“I told them that we did not regard [the atomic bomb] as a new weapon merely but as a revolutionary change in the relations of man to the universe and that we wanted to take advantage of this; that the project might even mean the doom of civilization or it might mean the perfection of civilization; that it might be a Frankenstein which would eat us up or it might be a project ‘by which the peace of the world would be helped in becoming secure.’”

- Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s Diary entry on May 31, 1945

Today, nuclear deterrence seems almost an inevitability of international relations. After the Trinity test in 1945 and the Soviet atomic test in 1949, unilateral disarmament seemed impossible as a Cold War arms-race dynamic ensued. However, the scientists of the Manhattan Project foresaw the certainty of such an arms race and envisioned more and more destructive atomic weaponry.

Rather than advocating a theory of deterrence, those closest to the creation of the bomb articulated a radical alternative to living with the security dilemma of nuclear-armed states. Even before Trinity, a scientific movement had begun for world government control over nuclear energy. It was envisioned as a type of world federalism whereby the only possessor of nuclear weapons would be the world state entity. Today, such a concept seems far-fetched, yet it appeared as an absolute necessity in the aftermath of two world wars, the founding of the UN, and the creation of the most destructive weapon in history.

Rethinking nuclear deterrence requires conceptualizing alternative futures rather than the possibility of a failure of nuclear deterrence, accidental launch, or intentional use. Re-examining the scientists’ movement, despite its perceived failure, reveals the contingencies of deterrence and the possibility of a very different post-nuclear world. The early nuclear-era solutions offered by scientists and even policymakers might inform new directions today. To imagine that deterrence will never fail confines leaders and policymakers to outdated solutions in a rapidly changing world. With President Vladimir Putin weaponizing nuclear risk to wage a war of aggression against Ukraine, China expanding its minimum deterrence posture, and the United States prioritizing nuclear modernization, can we continue to rely on the Cold War deterrence model?

The national security state of the Cold War and Red Scare pushed aside reasonable scientific assessments and activism in the early nuclear era. Instead of the peaceful use of nuclear energy and disarmament, the Cold War beckoned an unprecedented arms race and a culture of secrecy rather than cooperation and exchange that the scientists advocated. Ultimately, the calls for world government to control nuclear weaponry seem further today than in 1945 and are clearly no longer a feasible solution. Nevertheless, if we are to rethink deterrence in the age of a multipolar world, we need to see the possible alternative paths not taken by those closest to the creation of the bomb. Our goal is to inspire a conversation versed in the rich historical record of the Manhattan Project to propose novel ideas for possible future worlds today that minimize the risks of nuclear use by welcoming the revival of scientific activism and thought into the policy-making process.

