In the late 1950s, despite facing high personal risks, a group of doctors from Kazakhstan’s Institute of Regional Pathology carried out a large-scale medical expedition to the villages near the Soviet nuclear testing site in the Semipalatinsk region. Their three-year effort generated clinical data that showed that nuclear tests harmed people, resulting in numerous illnesses.

Today, the national security field reckons with the fact that nuclear testing has caused significant harm to communities and the environment. Our knowledge, however, would not have been possible without the bravery and courage of medical professionals like those in Kazakhstan, who not only conducted this kind of research against all odds, but also recorded the truth.

HOW IT BEGAN

In the late 1940s, the Soviet military built a sprawling nuclear testing site in the eastern part of Kazakhstan. With more and more land taken from the local use, its territory eventually grew to the equivalent of Belgium. In 1949, the first Soviet atomic test rocked the Kazakh steppe. The land that provided livelihood to locals by offering pastures to the livestock turned into a ground for nuclear experiments. Military activity upended the steppe’s complex and fragile ecosystem; even mice and groundhogs ran away.

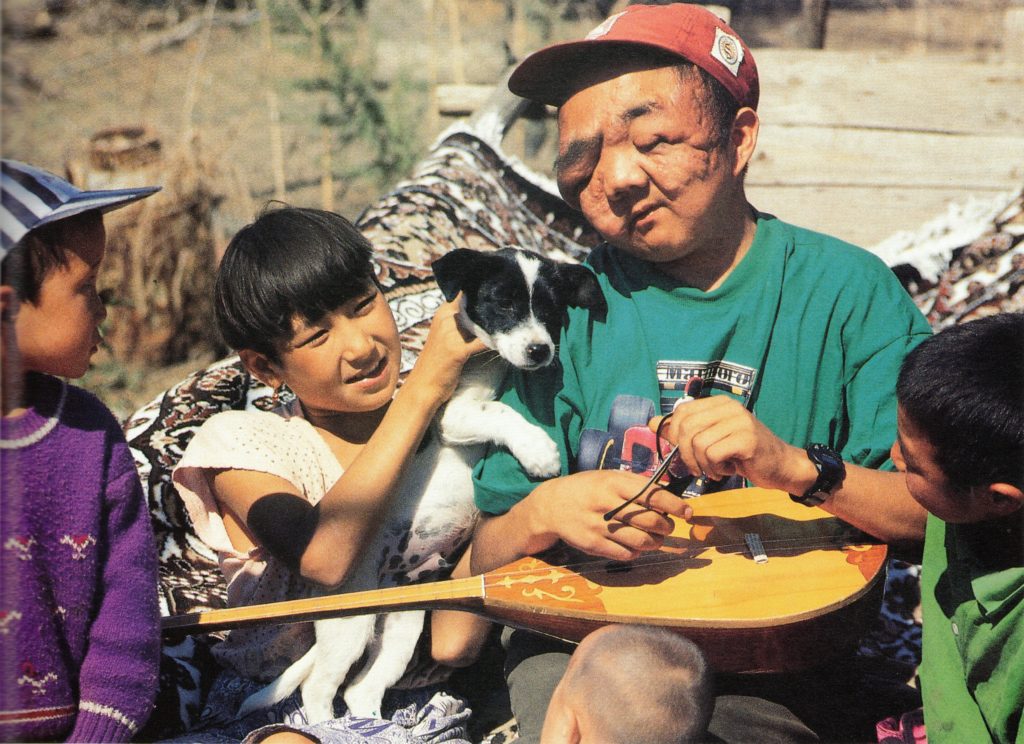

Nuclear mushrooms became an unwelcome part of the Kazakh landscape. Unaware of the dangers, locals, including kids, gazed at enormous pillars of dust mixed with radioactive particles rising to the sky. Animals ate grass laced with radioisotopes. Authorities, presumably eager to avoid injuries from falling objects and broken glass during nuclear tests, ordered people to stay outside during particularly powerful explosions. That made residents even more vulnerable to nuclear fallout traveling over their villages. Locals ate contaminated meat and drank contaminated milk. Even if the ionizing radiation was invisible, very soon, its effect on people’s health became evident, even to the naked eye.

