On the morning of Oct. 20, I found Mohammad Aslam standing at the front of a crowd that had gathered to march in Sepolia, a working-class suburb in Athens. Everyone had come out to voice their anger over a recent rash of far-right attacks, including an assault that sent Aslam to the hospital. Aslam was helping others hold up a banner, and now and then, someone would come up to let him know they supported him. More demonstrators trickled in around him, greeting one another and chatting. A bus parked down the street, and out filed columns of riot police, helmets on and thick plastic shields in hand. Some of the protesters had placards lashed to their backpacks. “No to war,” read one, adding: “Open the borders.”

Anti-racist groups and migrant rights advocates had called the march. The Sunday before, a group of local men stormed a facility that houses refugee youth in the neighborhood after a brief scuffle between two boys who reside there. The men busted down the building’s front door, smashed out windows, and injured two young boys. Among the mob, a witness later told local press, was at least one well-known member of a far-right outfit.

A day before the Sepolia incident, on Oct. 12, Aslam had joined hundreds of Pakistani delivery drivers and protesters as they marched through the city center to protest the death of a Pakistani man in an Athens police station nearly a month earlier. After the march ended, the crowd broke apart and Aslam went to look for an ATM. As he pulled his motorbike up to an intersection, a car almost slammed into him. He looked up at the driver. “I’m sorry,” he said, “but you have a stop sign.”

“What are you, a smartass?” the driver shouted. “Get out of here, you dirty Pakistani.”

Aslam brushed it off, then continued on his way, got money out of the ATM, and prepared to head out, putting on his motorcycle helmet. He was on a video call with his wife when he realized he’d lost his necklace. He noticed three men were following him but took his motorbike back to the square to look for the chain. Almost as soon as he got there, he said, the trio swarmed him. They yanked off his helmet, and the blows crashed into his face and skull, some with brass knuckles. Blood poured from his face down onto his clothes. “Go back to your country, you filthy Pakistani,” they shouted. “What do you think you’re doing here?”

Standing in front of the rally in Sepolia a week later, he told me the story through broken teeth — the assault had cracked three of his incisors — and pointed to the stitched-up gashes on his chin, beneath his right eye, and on his skull. It took the doctor 10 stitches to stop the bleeding, he explained, and he spent a day at the hospital before he could go home. As a Pakistani in Greece, he had experienced racism during his 18 years in Athens, sure, but despite a handful of close calls, no one had ever assaulted him.

He was already having a difficult time before the attack, but the incident made things worse. His mother had passed away a little more than a month earlier back in Pakistan, and although he paid his taxes and was in the country legally, the Greek government had recently rejected his application to bring his wife to live with him in Athens. Because the renewal of his own residency papers was still pending, he had to attend his mother’s funeral by video call.

He liked to post comedic videos on his TikTok — he has a large following of nearly 51,000 — but he spent most of his time working as a food delivery driver. He said he never bothered anyone. Now, he couldn’t stop wondering why anyone would subject him to such violence. “My only hobby is working,” he said. “Working, working, working.”

“I’ve been very scared.” – Mohammad Aslam

I asked him whether the incident had changed the way he went about his life, and he said he had spent the last week either at work or at home. “I’ve been very scared,” he admitted. “I haven’t gone out at all. They had to call me 100 times to get me to come here today.”

By the time he finished the story, a few hundred people had arrived in the square. Activists and advocates took turns on a bullhorn, calling on the crowd to send a message that the far right wasn’t welcome in Sepolia. When Aslam’s turn came, he thanked the crowd several times for supporting him and explained that migrants in Greece needed help. The demonstrators then set off through the tight streets that weave between Sepolia’s densely packed apartment blocks. “In our neighborhood,” a banner in the front row said, “there is no room for racists and fascists.” Bobbing above the march were red flags and yellow placards with an image of a fist crashing through a swastika. Locals crept out onto their balconies, some snapping photos on their phones and others applauding in solidarity. “We live together, we work together,” the marchers chanted at once, “locals and migrants, crush the fascists.”