World Government

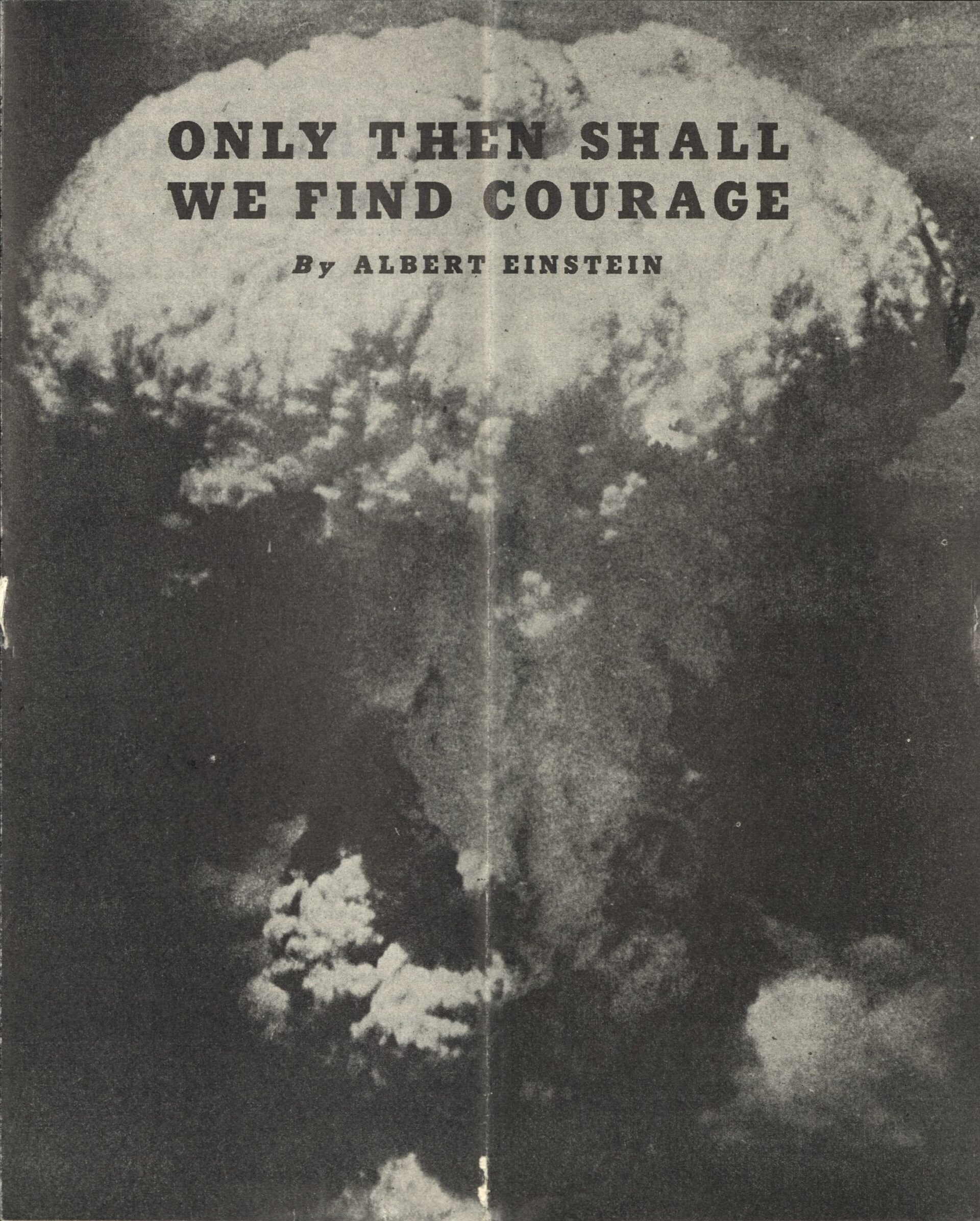

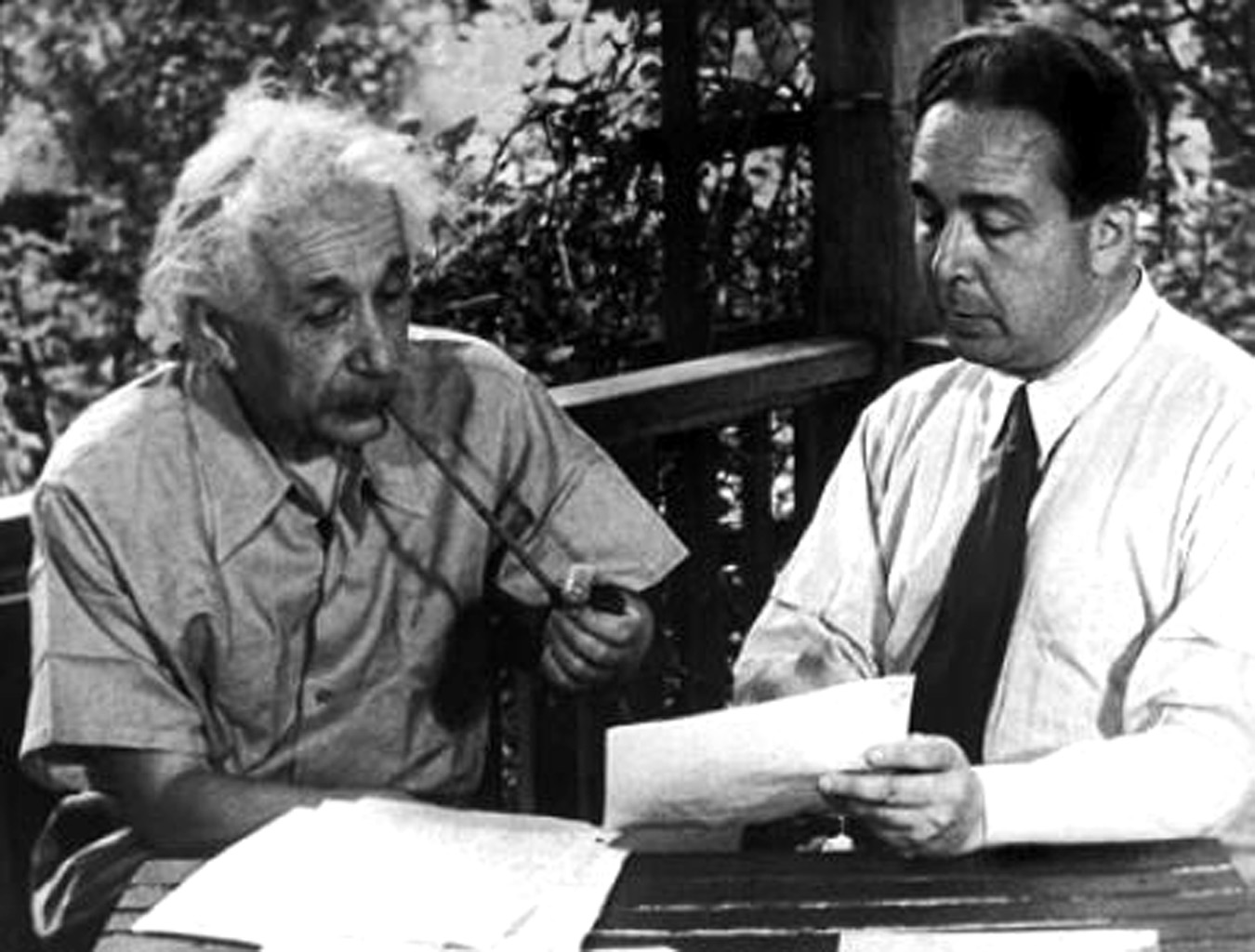

“One World or None” represented the leading conviction of scientists, journalists, and politicians regarding the new world created by the atomic bomb. The top nuclear scientists — with about half of the essays written by Nobel Laureates — urgently promoted this message through a series of essays. Notable contributions include J. Robert Oppenheimer, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, and Leo Szilard. Nuclear one worldism represented a theory of state-building fit for the nuclear age, in which the security crisis would be solved by forming what political scientist Daniel Deudney termed an omnistate that would control the world’s nuclear energy.

Recognizing the immense political, moral, and catastrophic consequences of the nuclear bomb, scientists sought to influence the government and the public on the necessity of international cooperation on atomic issues. Many scientists saw scientific internationalism as foundational for creating an international authority for atomic energy control. Scientific internationalism was described by the Editor of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Eugene Rabinowitch, as a “set of ecumenical traditions” that scientists adhered to by recognizing the universal value of science and the need for unrestricted scientific exchange across nations. Scientific internationalism would be a foundation of world government by enhancing trust and collaboration across countries.

While not all the scientists who worked on the atomic bomb might have believed in international control, many of them seriously considered the political implications of their work, allowing scientists to exert influence on the highest echelons of policy briefly.

Because many scientists believed in the importance of international contact as the basis for peace and security, they often felt an ethical and political responsibility to promote global atomic control. For example, as expressed in the 1944 Jeffries Report — an outline of the implications of nuclear energy completed by Manhattan Project physicists like Enrico Fermi, Arthur Compton, and James Franck — scientists felt that they had a “moral responsibility” to “enlighten public opinion” and to “strive for the establishment of efficient international supervision over all aspects of [nuclear energy].”

