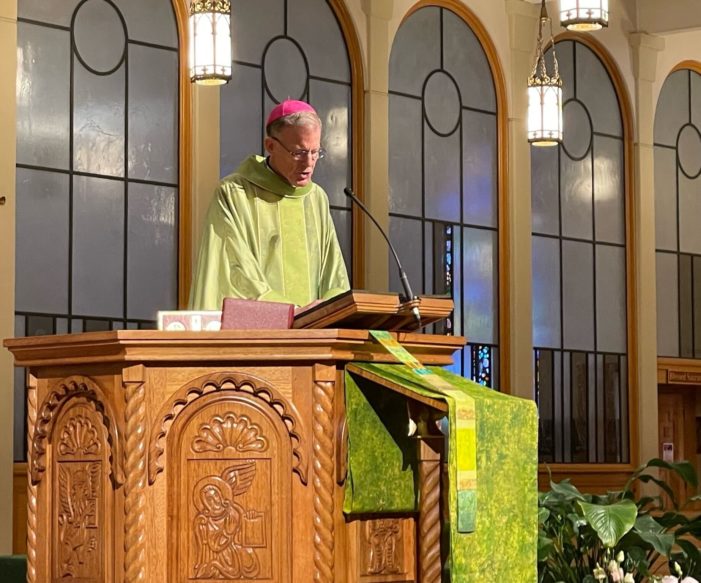

At least 100 parishioners must have been in attendance at the special mass at the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi on Aug. 9, 2022. The Tuesday afternoon service at the historically significant church did not fall under the usual schedule. Following an afternoon rich in monsoon thunderstorms, the clouds cleared, allowing regulars and visitors alike to file in to hear what, exactly, the Archbishop of the Santa Fe Archdiocese had to say about the work of peace.