“Treating Us Like Animals”

Anti-migrant violence is nothing new in Greece. Of the nearly 1,200 hate crimes the Racist Violence Recording Network (RVRN) watchdog documented in Greece between 2012 and 2020, more than half targeted refugees and migrants or humanitarians who worked with them.

In early November, I met a Bangladeshi man named Sheikh Gias at a café in Exarchia, a central Athenian neighborhood long known as a hub for refugee solidarity and left-wing politics. He sipped hot tea and explained that, at 36 years old, he had spent his entire adult life in the country. He worked an under-the-table job as a chef for many years, and although he obtained legal papers several years ago, he still sent money to his family back home. Before he came to Greece in 2007, he had learned about the country in school: the rich culture and lengthy history, the famed archeological sites and the ancient philosophers.

Although life was already challenging enough as an undocumented migrant during Gias’s first few years in Athens — a 10-hour workday would only earn him between 20 and 30 euros — in the early 2010s, a severe economic crisis took hold of the country. As poverty deepened, left-wing parties pointed the finger at capitalism and the harsh austerity measures the government introduced in tandem with Europe’s economic bailout packages, but a once-obscure neo-Nazi party called Golden Dawn offered a far simpler explanation: it was the refugees and migrants, the party insisted, who were responsible for Greece’s woes.

To those who had fled warzones and economic catastrophes, Greece had offered the hope of stability and safety. The country now became a place where they had to navigate survival. As Golden Dawn’s popularity grew, its supporters took to the streets to hunt down refugees and migrants. The mobs often beat, bludgeoned, robbed, and stabbed whomever they caught. “They were treating us like animals,” Gias recalled, “like we weren’t humans.”

One night in 2011, Gias recounted, he found himself in a far-right mob’s crosshairs. While walking home from dinner with a friend in downtown Athens, he came upon a group of masked men who were “searching for foreigners,” he said. The men threatened him at knifepoint and eventually let him go, but he knew how much worse it could have gone: for months, he had heard stories of Greek men chasing down people who looked like him, yanking them off buses, or kicking in the doors of the homes where they lived. Among refugees and migrants, he said of that period, “There was a lot of fear.”

As Golden Dawn vied for seats in the parliament in 2012 legislative elections, some analysts wondered whether electoral success would tamper the party’s violent tendencies. Yet, as one party candidate told a documentary filmmaker, “After the elections, the knives will come out.”

Nearly 7% of voters cast their ballots for Golden Dawn that year, propelling the neo-Nazi party into the Hellenic Parliament for the first time, and in the months that followed, the knives did come out. In January 2013, two alleged Golden Dawn supporters knifed and killed a 27-year-old Pakistani man named Shahzad Luqman, who was working in a vegetable market to help pay for his sisters’ weddings back home. It wasn’t until nine months later, when a party member fatally stabbed the Greek anti-fascist rapper Pavlos Fyssas, that the government belatedly arrested dozens of Golden Dawn members and eventually placed 69 on trial for operating a criminal organization.

Widespread public opposition mounted, and even though Golden Dawn became the third-largest party in the parliament in January 2015, its fate was now grim. Dozens of members were on trial, and its supporters often faced pushback from anti-fascists any time they gathered in the streets. In the July 2019 legislative elections, the party failed to attract enough votes to remain in the parliament, and in October 2020, a panel of judges declared Golden Dawn a criminal organization and banned it.

The day of the verdict, Gias woke up at his home in the Ampelokipoi neighborhood, not far from the courthouse where Golden Dawn’s case was decided. When he went outside, thousands of people were celebrating in the streets. “We were very happy that they were going to jail,” he said. Still, hundreds of thousands of voters had cast their lot behind the party over the years. “They were still outside,” Gias added, “and they hadn’t changed their minds about us.”

“The Alarm is Ringing”

Many of the Golden Dawn defendants went to prison, including its founder Nikolaos Michaloliakos and several former parliamentarians, but as countries across the world are now relearning, neither electoral defeats nor legal mechanisms are enough to snuff out fascism and xenophobic violence.