Letters on World Government

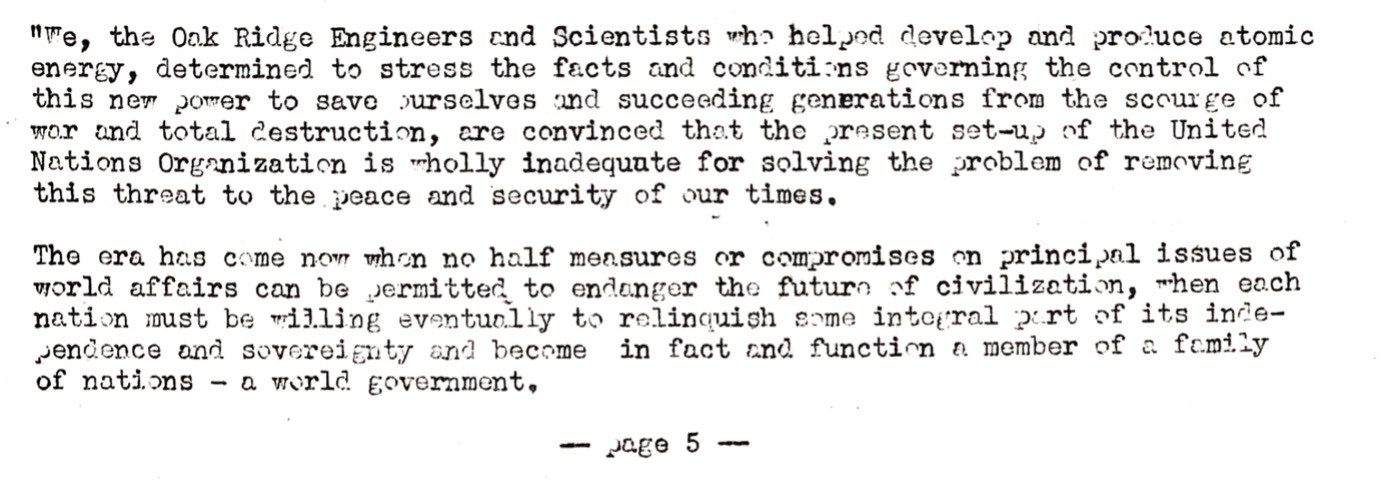

Scientists at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, took a particular interest in the development of a world federal government as a solution to the inevitability of nuclear proliferation and its potential to hold the world hostage. Based on extensive archival data at the University of Chicago Library in the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, we present the origins of this radical idea. A group of four Oak Ridge scientists — John L. Balderston, Jr., Dieter M. Gruen, W.J. McLean, and David B. Wehmeyer — undertook the “Letters on World Government” project as representatives of the Atomic Oak Ridge Scientists (AORS) and the Oak Ridge Engineers and Scientists (ORES). The group wrote to 154 primarily American and British leaders in science, culture, and politics, soliciting their opinions and advice about establishing a world government. Over the next year, as they received more than 100 responses to the letter, the committee compiled a final report in 1947.

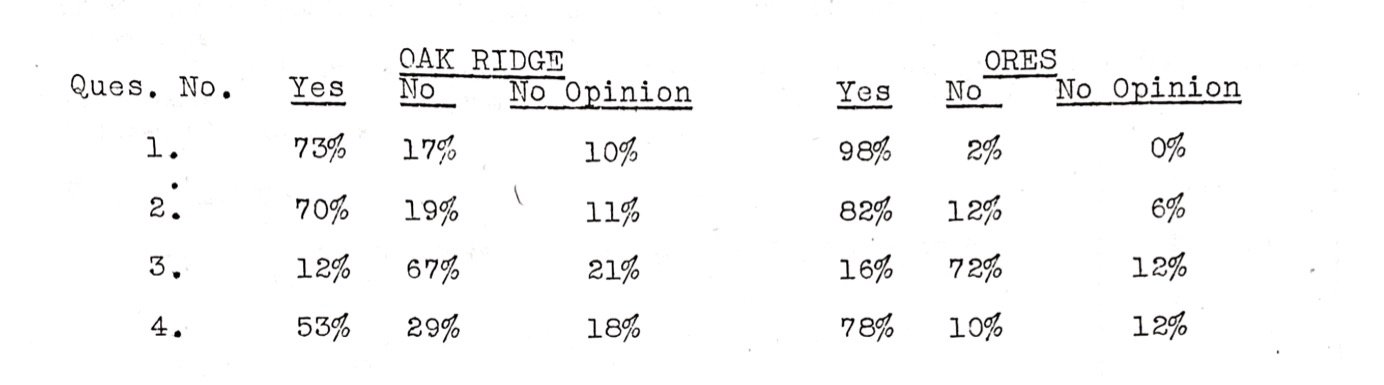

On November 13, 1945, the editorial committee of the Atomic Scientists at Clinton Laboratories, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, issued the following statement:

“Atomic power can make life immensely better, but it can also destroy it entirely…We have been convinced that the atomic bomb must be controlled…We cannot tolerate another war…Not only will nations have these bombs, but there is no defense against them…There has to be international control with teeth in it and placed above the sovereignty of nations…Only with world wide [sic] control can we look forward to a lasting era of peace.”

In their solicitation letter, Balderston et al. recognized that with nuclear weapons, “another war could mean the destruction of present civilization, [and] we are trying to learn how war can be prevented.” Their solution moved beyond the UN Organization (known as UNO at the time) toward a world government to prevent atomic destruction. They concluded that “lasting peace cannot be achieved by any system of confederation but only by a world government” and thus “all nations must turn over to it all of their external sovereignty, including power to declare war and keep armies…”

They recognized the inherent difficulties, including the unwillingness of states to give up sovereignty. Nevertheless, they solicited opinions on whether world government should be established immediately (as early as November 1945) or continue with the UNO confederation with an eventual gradual move toward world government. Ultimately, they viewed it necessary for “this world government to be set up soon if another war is to be averted.” However, disagreements/concerns/dissension between scientists emerged because of differing opinions on the political structure of international authority. The AORS and the ORES became frustrated with the emerging UNO structure and believed that the veto power of the UN Charter “must be replaced by a system of world law from which no state is exempt.”

One of their proposed resolutions to be voted on by members at ORES clearly stated their position: