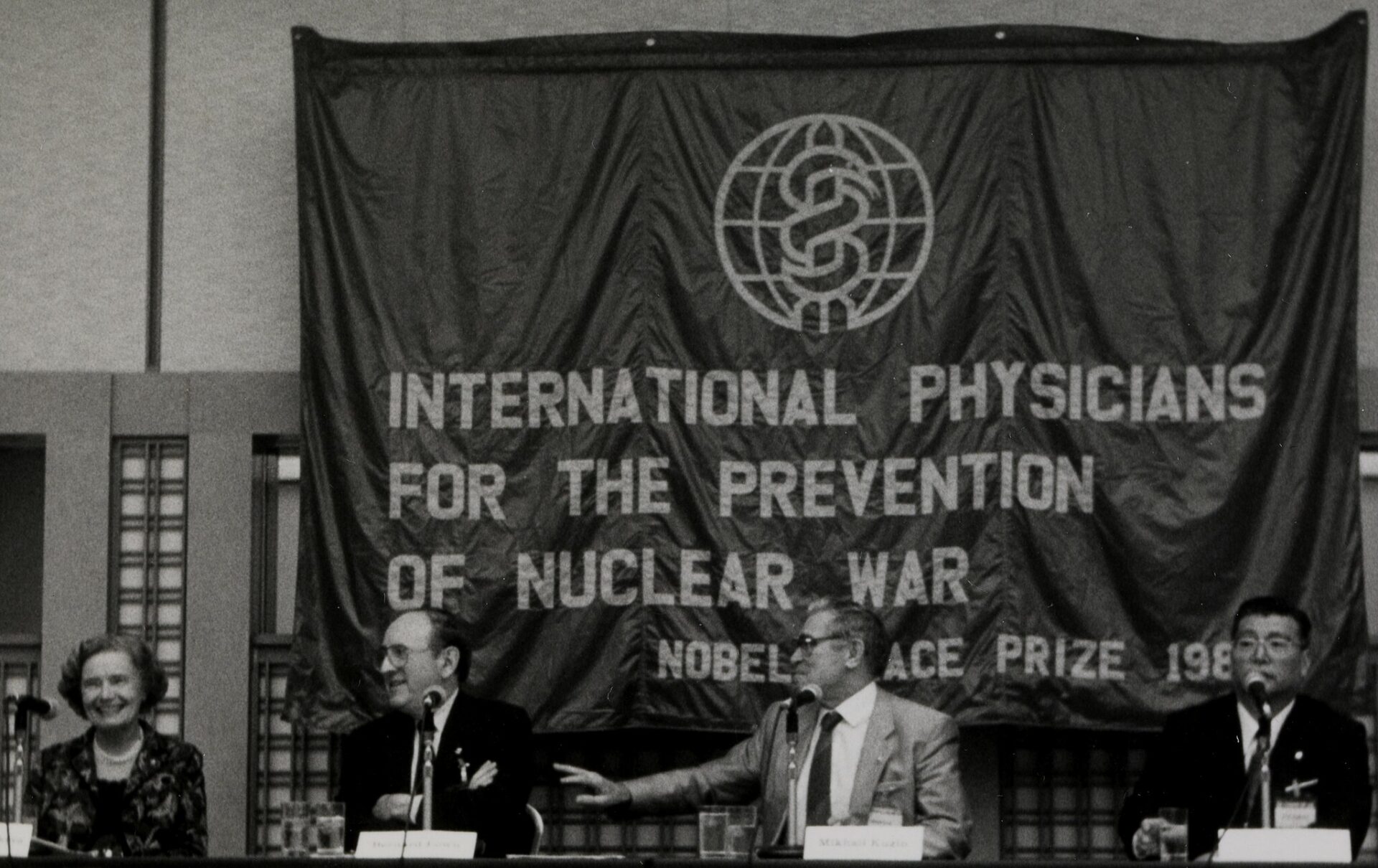

A perennial question in movement building of all sorts is the value of fear versus hope in moving people into action. The anti-nuclear campaigns of the 1980s drew on both. When Helen Caldicott and Physicians for Social Responsibility spread the word about the devastation caused by nuclear weapons, people paid attention. And Jonathan Schell’s brilliant, moving portrayal of our predicament in “The Fate of the Earth” reached people across the world. But in the United States this work paralleled the Freeze campaign, an initiative that gave people something to do about their fears, from promoting local political resolutions in hundreds of communities across the United States, to organizing groups by professional affiliation, to a lobbying on a bill in Congress that came within two votes of calling for a nuclear freeze.

A perennial question in movement building of all sorts is the value of fear versus hope in moving people into action.

None of this was lost on Ronald Reagan, whose aides warned him that the anti-nuclear movement had grown well beyond a small community of peace activists into the mainstream, and that he needed to come up with a program to assuage public fears. He took a two-pronged approach — the Star Wars program, which promoted the fantasy that technology could save us, and an arms control initiative that included genuine outreach to Russia. And his willingness to negotiate with Gorbachev was certainly impacted by the anti-nuclear movement, whether he chose to admit it or not.

Another key component of successful anti-nuclear organizing was creative protest. One clear example was the campaign by Women Strike for Peace to send baby teeth to members of Congress to underscore the frightening fact that Strontium-90 from nuclear testing was finding its way into breast milk and being transmitted to newborns. This action followed a November 1961 nationwide strike by 50,000 women who walked out of their homes or jobs, united under the slogans “End the Arms Race, Not the Human Race” and “Pure Milk, Not Poison.” And people sent 320,000 baby teeth to be tested for radiation in a study led by Louise Reed and Barry Commoner, thereby proving the radiation danger beyond a doubt.

Public Health and Safety

