Seventy-five years after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a deadly war continues in the Pacific. In investigative journalist Jon Mitchell’s newly published book “Poisoning the Pacific: The US Military’s Secret Dumping of Plutonium, Chemical Weapons, and Agent Orange,” the author exposes decades of the careless mishandling of toxins and intentional misuse of power across the Asia-Pacific region.

Based in Japan, Mitchell is a well-known muckraker who has drawn on the extensive use of secret government and military documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and interviews with whistleblowers and military insiders to expose a culture of contamination in Japan, Vietnam, Micronesia, and remote US territorial islands.

But it’s in Japan’s southernmost Okinawa prefecture, home to more than 30 US military installations, where Mitchell shines a light on the deadly alphabet soup of toxic chemicals and substances that has been poured, dumped, buried, spilled, sprayed, hidden, scattered, and blasted into Okinawa’s air, water, and land, frequently with impunity or even public knowledge.

Everything from Sarin and VX agents and CS gas to waste oil, raw sewage, jet fuel, detergents, battery acid, coolants, DDT, PCB, PFOS, and PFOA have polluted the rivers, jungles, and coral reefs of Okinawa. Based on his reporting for the Okinawa Times and other newspapers, Mitchell details the deadly legacy of rainbow herbicides such as Agent Purple, Agent Pink, and the most infamous Agent Orange which the US used to denude the Vietnamese landscape as part of Operation Ranch Hand (1962-1970).

“Poisoning the Pacific” reads like a who’s who of bad judgment, institutional corruption and racism, negligence, deception, incompetence, and injustice. Mitchell brings to light the myriad ways in which the militarism that is said to “keep the peace” has, in fact, destroyed the earth, wreaking havoc on both the soldiers, sailors, and airmen of the US military and the local populations and Indigenous people across the rich and diverse Pacific region.

US soldiers inspect chemical weapons storage bunkers at Chibana Army Ammunition Depot, 1971. / Okinawa Prefectural Archives

Four chapters of this book examine Okinawa. What drew you to report so extensively on Okinawa?

Jon Mitchell: Okinawa has never been located in this context of American military contamination in the Pacific region. Everybody knows about Hiroshima. Everybody knows about Nagasaki. Most people know about Bikini and Marshall Islands but no one has ever put Okinawa within that context. During the Cold War, Okinawa possessed one of the largest stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction on the planet. Okinawa is such a tiny island but there were more than one thousand nuclear warheads there. There were 300,000 individual chemical weapons. The American military did biological weapons tests there and stored huge volumes of Agent Orange, so Okinawa has always been left out of American narratives of the Pacific. When you watch histories and read books about the Vietnam war, Okinawa either doesn’t appear at all, or it’s reduced to just one or two sentences.

When Americans think about the Vietnam war, they like to see it as a historical event, but on Okinawa the Vietnam war isn’t over.

I think it’s really surprising that Okinawa, as the American military said, was the key launchpad for the wars in Vietnam, and also Korea, and the Middle East, but American narratives always omit Okinawa. I think one reason is the ongoing military presence there.

In Okinawa today, there’s more than 30 military bases still there. When Americans think about the Vietnam war, they like to see it as a historical event, but on Okinawa the Vietnam war isn’t over. There’s still contamination. There’s still discrimination. The bases are still there. The proportion of US bases has been reduced on mainland Japan, but the burden has been pushed onto Okinawa. There are so many gaps in the public knowledge. That’s why I wanted to locate Okinawa within the context of the wider contamination and military cover up of environmental damage in the western Pacific.

For people unfamiliar with how Okinawa is different from Japan, what are a few key points?

Okinawa used to be the independent Ryukyu kingdom. It was a trading hub for the western Pacific… Okinawans are Indigenous people. They have their own culture, they have their own language. It’s very different from mainland Japan. Okinawa has always been seen as on the periphery of the Japanese homeland where they were expendable and so when it came to World War II, the Japanese government saw Okinawa as a place to delay the invasion of mainland Japan and maintain the imperial system a little bit longer.