Nuclear mushrooms became an unwelcome part of the Kazakh landscape. Unaware of the dangers, locals, including kids, gazed at enormous pillars of dust mixed with radioactive particles rising to the sky.

Locals’ health deteriorated. Pregnancies that did not end in miscarriages often led to complicated births. Some babies were stillborn, some were missing limbs and fingers. Suicides, previously unheard of in the Kazakh steppe, were on the rise. What was happening?

The Soviet military leadership wasn’t interested in protecting the civilian population from radiation and denied any contamination or harm from nuclear tests. Locals living near the nuclear testing site were collateral damage. At the same time, what radiation did to humans could provide valuable data for understanding the effects of a potential nuclear war. Small teams affiliated with the Soviet military-industrial establishment conducted limited studies in the region, but their findings were classified.

THE HUMAN COSTS OF NUCLEAR TESTING

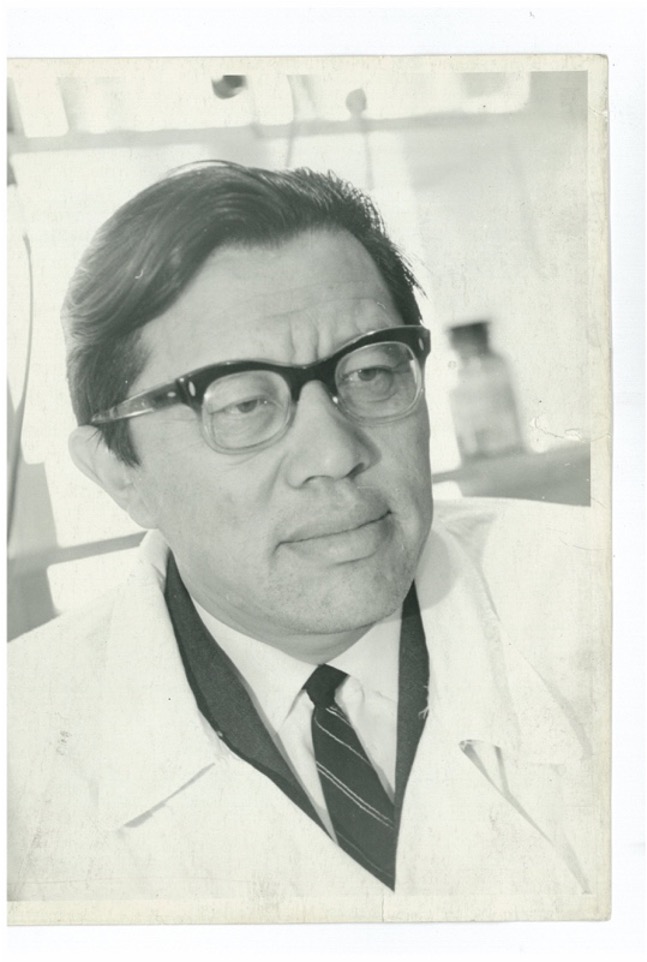

In 1957, in the atmosphere of Stalin’s regime that instilled fear of repressions, a Kazakh doctor, Bahiya Atchabarov, the head of the Institute of Regional Pathology in Almaty, asked his superior, the head of Kazakhstan’s Academy of Sciences Kanysh Satpaev, for permission to lead a medical expedition in the Semipalatinsk region. Atchabarov’s Institute was part of the Academy of Sciences. Satpaev, a prominent scientist who founded metallogenic science in Kazakhstan, gave his authorization. The Soviet Health Minister Maria Kovrigina, who knew from her Kazakh colleagues about health problems in the region, supported the effort.