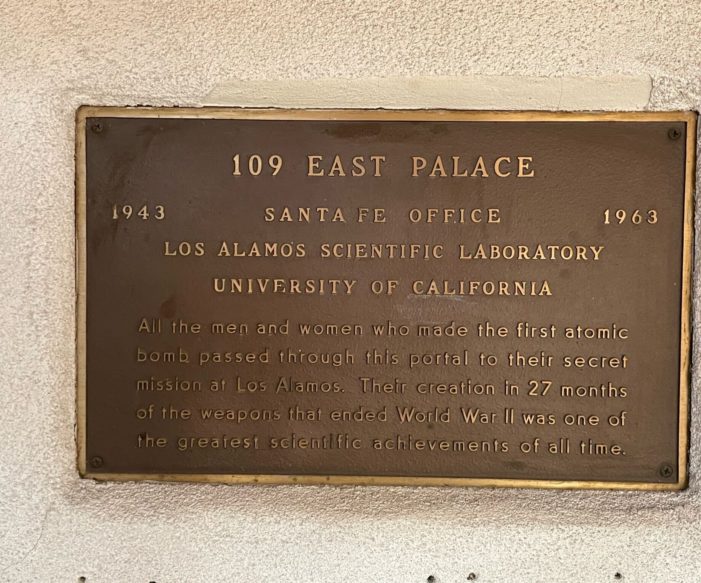

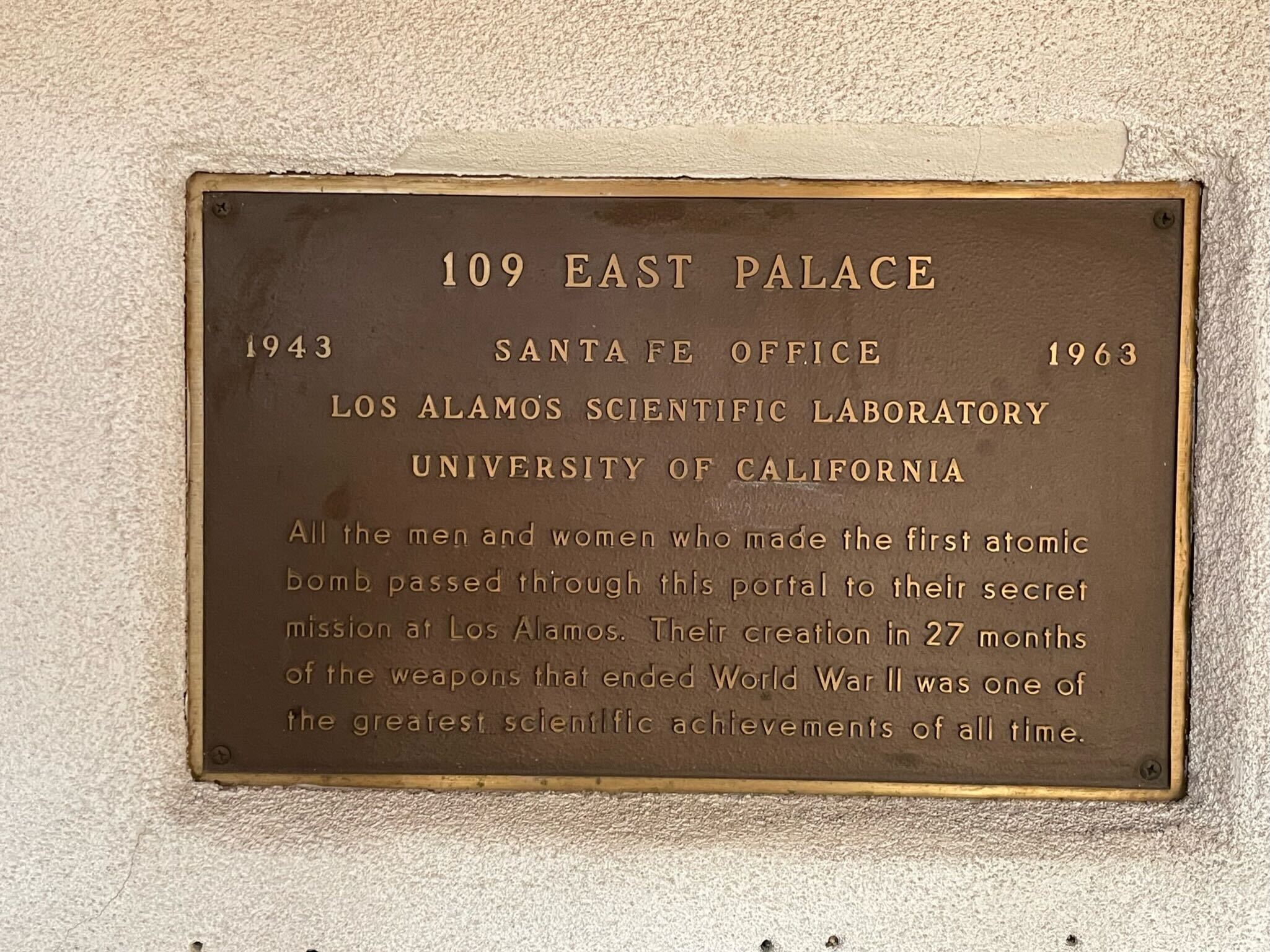

“In the way that 109 East Palace was the gateway to nuclear oblivion, I hope that the Basilica of St. Francis can be the gateway to global nuclear disarmament,” John C. Wester, Archbishop of Santa Fe, told the assembled crowd.

The address is instantly familiar to those fluent in nuclear history and opaque outside of it. During the Manhattan Project, the US effort to develop and build an Atomic Bomb in Los Alamos, 109 East Palace was the place to arrive before being covertly whisked away to the lab.

When it comes to salvation from nuclear oblivion, faith in the righteousness of the task alone is not enough. There must be work that makes it real.

It was the work of Los Alamos that made Aug. 9 the occasion for a mass dedicated to nuclear disarmament. On Aug. 9, 1945, the US dropped Fat Man, the second and so far last nuclear weapon used in war. The bomb fell on Nagasaki, a Japanese city hastily added to the targeting list. While the bombardier claims the clouds parted for visual confirmation of the target, it is at least equally plausible the crew decided to drop the bomb by radar targeting and fly back to base, instead of ditching it in the ocean or crashing on the way back.

When Fat Man hit Nagasaki, it killed an estimated 40,000 or 70,000 people. Wester consistently stuck to the high estimate i remarks, emphasizing both the real horror of the dropped bombs and the terrible scale of destruction existing weapons promise.

“For me, it’s the lethalness of them,” Wester told me in an interview the Friday before the special mass. “The absolute destructive power of warheads, of just one current modern day warhead of average impact is incredibly more powerful than those bombs dropped on Hiroshima, Nagasaki, 10,000 times more, incredibly more destructive,” he said. “And we don’t have just one, we’ve got around 13,000 nuclear warheads currently in the world today. The mind can’t really wrap itself around how destructive… it’s like trying to grasp what a light year is.”

The challenge of nuclear disarmament is partly a problem of scale. Russia is just shy of 6,000 warheads while the United States has about 5,500. The seven remaining nuclear armed countries possess a combined 1,300 or so warheads, with China the third most at a distant 350 and North Korea with the least at an estimated 20 warheads (and increasing). That is, all told, a fast decline from the global peak of over 70,000 warheads in the late 1980s, but it’s a number that’s increasing. Perhaps more importantly, it doesn’t capture the extent of the nuclear modernization efforts underway in countries like the United States and Russia, which are updating and remaking existing warheads into newer weapons.