During last year’s legislative elections, the ruling right-wing New Democracy remained in power after campaigning, in part, on promises to continue its crackdown on refugee arrivals at sea and by land. In early June, the Adriana, an Italy-bound boat carrying hundreds of refugees and migrants, departed from Libya and went astray into waters off the Greek coast. The boat sank, killing some 600 people, and accusations soon emerged that the Greek coastguard had caused it to capsize while attempting to tow it. (The government has denied that claim, and an investigation into the incident remains ongoing.)

A little more than a week later, 40% of voters put New Democracy back in charge, while nearly 13% cast their ballots for one of three new far-right, anti-migrant parties that entered the parliament. One of those parties, the Spartans, has direct links to former Golden Dawn members, including the neo-Nazi party’s onetime spokesperson, Ilias Kasidiaris. (Along with 11 Spartan lawmakers, Kasidiaris, who unsuccessfully ran for mayor and won a seat on the Athens city council late last year before resigning, is currently on trial again, this time for alleged electoral fraud.)

This June, Golden Dawn founder Michaloliakos, who has spent much of his time in lockup reiterating his praise of the violent party he once oversaw, received an early conditional release from his 13-year prison sentence. Public outrage mounted, and a prosecutor challenged the decision, an effort that sent Michaloliakos back to prison. In October, Kasidiaris similarly applied for early release, although an appeals court denied the request.

“There was a lot of fear.” – Sheikh Gias

Even with the country’s once powerful neo-Nazis behind bars, Greece has hardly become a friendlier place for the people who make dangerous journeys in search of a new life. As the European Union pours funds into policing its external borders, including in Greece, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis has time and again described migration to the country as “an organized invasion of illegal migrants,” even vowing to build a wall on the northeastern land border with Turkey. Reports of border violence — including pushbacks, or extrajudicial expulsions, oftentimes paired with threats and beatings at the hands of border guards — have become so routine that they rarely attract the attention they once did.

More often than not, it is now the state itself, rather than flag-waving mobs, that carries out the most shocking displays of violence against refugees and migrants, forcing boats back into Turkish waters or stripping and beating people who cross the border. Still, the kind of hate crimes Golden Dawn once became known for haven’t stopped. Between 2021 and 2023, the three years following Golden Dawn’s conviction, the RVRN tallied 304 hate crimes in Greece, 49% of which targeted refugees and migrants or humanitarians working with them. In one such instance last summer, far-right politicians amplified a conspiracy theory that blamed refugees for the very fires that killed dozens of displaced people making the perilous walk from Turkey to Greece, and vigilante militiamen leapt into action, kidnapping 13 migrants and forcing them into the back of a trailer.

Eva Cosse, an Athens-based researcher at Human Rights Watch, explained that there was always a “danger” in assuming that the Golden Dawn conviction would inevitably lead to an end in hate crimes and far-right attacks. “First of all, not all the attacks were conducted by Golden Dawn in the past,” she told me. “And the fact that they were convicted doesn’t mean that their ideology has disappeared.”

For the Muslim Association of Greece’s Anna Stamou, the recent spate of violence stems from the normalization of anti-migrant rhetoric and the mainstream left’s failure to join the fight against it. “Now we have an ultra-right wing government whose rhetoric is anti-immigrant, and then there are groups [in the streets] that take action,” she told me. Without a firm pushback from the broader society, she fears the violence could once again escalate. “The alarm is ringing, but who’s waking up? Where are the left parties? Who is there to stop [the far right]? Their conscience?”

“All the Scum Work Together”

Greece’s electoral left may have largely collapsed, but committed anti-fascist groups continue to face down the far right. Even at the height of Golden Dawn’s popularity, when the party commanded a worrisome street presence and could dispatch attack squads to neighborhoods in many cities around Greece, the far right never went unchecked.

Leftists and anti-fascists often rallied in opposition to the party, sometimes even attacking neo-Nazi groups’ headquarters or brawling with far-right jackboots in the streets. Take, for instance, the hours-long blockade anti-fascists imposed on the office of the far-right Popular Greek Patriotic Union (acronym: LEPEN, a wink to its fellow travelers in France) in September 2016, an action that prevented the party from celebrating the inauguration of its new headquarters. Or one day in March 2017, when a handful of black-clad anti-fascists took sledgehammers to the façade of a bookstore attached to a Golden Dawn office on the capital’s Mesogeion Avenue.