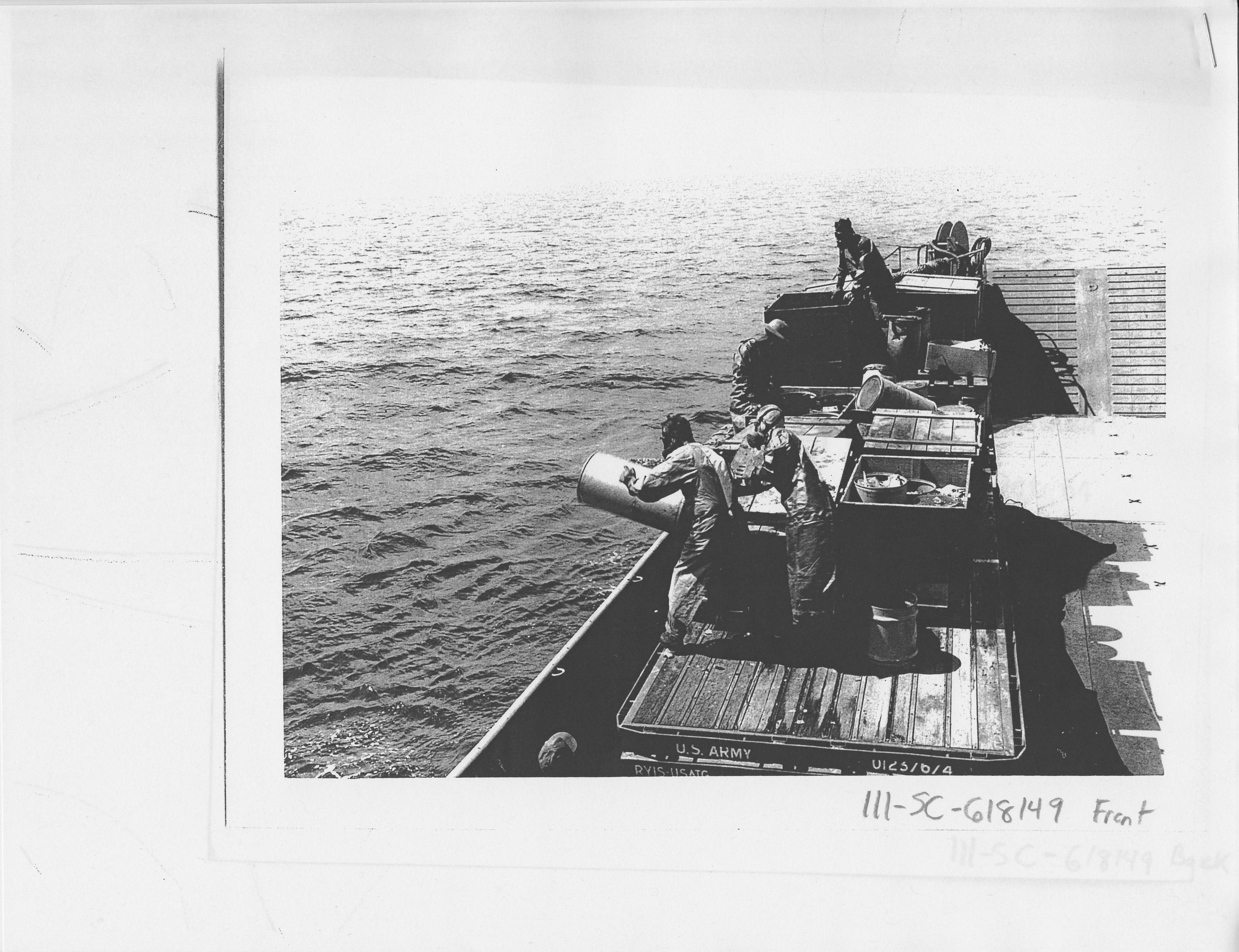

Men in gas masks, dumping unspecified chemical material into Okinawa’s sea from the back of a US Army truck aboard an Army boat, 1964. / US National Archives

Your book includes an extensive timeline (1947-2019) of environmental contamination and accidents on Okinawa. The scale, scope, frequency, range of locations, materials, and different victims is astounding. Did you ever just stop and say to yourself, “What is this?”

It’s a combination of incompetence from the military, particularly amongst the marine corps [which] is negligent in so many situations where they are very careless in handling dangerous substances. When you look at the use of depleted uranium (DU) on Torishima. When you look at the most recent leak of PFOS and PFOA at Marine Corps Air Station Futenma in April this year that was caused by a barbeque and the marines didn’t know how to shut off the sprinkler system so it leaked more than 100,000 liters of toxic chemicals off the base into a kindergarten and the local community.

Time and time again the American military in Okinawa has acted carelessly and negligently and their own service members and local Okinawans have been the ones to bear the burden.

A lot of that timeline is my original research that I have uncovered, during the past ten years using FOIA, interviewing whistleblowers, interviewing veterans. Until that timeline was published, nobody in Okinawa even realized the extent of the contamination and the diversity of the contamination, the range of chemicals, the areas where they were involved and just the sheer number of people who’ve been impacted.

What really hit me hard is the number of children who have been affected. You had arsenic poison from 1947, then going up to today where PFOS/PFOA is this firefighting chemical that affects children proportionally more than adults. This goes throughout the Pacific region. It’s often children who suffer the most because their bodies are smaller. If they take in a toxin, their bodies are still developing and it damages them from an early age.

When I put together that timeline, it did really blow me away — the sheer incompetence. One of the main threads is how often the military covers up contamination. It’s a throughline throughout the book from Hiroshima onwards. The American government has been lying about the environmental and human impact of hazardous chemicals and weapons of mass destruction in the Pacific region.

The US Army kept white rabbits at Chibana Army Ammunition Depot in an effort to monitor chemical weapons leaks, 1971. / Okinawa Prefectural Archives

In the Okinawa chapters you write about stunning examples of nuclear accidents and near misses, like a Nike nuclear missile that was fired into the sea and the loss of a one megaton hydrogen bomb.