“Every single human communication is fraught with error and misunderstanding. Well, that’s really scary when you consider a communication regarding launching a nuclear war between two major powers,” said Wester. “When God is in charge, I don’t worry so much, but when human beings are in charge of that kind of destructive power, I worry a lot.”

THE SANTA FE TALE

Against all of this, the Archbishop sets a church in New Mexico and the power of faith across religions to drive people to change the future of nuclear weaponry, starting with a special focus on New Mexico.

The city of Santa Fe, the Basilica, and present Pope Francis all take their name from St. Francis of Assisi, revered as an advocate of nature, peace, and the poor. In Wester’s “Living in the Light of Christ’s Peace: A Conversation Toward Nuclear Disarmament,” a booklet distributed after the mass, he makes special note of the sainted name.

“Ironically,” Wester writes, “the US government probably spends more on nuclear weapons within the boundaries of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe than any other diocese in the country and perhaps the world.”

Both Los Alamos and Sandia National Laboratories, as well as the Kirtland Munitions Storage Complex that contains up to 2,000 nuclear warheads, fall within bounds of the archdiocese. The atomic bomb was designed, built, and assembled in Los Alamos. At Sandia, atomic bomb design and production was refined. The Trinity Site is where the first nuclear bomb was detonated, its fallout plume creating in the downwinders the first nuclear victims, and it too falls within the geograpic reach of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe.

While the uranium mines of the Southwest fall more under the Gallup than Santa Fe diocese, the nuclear enterprise in the state is broader than just the highly compensated lab workers who specifically make weapons. Gallup sits within the Navajo Nation, home of the Diné people, and it is in these and pueblo lands that the burden of nuclear extraction has fallen most heavily. In a panel following the mass, former governor of Cochiti Pueblo Regis Pecos said, “We cannot be an energy colony for the rest of the country. Our Land of Enchantment cannot become the wasteland for our country.”

In a figure that Wester returned to in the mass, in the after-mass interfaith panel, and in printed material, the Department of Energy is spending $9.4 billion for nuclear weapons in New Mexico in 2023. The state’s budget for that year is only $8.5 billion.

That number is a specific and cherished rebuttal to lines of questioning about how much money the nuclear enterprise brings to the state of New Mexico specifically. That money is, at best, unevenly distributed, with the highly skilled and educated laboratory workers of Los Alamos county disproportionately well off, while New Mexico broadly remains a grim outlier for child poverty statewide.

Redirecting that spending toward other avenues, like schools, water resources, and wildfire protection, are part of a broader moral aim about how New Mexico can move beyond an economy oriented around engines of destruction. Pecos, emphasizing that spending and extracting for nuclear enterprise was an ideological choice, said “we must denounce the doctrine of discovery and manifest destiny” that make such a choice possible.

Another panelist, Reverence Dr. Holly Beaumont of the Interfaith Worker Justice-NM, said an economic assessment of the nuclear industry in New Mexico is incomplete without looking at the harms from testing, from poor nuclear waste management, and especially from uranium mining, which has taken a special toll on Diné and Pueblo people.

The arguments are structured as calls to win over legislators, for attendees to repeat and train friends on in an explicitly nonpartisan call to shift New Mexico away from its recent restart of nuclear weapons production to instead do the work of disarmament. As such, the panelists sometimes spoke at cross purposes on the topic of peace.

The panelists shared language on universal, verifiable disarmament, though one reason for disarmament was to change the kinds of wars that can be fought, rather than prevent them. Citing President Joe Biden’s caution in directly confronting Russia on Ukraine, Beaumont said nuclear arsenals are “preventing us from addressing Putin’s genocide. We cannot save our brothers and sisters because we are terrified of starting the next war.”

Jay Coghlan of Nukewatch, invited by Wester to answer an audience question about Ukraine having lost deterrence when it returned Soviet nuclear weapons to Moscow, emphasized that Ukraine never had the controls to actually detonate nuclear weapons stored on its territory. Coghlan then echoed Beamont’s statement, saying “we can flip the argument, say that Russia is shielded from consequences because it has nuclear weapons. Deterrence has been flipped on its head.”

FROM “TRINITY” TO THE PRINCE OF PEACE

If nuclear weapons permit the powerful to wage war on the weak, and prevent allies from coming to their defense, then what can be done to end the threat posed by the weapons? Wester, in homily, told the assembled congregation that with Pope Francis the Catholic Church has moved beyond a past conditional acceptance of deterrence, in part because no country is willing to commit to minimal deterrence. Arsenals of hundreds and thousands of warheads are built to wage nuclear war, not keep it at bay.