Yet, more often, this struggle takes the form of organizers attempting to build broad political alliances to isolate far-right groups. On any given day, then as now, you can find people — socialists, anarchists, and campaigners for migrant rights — sounding the alarm on what they fear is a concerted far-right effort to expand the movement’s base of support. They post up on corners in neighborhoods around the capital, picketing, handing out fliers, and asking passersby to help, as they often say, get “the fascists out of our neighborhoods.”

In late October, much of their movement’s focus centered on an annual neo-Nazi gathering in a northern Athenian suburb called Neo Irakleio. There, far-right agitators assemble each year outside a defunct Golden Dawn office to commemorate the slaying of two party members 11 years ago. On Nov. 1, 2013, not long after Fyssas’s murder, masked gunmen opened fire and killed the pair. A previously unknown group that called itself the Militant People’s Revolutionary Forces later issued a communique claiming credit for the deadly attack. Supporters of the country’s far right have commemorated those deaths each year, and since Golden Dawn disbanded, new, smaller neo-Nazi groups have taken up the mantle. Last year, hardline neo-Nazis from across Europe traveled to Greece to participate in the event — authorities arrested 21 Italians from the fascist group CasaPound at the airport — and many followed counter-protesters around town and attacked them.

A few days before this year’s annual commemoration, anti-fascists held a solidarity concert in Neo Irakleio and called on locals to band together against the neo-Nazis. When the night of Nov. 1 came, I made the trek north to the suburb. A few dozen people gathered outside the Golden Dawn office, waving flags and lighting flares.

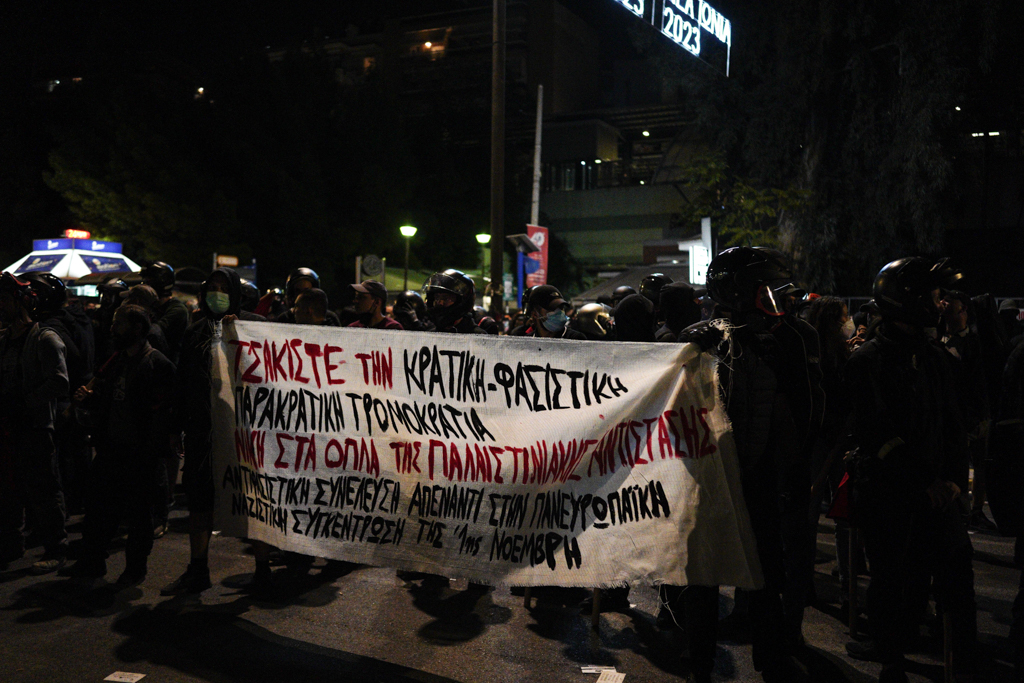

A couple blocks over, knots of riot police had formed on the corners of the main square, the cafes and bars behind them crowded and blasting pop music from their speakers. When I showed up, there were only a few early arrivals to the counter-protest standing around, passing out leaflets to whomever would take one. But a few moments later, a sea of young people rushed out of the metro stop. Anti-fascists, many donning motorcycle helmets or black masks and propping sticks with black-and-red flags on their shoulders, lined the curbs along the street, unfurled their banners, and began to chant. “Now and always, like in 1940,” they began, “we will fight poverty and fascism.”

