In facing the Russia-Ukraine War, several European countries have increased their military spending and their weapons supplies to Ukraine. Germany stood out when the country announced a plan to prioritize military spending through a special fund to equip the Bundeswehr, the German armed forces.

The media has portrayed this as a dramatic U-turn and a historic shift in military aid policy. And German Chancellor Olaf Scholz referred to it as a Zeitenwende: a “turning point.” Although Berlin’s commitment to go over the 2% economic output in NATO is highly relevant because this move will catapult Germany to being one of the top largest military spenders, the delivery of military equipment to conflict zones like Ukraine needs to be further analyzed. Is it as unprecedented as it has been presented? Furthermore, Germany is currently the world’s fifth-largest arms exporter, and a January 2022 report showed that arms sales to Egypt boosted its weapons exports to record levels in 2021. So why is selling arms to Ukraine considered an about-face?

THE LEGACY OF WORLD WAR II

Germany has a huge arms industry and consequently exports its military equipment to many different countries. While not every arms sale is problematic, the criticism is directed toward the fact that core recipients of these weapons included crisis regions, human rights abusing states, war waging states, and dictatorships. From the use of German weapons by the Burmese army to shoot demonstrators in 1988, to equipping local militias in Yemen, to multiple conflicts involving Egypt, to the use of German weapons by the Bahraini government against the democracy movement in 2009, to arming of Apartheid Israel, and supplying of Kurdish forces in Iraq, the German government has constantly supplied weapons that effectively violate arms exports policy criteria.

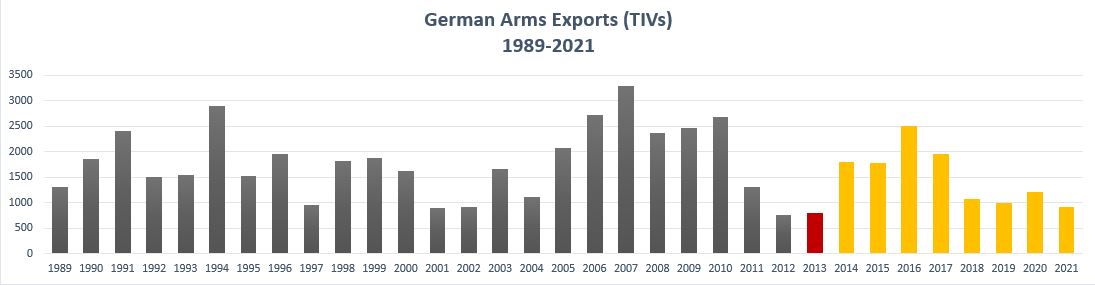

Source: SIPRI Database

Yet, Berlin has successfully managed to position the country as a civilian power committed to human rights. This long-standing reputation of restraint dates to World War II, and it is a well-trod story in German public discourse. Yet, the story is limited at best. A closer look at history shows double standards and a continual expansion of German arms sales.

After WWII, Germany sought to have a broad military restriction policy that led to conciliation, rehabilitation, predictability, and trust. The development of its military industry and its weapon strategy was motivated by domestic needs to achieve economic prosperity and self-defense. However, the process was slow due to prohibitions set in place by both the Allied Control Council and NATO, which only began to disappear by the end of the 1950s.

Mounting Soviet pressure and a non-unified response by the West in subsequent years alarmed Germany, and the government decided to create the War Weapons Control Act (Kriegswaffenkontrollgesetz), which would become the legal base for its arms exports. The fundamental aspect was to deny licenses in case there was a risk that the weapons could be used to the detriment of peace, particularly for an act of war. This showed an open position by Germany towards its own arms exports and its receiving countries.

At the time, the United States began to experience a decrease in its influence due to a balance of payments deficit, its growing engagement in Vietnam, and the decrease of American troops in German territory. This pushed Europeans to assume a progressively larger contribution of their own defense. In this context, Berlin established the first national guidelines to complement the War Weapons Control Act in 1966. They indicated that preferred arms destinations were NATO and EU members, while they would avoid selling weapons to tense areas. Nevertheless, Germany decided to increase arms exports, which skyrocketed due to three main factors: The Bundeswehr was completely armed and there was a saturated domestic market for weapons, the recession ended in 1968, and there was a stable exchange rate with a significant growth in German general exports. The favorable economic scenario, weapon technology development, and international geostrategic changes encouraged a modernization of weapon systems, usually through multinational collaboration.