In his memoirs,* Atchabarov recounted how a witness to another high-stake medical expedition told him a troubling story as a warning of what could happen to him. In the 1930s, a medical expedition from the Sverdlovsk Institute of Occupational Hygiene surveyed the health of people who were dispossessed and exiled to Siberia. The expedition team uncovered severe avitaminosis. The expedition’s head concluded that those people should be returned to their native land to avoid mass deaths. For that recommendation, he became a victim of a purge.

Fully aware of the high stakes and personal danger, for three years, medical professionals from the Institute of Regional Pathology conducted clinical observations of more than 3,500 people who lived near the testing site. They also examined more than 2,000 people from other areas of Kazakhstan to compare their health to those who were exposed to ionizing radiation.

The medical team reflected the multi-ethnic composition of Kazakhstan and included Kazakhs, Russians, and other citizens contributing to the effort. The scientists diligently recorded what they saw, despite the risks for documenting the truth. In the atmosphere of a tightly controlled military narrative that denied any harm from nuclear tests, their clinical data screamed the opposite. The medical records they were creating showed that the Soviet government’s most important national security project was ruining the health of its citizens.

Kazakhstan’s medical team encountered a grim picture. Most locals they examined in the villages next to the nuclear testing site suffered various ailments. Neurological conditions made people tired, caused headaches, and dizziness. Some were losing their swallowing reflex, the body’s defense mechanism against choking. Blood did not circulate well in the brains of people in contaminated settlements. People with long-term exposure to high amounts of radioactivity experienced changes in the threshold for pain sensitivity and in their sense of taste and smell, as well as changes in nose, ear, and throat. Women suffered from disrupted menstrual cycles, pathologies in genitalia, and other gynecological problems.

The doctors observed that residents who lived in proximity to nuclear tests aged prematurely. In some cases, they looked ten years older than their age because of infectious diseases, somatic diseases (a condition when extreme focus on pain and fatigue leads to emotional distress), and generally unfavorable living conditions.

Often locals simultaneously suffered from a range of symptoms, and Kazakh doctors concluded that deficiency in Vitamin C and exposure to radiation were the main culprits. Dr. Atchabarov called the phenomenon “Kainar Syndrome” after one of the villages they visited. People in “cleaner” regions used as a control group for the study also had health issues, but the gravity and number of symptoms weren’t near as bad as in the contaminated areas. Radiation exposure explained the difference between the health of people living near nuclear tests and those in other parts of Kazakhstan.

Animals suffered even more than humans because they spent all their time outside, ate contaminated grass, and remained in close contact with soil that absorbed radioactive particles. The Institute of Regional Pathology team studied thousands of animals, again comparing contaminated areas with areas far from the testing site. Animals exposed to nuclear tests suffered from blood, liver, lung diseases, damaged lungs, bleeding in their respiratory systems, mouths, genitals, and altered brain tissue. Post-mortem tests found strontium-90 in the bones of sheep and dogs. Known as “bone-seeker,” strontium-90 lodges in bone and bone marrow and causes cancer of the bone, nearby tissue, and leukemia.

Our knowledge would not have been possible without the bravery and courage of medical professionals like those in Kazakhstan, who not only conducted this kind of research against all odds, but also recorded the truth.

HOW THE TRUTH STAYED HIDDEN

The findings from a three-year effort filled in 12 volumes with clinical data, observations, and comparison data. In 1961, Kazakhstan’s team traveled to Moscow and presented their research at a “closed” conference at the Institute of Biophysics, a medical institution closely affiliated with the Soviet military. Behind closed doors, Moscow experts dismissed the findings of Kazakhstan’s doctors, arguing that locals’ poor health was the result of severe vitamin deficiency and poor hygiene. The main tactic of the Institute of Biophysics was to criticize the methodology, thus questioning all subsequent findings.

