I have been up to the dry, shrubby lands of northern Utah’s Great Basin twice recently, first to visit Northrop Grumman’s final assembly plant for the new intercontinental ballistic missile. The facility, which Northrop workers call the Promontory plant, snakes along over six miles of single-lane highway through dunes dotted with bunkers that engineers use to watch fiery missile tests, a dangerous endeavor that has killed at least nine workers over the plant’s nearly six decades of existence.

The second time was to visit the new Heravi Peace Institute at Utah State University, which aims to train students in peacebuilding the way other academies train students for warfighting. It’s a rare institute of its kind both in the intermountain west and as one serving a public, land-grant university where many of the students work to pay their way through school and have never had the opportunity to travel abroad other than on Mormon missionary trips, a professor there told me.

That weapons of mass destruction and a peacebuilding institute of mass instruction ended up cohabitating on the northern side of the Great Salt Lake is, in its origins, a story about place and what different people saw when they saw that vast arid terrain.

Origins of Nukes in Utah

First, here’s what the Thiokol Chemical Corporation’s Director of Market Development Louis M. Sherman saw there. In 1956, Sherman was tasked with scouting a new location for a plant to produce solid-fuel rocket motors, something the newly formed Air Force was keen to buy from Thiokol because it meant the military could launch intercontinental ballistic missiles in a matter of minutes rather than the several hours it took to prepare liquid-fueled missiles for launch. The plant needed to be away from coastlines, Canada, East Coast industrial sites, population, and in an area “of little or no use to anyone,” according to Weber State University Historian Eric G. Swedin in his account of the plant’s origins in the Utah Historical Quarterly.

Sherman told a Utah official that he needed “a minimum of 2,500 acres of rough, cheap, unproductive land . . . serviced by good transportation facilities of rail, highway, and air . . . [and] he did not want close neighbors due to the explosive nature of their business, but he still required a good labor force of 300 to 500 workers.” The hilly sagebrush lands of Promontory checked the boxes.

The plant opened in 1957, and Northrop Grumman, nowadays the world’s largest nuclear weapons contractor, took ownership of the plant via an acquisition in 2018. Over the coming years, it will manufacture more than 600 Sentinel ICBMs there, which will be loaded with nuclear warheads and then dropped into silos across the American West, on continuous alert for launch orders to shoot over the North Pole and reach Russia or China in about 30 minutes

Iran and Utah

Mirza Ali Gholi Khan, an advisor to the Shah of Iran, saw something else in northern Utah. In 1912, the president of Utah State University, created as an agricultural college in 1888, went to a conference on international dry farming in Alberta, Canada. There, he met a young Iranian diplomat, which led to Khan being invited to speak at USU’s baccalaureate services in 1915.

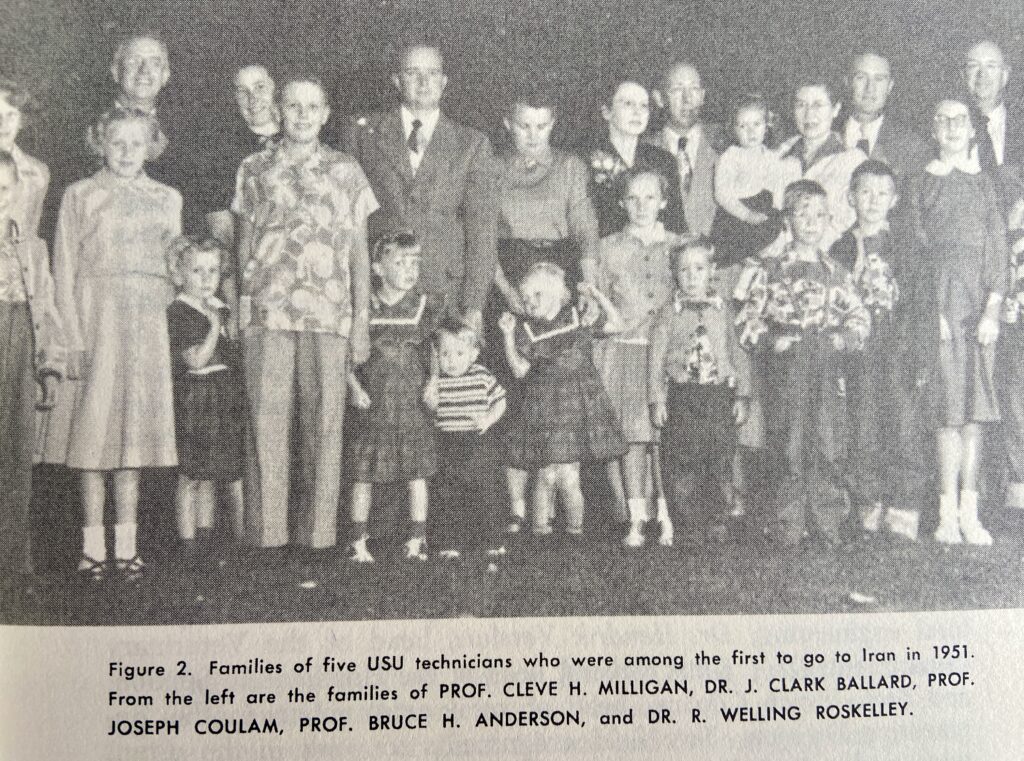

Khan’s speech described “the geographic and other similarities between the two great areas and noted the similar spiritual interests of the two peoples,” according to the 1963 book Iran and Utah State University: Half a Century of Friendship and a Decade of Contracts. Iranian exchange students began studying agriculture at USU, and in 1950 Iran became the first country to sign up for the Truman Administration’s Point Four program, a foreign aid initiative that sent American technical experts to assist low income countries. The government chose USU for its agricultural know-how and sent more than 50 technicians and their families to every province of 1950s Iran for research and training on increasing crop and livestock yields.