In the next decade, the German defense industry was developed to achieve important economic and political objectives, such as the further integration into NATO, the control of Western Germany’s arms industry, European unification, political legitimacy, economic development, the strengthening of European manufacturing of high tech devices in relation to the United States, and the promotion of national security. The armament strategy was directed to achieve many of these goals. The second national guideline was also established, indicating weapons should not be exported to conflict regions and stressing the consideration of negative security consequences for Germany from potential arms transfers to third countries. Western Germany sought to prohibit arms transfers to “tension areas” and to allow exports to non-NATO members under specific circumstances. However, the decision was taken by the cabinet and did not adopt a law or regulation character. For example, Berlin violated the arms embargo to South Africa in 1977 and continued to send weapons to Johannesburg until 1992.

The third guideline, established in 1982, stated transfers were to be prevented in the case of certain local conditions of the receiving country, recognizing exceptions if German vital interests were affected. Despite these restrictions, the arms industry grew. In 1984 Germany had the first maximum trend-indicator values (TIVs) — a unit that measures trends in the flow of arms over time — showing real growth in its arms industry. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute database shows German arms transfers grew 51.22% from 1979 to 1984, amid continual growth over the years.

After the country’s reunification in 1990, Germany’s foreign policy embraced military limitations favoring institutional and cultural contexts for European integration and relations with the US. Germany also sought to play a more active role in international politics, which became a key component of its decision-making process. For example, NATO pressured Berlin to increase its contribution to multilateral missions leading to the first combat mission in Kosovo in 1998. That same year, the EU implemented the Code of Conduct on Arms Exports, which covered issues such as human rights violations in receiving countries. The human rights clause was included for the first time in German norms.

The political principles of January 2000 articulate Germany’s “responsible and restrictive licensing policy,” and commitment to human rights, and states: “In contrast to the practice in a number of other countries, Germany does not treat arms exports as an instrument of foreign policy.” At the time, Berlin exhibited a weak foreign security strategy, which could be seen in its opposition to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 while participating in the Afghan war. Nevertheless, Germany tried to strengthen its position toward human rights and established the fourth guideline, which made respect for human rights a fundamental characteristic to ensure weapons transfers. In 2008, the Code of Conduct on Arms Exports was substituted with EU Common Position 2008/944/CFSP which defined the common rules for exports of military technology and equipment when deciding whether to approve conventional arms transfers.

The landmark UN Arms Trade Treaty — the first legally binding international treaty on arms sales — was signed in 2013 and entered into force in 2014. The treaty meant a significant change in arms exports. It regulates the international trade in conventional arms by establishing international standards: The adoption of basic regulations and approval processes, the establishment of a national control system, the prohibition of authorizations if there is a risk the weapons will be wrongly used or pose a threat to peace and security, the establishment of diversion prevention measures, and the submission of annual reports.

Germany signed the treaty the day it opened for signatures, and proudly declares so on the website of the Federal Foreign Office. It was a hopeful step for arms monitors, given that Germany had been lacking transparency in previous years.

Despite German politicians’ criticism of Arab states’ increasing military interventions and support of armed militias, arms exports to Arab countries have remained high since 2011.

On paper, the development of such policies has worked to sustain the narrative of a responsible civilian power. However, this was about to experience a quiet but conspicuous and noteworthy intention to change.

GERMANY’S LEGITIMATION STRATEGY

During the 49th Munich Security Conference, the Federal Minister of Defense, Thomas de Maizière, began hinting at a shift in policy. While still protecting human rights, he expressed discontent toward the way these were approached. He stressed that human rights require the participation of other agents to design efficient strategies. He considered that while the responsibility is persistently resting on foreign states, local states are not assuming the appropriate role to secure themselves. This speech set the precedent to legitimize a change in foreign policy. And in the 2013 Military Equipment Export Report, the former Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy, Sigmar Gabriel, stated that those affected by war should be able to acquire the means to ensure their own security. It was set as an international necessity and a goal for Berlin.

The following year, at the 2014 Munich Security Conference, former German Federal President, Joachim Gauck argued that security, peace, prosperity, free trade and human rights should be considered together. As such, all trade was promoted, including weapons, as part of security and peace. He identified threats to the European order and argued that Germany should assume a stronger position to sustain the international order. The speech closely followed the position of 2013. He also favored military alliances and supported the arms trade among its partners. Ursula von der Leyen, then Defense Minister, also expressed the obligation and responsibility to contribute to modest progress towards the possible solution of current crises and conflicts.