Now what? Some of the most promising organizing of the moment involves exposing the dangers that nuclear weapons pose to public health and safety whether or not they are launched. Campaigns to expand the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to cover all victims of US nuclear testing has bipartisan support in Congress and is within hailing distance of passage. The Marshall Islands has put the plight of the impacts of nuclear testing on their people on the international agenda. And the dangers of expanding production of plutonium triggers for nuclear weapons are receiving greater attention. Hopefully these efforts will open the door to a broader national conversation on the need to rein in the nuclear arms race and open a path towards eliminating these weapons once and for all.

The biggest challenge to progress on nuclear arms reductions may be the same one that faces all current movements for social change — convincing people that they can make a difference in a society where many feel that government is “rigged” in one direction or another, where disinformation and conspiracy cloud public judgment, and where racism, misogyny, and incipient fascist rhetoric and movements flood the public sphere, overwhelming and paralyzing people of good will and putting American democracy, imperfect as it is, at risk. The current moment calls for an all hands on deck movement to stand up for tolerance, diversity, racial and economic justice, and a truly responsive democracy. Anti-nuclear activism needs to be embedded in, not separate from, such a movement.

We need to go beyond incremental proposals to a full-throated demand for the kind of world we want the generations to come to inherit, a world worth preserving from the threats of nuclear annihilation, climate disaster, poverty, and war. This is not to suggest that any and all efforts to reduce nuclear dangers aren’t worth pursuing, but rather that smaller steps must be integrated into a larger agenda that can inspire grassroots action.

A new approach will mean coming together across political lines and communities like never before. Action to end nuclear dangers can and should be part of this movement, but ignoring other threats to people’s lives and livelihoods in favor of a single issue approach will not be sufficient. Some of these connections are already being made. They need to be intensified, first and foremost by building closer relationships through dialogue about perspectives and priorities among the full range of movements for positive change. In building this new movement, grim determination will not be enough. A sense of joy, of play, and a recognition of our common humanity must be allowed to flourish, both to sustain activism and to model the world we hope to build. Time is of the essence.