(You may be wondering how I came across a six decade-old book about Logan-Iran ties; Mehdi Heravi, the peace institute’s namesake, keeps copies on hand and gave me a remarkably non-musty one when I met him.) Once in Iran, the technicians took note of the “many similarities between Iran and Utah,” including the low rainfall, the Urmia salt lake that was comparable in size to the Great Salt Lake, and its location among two large mountain ranges.

Mehdi Heravi: From Tehran to Logan

USU’s main campus is in Logan, a scenic valley college town about an hour and a half from Salt Lake City through a beautiful mountain pass known as Sardine Canyon. Mehdi Heravi ended up there in 1958 because of those USU technicians in Iran. From an affluent family in Tehran, his father, a graduate of the Sorbonne in Paris, was an agricultural professor at the University of Iran. He sent Mehdi off to England for boarding school when he was nine with the intention of him going on to university in Europe. But Mehdi, an aficionado of American films, begged his father to let him study in the United States, dreaming of driving a big car in Detroit or walking among movie stars in Hollywood. His father turned to those USU technicians for advice.

He asked them, “Where can I send my son in America so he wouldn’t become a smoker or a drinker?” Mehdi told me. “They said, ‘Professor Heravi, we have the best place in the world, Utah.’”

When 16-year-old Mehdi arrived in Salt Lake City in 1958, he thought the captain had rerouted due to a mechanical error. He didn’t see anything that looked like much of a city from the plane’s window, and the terminal was barely larger than a living room. Then, he picked up his luggage, got on a Greyhound and soon arrived in Logan, where an enduring love affair with the town soon began. He served as the USU student court’s chief justice, chair of the school’s International Days, became the first international student to win an election to the student senate, earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree, then worked as a teaching assistant to stay around Logan longer. He only reluctantly left to pursue a PhD at American University in Washington DC.

“I don’t know if peacebuilding is the answer, but we’ve got to try something.”

“Everything worked out just perfectly,” Heravi, nowadays a philanthropist who supports an orphanage in Iran, cerebral palsy organizations, and scholarships at USU, told me. “I’m still in love with Logan, with Utah State, and I have nothing but fond memories of my days at Utah.”

But it wasn’t just his idyllic time as an exchange student in a remote Utah town that led him down the path of peace and coexistence. After earning his PhD, Mehdi moved back to Tehran, where he served as the vice president and provost of the National University of Iran until the Iranian Revolution upended the country’s political and social order. He was arrested and held in solitary confinement for nearly a year. He returned to the US and emerged from the experience with a newfound commitment to tackle what he told me is the “main struggle” of humankind, which is “for people to learn to live together in peace and harmony.”

Peacebuilding Un-siloed

I first heard about the Heravi Peace Institute from Patrick Mason, a professor of Mormon History and Culture at USU who may be the country’s most knowledgeable academic on a crucial moment in the history of disarmament, which is the church’s remarkable dissent in 1981 against the MX missile, a nuclear weapon which the Reagan administration would later mostly scrap.

Mason and his colleague, Jennifer Peeples, told me that the institute was not started from scratch but instead is a grassroots effort built off “pockets of people” who are “making interconnections between existing strengths” in various disciplines that point toward peacebuilding. For example, in addition to Mason’s specialty in church history and culture, Peeples teaches environmental communications (she told me about sending off students to report on Superfund sites across Utah, including Hill Air Force Base, which oversees the new ICBM’s production), and a colleague in the political science department researches the geography of war and peace.

Peeples said the institute offers certificates rather than a full degree program in areas like global peacebuilding and conflict management because they want peacebuilding to be seen as an “add-on” to other degrees rather than a siloed field of study. Studies range from the hyper-individual — such as courses that teach students to mediate interpersonal conflicts, like among testy roommates — to the historical and global, including an upcoming spring semester in Vietnam that will give students an up-close look at a country that’s been on the receiving end of US bombs and where Agent Orange is still in the soil. Peeples told me the study abroad opportunities are particularly valuable for the USU’s many students of modest means, who often are working to pay their way through college and marry and start families young, leaving them with a narrow window of time to live outside the United States.

The average USU students started high school during the 2016 Trump-Clinton election, have grown up witnessing the realities of climate change, and “have never known a world in which the US is not at war,” Peeples told me. Anxiety and depression among them, she said. One told her: “I don’t know if peacebuilding is the answer, but we’ve got to try something.”

Heravi told me that such an institute might be more common at an elite university that feeds into conventional careers of power and influence, but that he wanted the institute at USU both because he loves Logan and because he’s enthusiastic about the young people there.

“I hope they would be the leaders of the values of peace,” he told me. “War is not the answer to human problems.”

Top photo: The sun sets over the campus of Utah State University, published in February 2019 (Joshua Hoehne/Unsplash)