In 2015, the provision of weapons to Iraq showed that Germany was convinced that sending weapons and German troops was a legitimate and adequate response to the conflict. During that year’s Munich Security Conference, von der Leyen declared that the country had broken some taboos. Besides humanitarian aid, they provided the Pashmerga (the Kurdish branch of the Iraqi armed forces) with weapons and ammunition. If anything, this showed a significant change in policy. Von der Leyen also brought forward what she calls “leadership from the center.” This type of leadership meant having the will and ability to act. A report from December 2015 by the French Institute of International Relations showed that Germany was moving toward a greater contribution to international security. However, it was still unclear how. What we do know is that since that year, Germany has granted licenses to the Saudi-led coalition that amount to over 5.2 billion Euros.

In 2016, former Chancellor Merkel expressed that Germany and Europe should make a larger commitment to security and peace. Once again, von der Leyen expressed Germany’s push for a larger role in its armed forces and military intervention. The Bundeswehr became an important element for German leadership from the center. That year continued to experience steady growth in German arms exports that has since been sustained.

ARMING UKRAINE

How is this relevant for today’s scenario? In the face of the Russian invasion, Western governments are flooding Ukraine with weapons. Germany was reluctant to do so and as recently as February, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock evoked the country’s destructive history to justify decisions not to send arms to Ukraine — a position that a majority of Germans supported at the time. Germany is now sending various arms, and a few weeks ago it decided to procure additional weaponry worth 300 million Euros. Berlin was breaking some of the same taboos von der Leyen declared to have broken back in 2015.

These choices are narrated as a “sudden” change in policy, but this story requires further scrutiny. The persistent depiction of Germany as peaceful and responsible has prevented criticism over the years. The myth of a restrained weapons policy provides support and ease in the West. Meanwhile, German discourses at high-profile security conferences helped legitimize its arms exports and support the mythology of a self-contained Germany.

The so-called U-turn is not a partisan decision; the shifts have been mounting since Merkel’s administration and continue under Scholz. Despite German politicians’ criticism of Arab states’ increasing military interventions and support of armed militias, arms exports to Arab countries have remained high since 2011. In 2020, Germany approved over 1 billion Euros in weapons to countries involved in the Yemen and Libya conflicts. A 2021 report by the Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy and the German Section of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom expressed concern over the fact that authorized German arms exports repeatedly violate international law and that the refusal to implement a sufficiently restrictive arms exports policy contributes to international militarization. During the former Chancellor’s last days in office, with Scholz as finance minister, arms exports hit a new record with a last-minute approval of 5 billion Euros. Exports included countries like Egypt which had been under criticism for its human rights violations and involvement in conflicts. This begs the question, is it really an about-face we are seeing? Given the evidence and the history, the answer is undoubtedly no. However, Germany’s narrative of restraint has been carefully packaged and is maintained in the story of this moment well enough to allow us to see it as a “historic shift.”

Although the export of weapons to some troublesome third countries has become the rule rather than the exception, what is different in Ukraine is that there is currently public and governmental pressure and support for arming Volodymyr Zelensky’s government. The identification of European and Western governments with Ukrainians is exhibited in media reports that have been labeled as racist and the wholehearted welcoming of Ukrainian refugees in Europe. This highly contrasts other conflicts where there are neither empathic media portrayals nor citizen support for weapon deliveries. From this perspective, German weapon exports announcements are indeed different. They are open and visible because German and Western constituents support them. Arms exports to other countries are carried out more quietly. This is problematic because it can lead Germany — already a major weapon exporter — to be less cautious than before in pursuing weapon sales to countries with questionable human rights records or to armed conflict areas.

Furthermore, in the rush to supply Ukraine with arms, Germany is not alone in skipping arms transfers criteria. The necessary measures to assess risk and prevent diversion established in the Arms Trade Treaty are not being followed by countries eager to send arms. The quantity of weapons sent to Ukraine may contribute to an enduring ecosystem of insecurity and heighten the risk of diversion. Furthermore, Ukraine has a high level of corruption that should not be overlooked. However, the sentiment across Europe is a rise in support for direct military aid to Ukraine and an unfortunate decrease in support for diplomacy. Along with the discourses to increase military assistance and direct involvement in armed conflicts, the conflict in Eastern Europe has provided Germany with the perfect excuse to increase their weapon exports despite their national law and their adhesion to the ATT. The sum of these factors may well create unintended problems for Ukraine and the region in the coming years.

Gabriel Mondragón Toledo is a PhD student at the University of Hamburg, Germany, studying the role of narratives in practices of disarmament and arms control. He is also a member of the Center for Sustainable Society Research from the University of Hamburg.