Before the march took off, Petros Constantinou, director of an anti-fascist activist group called the Movement United Against Racism and the Fascist Threat, or KEERFA, stood near a block of demonstrators gearing up to rally. For years, KEERFA has shared an office with the Pakistani Community of Greece, and whenever a new attack happens, the two groups work together to get the details into the press, organize protests, and support the victims, who are often undocumented and afraid to go to the authorities or file police reports. I asked him how frequent such violence is at the moment, and he said that it was “escalating” once again. “The attacks are happening closer and closer together.”

When the march finally set off, riot police followed on either side. Up front, officers shouted at their radios, informing their colleagues where the protesters were headed. Around 500 people pressed forward along the residential streets, stopping now and then to chant as bystanders stood outside cafes and shops to watch. “We’ll crush fascism,” a banner in the front row promised, “and the system that feeds it.”

Whenever the march veered from the planned route, police officers rushed ahead and scrambled to redirect traffic. Years back, a demonstration like this might have ended with Molotov cocktails and stones raining down on the neo-Nazi crowd, with riot cops clouding the streets with tear gas to push back the counter-demonstrators, but the police rerouted the march before it could reach the group outside Golden Dawn’s former office. An hour after it had begun, the demonstration ended at the spot where it had started. “Cops, TV, neo-Nazis, all the scum work together,” the marchers chanted before breaking apart. “Fascist thugs, the gallows are coming.”

“A Very Difficult Life”

Meanwhile, the attacks continued here and there. In late October, a 52-year-old Bangladeshi man named Aman Ali, a friend of Sheikh Gias, was walking home from a short-term gig as a cook at a hotel in Kallithea, a neighborhood in Athens, when he came across a group of eight young men dressed in all black. In a statement KEERFA later put out, Ali said the men lined up “like soldiers” before they rushed him. The first to break away from the pack kicked Ali down onto the pavement, he said, and another punted him hard in the face. The mob cursed him and hurled racist slurs his way. After the ambush ended, Ali went to the hospital, where he had to get 12 stitches in his mouth.

After the Oct. 20 protest in Sepolia, I’d made plans to meet with Mohammed Aslam to speak more. I messaged him a few times, but it took him a couple weeks to respond. He was busy working, and renewing his residency documents had proven a struggle.

When we finally met at a Pakistani restaurant downtown in late November, his face was slack and exhausted, and he spoke softly. He explained that, to his knowledge, the police still hadn’t caught any of his attackers. (The Hellenic Police’s press office did not respond to requests for information about the investigations into the attacks on Aslam and Ali.) Aslam’s stitches had healed, but he didn’t have enough money to fix his teeth. He was relying on ibuprofen and other over-the-counter medicines for the lingering pain, and whenever he woke up in the morning, he explained, he blew his nose and found blood on the tissue. Worse yet, one of his cousins had passed away in Pakistan in late October, and yet again, his pending residency renewal meant he could only attend the funeral by video call.

Punjabi music blasted from a TV tacked to the wall. Customers came in and out of the restaurant, some picking up takeaway orders and others sitting for a plate of biryani. Aslam lifted his phone and showed me photos of his family in Pakistan: his wife, his daughter, and his late mother. It had been nearly two years since he was last able to visit Pakistan, and the more time that passed, the more the weight of missing his family wore on him. As we spoke, he drifted into his own thoughts while swiping through family photos. After a while, he said, “It’s a very difficult life.”

More than a month had gone by since the attack, and he still felt fearful whenever he had to go out around town. But his wife, a doctor back in Pakistan, worried far more, and he said they had taken to spending more time on the telephone so that she would know he was safe. I asked him if he had considered what justice might look like to him. He thought about it for a while. “I want every foreigner to have a good life in Greece,” he finally said. “Because Greece is supposed to be Europe. … If it continues like this, how can I stay here?”