It’s appalling. Everyone knows about Greenland where there was the accident with the hydrogen bombs. People know about lost bombs in Spain, North Carolina had a “broken arrow” as well. But Okinawa is left out of these narratives. One of the most telling cases is not nuclear but Project 112 — biological, chemical secret tests on military members held throughout the Cold War. The VA and the Department of Defense have a list of locations where Project 112 operations took place and Okinawa doesn’t appear on it. Even though I have the documents via FOIA from the American military proving that Okinawa was a Project 112 site, the American government still doesn’t include it on that list. As a result, the veterans who were exposed are not eligible for automatic VA coverage if they were sickened by those tests.

So you always see this case of Okinawa being left out by the military off all these lists whether it’s Agent Orange, whether it’s nuclear accidents, whether it’s Project 112. Okinawa has always been omitted by the Department of Defense and the VA. As a result, not only Okinawans suffer but also American veterans equally suffer.

Under US occupation, American military bases on Okinawa possessed an arsenal of more than one thousand nuclear weapons. Here US Army technicians conduct maintenance on a Mace missile capable of carrying a one-megaton warhead, 1962. / US National Archives

What can people elsewhere learn from how Okinawans deal with these issues?

Due to the experiences of the Battle of Okinawa, where they were betrayed by the military and more than a quarter of the civilian population died, Okinawans have a real understanding of the dangers of militarism, and of course actual war. Ever since the end of World War II, Okinawans have had a very strong Pacifist spirit, and they’ve been aggressively fighting for peace in their island and the region.

Throughout the American occupation of Okinawa — 1945 to 1972 — there were massive demonstrations against the military and a lot of these demonstrations were against weapons of mass destruction. After the leak of nerve agent on the island in 1969 there were huge, huge rallies against the military.

Also, unlike mainland Japan, Okinawan politicians and leaders tend to be on the side of the people rather than the side of the elite. When you look at mainland leaders from the LDP (Japan’s dominant Liberal Democratic Party), they’re usually characterized by corruption, nepotism, and a sense of elitism over regular folk. But on Okinawa, the governors and elected officials in general, tend to put the rights and the health of their own constituents, their own local people, over the rights of big business and the military.

Going back to your question about lessons, I think this is not only an American military problem. This is a military problem. Militaries all around the globe are dirty businesses where they create massive amounts of waste and contamination and sicken their own service members and most significantly they sicken the lives of Indigenous people.

Throughout the world, the superpowers have always tested their weapons of mass destruction in their colonies. Whether it’s China testing weapons in Uyghur communities, they suffer fallout. Whether it’s British military testing nuclear weapons that contaminated Aborigines in Australia, whether it’s Marshallese contaminated by American nuclear tests, it’s always the Indigenous communities who suffer the most and that is Okinawa… After that, the experience of World War II showed that militarism is not the way to go and that peace is the most important thing for the region.

Okinawa officials visit a dumpsite of surplus US herbicides in southern Okinawa, 1971. / Okinawa Prefectural Archives

Given that politicians and the military are unlikely to change quickly, how can ordinary people effect positive change? For people who see the injustice in all of this, what should they be doing?

Number one, I think this change will come from within the military community themselves. Active [duty military personnel] and veterans are really, really important. They can write to their elected officials and demand that bases in Japan [are in] environmental compliance and environmental checks are conducted to protect the lives of both the service members and their families, and the local communities.

Number two, you’ve got to look at American policymakers who see China as a threat but at the same time, their own environmental problems are undermining the military presence. If they are going to keep contaminating this region, then it will undermine their argument that bases are there to protect people. You can’t protect people without protecting the environment.

Okinawans staged a demonstration calling for the removal of chemical weapons from their island and for an end to the US bombing of Cambodia, 1970. / Okinawa Prefectural Archives

What’s your takeaway message regarding poisoning the Pacific as it relates to Okinawa?

The headline issues are nuclear, chemical weapons, VX gas, but the other chemicals that have been contaminating Okinawa cause many, many problems too and today Okinawa is suffering more than any time in its history. It’s half a million people whose drinking water is contaminated by Kadena Air Base, the largest airbase in the Pacific region. And the military isn’t allowing local authorities to go onto the bases and check. It’s just awful. The military needs to come clean and admit what has happened and it needs to help the local communities overcome this problem.

The contamination in Okinawa needs to be seen in the wider oppression of Indigenous peoples and the wider struggle for environmental justice. The contamination has hit Indigenous peoples more than the so-called homelands of the mainland United and mainland Japan and so people need to see it in that context. The struggle for environmental justice is tied up in the struggle for Indigenous people’s rights because they have always borne the burden of militarism and by default military contamination.

Jon Letman is a Hawaii-based independent journalist covering people, politics, and the environment in the Asia-Pacific region.

Jon Mitchell’s comments were edited for length.