Kazakhstan’s doctors pushed back against the notion that vitamin deficiency was to blame. They explained that while locals lacked Vitamin C, their meat- and dairy-heavy diet supplied other vitamins. One of the doctors from Kazakhstan’s team, Amir Aldanazarov, reminded his Moscow colleagues that people in other rural areas of Kazakhstan also lacked Vitamin C, lived in hard conditions, but still weren’t as sick as people near the testing site:

“Moscow comrades explain away all the changes [in people’s health] with avitaminosis, even though they have no grounds for that. Some people in control areas suffer from avitaminosis too, but the difference in changes [in people’s health] is colossal. Moscow experts do not deny it. I find this statement not only incorrect but slanderous. Everyone knows that Kazakhstan’s population eats bread, meat, milk, dairy products, butter, cheese, kumys [horse milk], and so on in sufficient quantities. If there is any deficiency [in vitamins], it applies to control areas as well. Meanwhile, the difference in changes is colossal, as I said.”**

Kazakhstan’s doctors delivered 19 presentations describing their studies on the radioactivity of soil, confirmed radioactive isotopes in animals, and health sufferings of locals living next to the nuclear testing site. After listening, the Institute of Biophysics specialists concluded that locals’ main problems were brucellosis, tuberculosis, and parasite-related illnesses. After the conference in Moscow, the Soviet government pressured Kazakhstan’s Academy of Sciences to stop the medical expedition from further studies. Kazakhstan’s government did not have the power to stand up to its patrons in Moscow.

WHY COURAGE MATTERS

Medical professionals from Kazakhstan’s Institute of Regional Pathology made a conscious choice to undertake the expedition and document what they saw, undeterred by the repercussions they could face. They did it during the time when doctors in the Semipalatinsk region were prohibited from giving locals diagnosis that would suggest the impact of radiation. While the findings of the Institute of Regional Pathology were dismissed at the Moscow conference, they didn’t take the risk in vain. It is safe to presume the wealth of clinical data they generated mattered as it was shared with the Soviet and Kazakh leaders. Kazakhstan’s medical expedition carried out its work while diplomats from the Soviet Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom negotiated the potential ban on nuclear tests in Geneva. Thanks to an informal agreement between the three countries to pause tests during the negotiations, for a brief period between 1958 to 1961, the Semipalatinsk nuclear testing site remained quiet.

Starting in 1961, a facility in Semipalatinsk, disguised by the Soviet government under a misleading name of an Anti-Brucellosis Dispensary No. 4, surveyed 10,000 people living near the testing site and another 10,000 people in other areas as a “control” group. By 1963, thanks to the Partial Test Ban Treaty, the era of nuclear tests in the atmosphere, most harmful for the population’s health, ended. Still, for another three decades, underground nuclear tests continued at the Semipalatinsk nuclear testing site. Under pressure from a massive anti-nuclear movement Nevada-Semipalatinsk that united people across Kazakhstan against nuclear tests, the government of Kazakhstan finally shut down the site in 1991, a few months before the Soviet Union collapsed.

In 1998, a few years into Kazakhstan’s independence, the scientific findings of Kazakhstan’s Institute of Regional Pathology were declassified and made available to scholars. Today, this clinical data from the late 1950s is not only a valuable historical glimpse of what nuclear tests inflicted on people but a testament to the courage of scientists who were not afraid to record the truth.

*The author has the hardcopy of the memoir, which is in Russian. No copies exist in US libraries.

**Stenogramma konferentscii po obsledovaniiu radiologicheskoi obstanovki i sostoianiia zdorov’ia naseleniia v nekotoryh raionah Kazakhstana [Transcript of the conference on the survey of radiological conditions and population health in some areas of Kazakhstan], the conference took place on February 17, 18, and 20, 1961, at the Institute of Biophysics, USSR Academy of Medical Science, Moscow), Top Secret, declassified on Dec. 25, 1998, Central State Archive of Kazakh SSR, f. 79, o. 1c, d. 21.