On Tuesday, when US President Donald Trump announced his plan to spend $175 billion to create a “Golden Dome” shield over the United States that would intercept incoming missiles, he acknowledged that the idea was not new.

“We will truly be completing the job that President Reagan started 40 years ago,” he said. In reality, the United State has been seeking missile defense systems to shoot down incoming missiles for far longer, since the 1950s. Trump added that the Golden Dome would “forever [end] the missile threat to the American homeland. And the success rate is very close to 100%.”

Republicans have earmarked nearly $25 billion in a spending bill now making its way through Congress for the venture.

In the Oval Office announcement, Trump and the Republican lawmakers flanking him quickly switched from national security to pork barrel politics, name-checking the companies and states they said would be involved in building the system. That included Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, L3Harris and what Alaska Sen.

Dan Sullivan called the “new defense tech companies” — likely a nod to Elon Musk’s SpaceX along with Republican megadonor Peter Thiel’s Palantir and venture capital-backed startup Anduril — in Indiana, Georgia, Florida, and Alaska.

But few places in the United States have spent more time trying to come up with a way to shoot down incoming US-bound missiles (ie: the scenario that is the beginning of nuclear war) than Huntsville, Alabama, known as “the Pentagon of the South.”

First, a little background on why planning for Armageddon is a day job for many people in Huntsville, a modestly sized Appalachian town in northern Alabama that ranks among the top 10 defense contract spending locations nationwide.

*

The anchor of Huntsville’s military economy, the Redstone Arsenal, was built in 1941 and supplied troops with munitions during World War II. The city’s transformation into a technology and innovation hub dates back to Operation Paperclip, a secret post-war program that brought scientists from Nazi Germany to the US, believing they were in a competition with the Soviet Union to seize the experienced weapons-makers.

Among the most prominent of that group was Dr. Wernher von Braun — the title character of Dr. Strangelove is said to be partly based on him — who developed a German ballistic missile that was the first weapon of its kind and represented a turning point in the nature of warfare. The “flying bomb,” as it was called at the time, was shot toward cities in Allied countries, offering military planners “visions of a new type of warfare” that could be fought from hundreds of miles away “without needing to put one’s own soldiers or aircrews into harm’s way,” according to historian Dr. Charlie Hall.

After von Braun surrendered to the Allies, he went on to develop nuclear-armed ballistic missiles for the United States. But as soon as that new weapon was invented, a counter-weapon was then needed, and so by the 1950s the US was already working on ways to fend off incoming missiles, developing its first attempt at an interceptor, called Nike Zeus. Its project office was at Huntsville’s Redstone Arsenal.

The past is prologue, including for the arms industry, which publishes reams of press releases about ribbon-cuttings at new factories and breakthrough technology and job creation, but actually pops up with the same ideas in the same places time and again. Last week, the Huntsville-based Missile Defense Agency announced it was hosting a Golden Dome for America Industry Summit for companies to get in on the contracting bonanza. It will be held at the Von Braun Center in June.

*

That tangled town history is how engineer and disillusioned Vietnam War veteran Mike Schroer made his way to Huntsville. Using funds from the GI Bill, Schroer was able to get math and computer science degrees when he got out of the Navy. As is common for STEM graduates, military-industrial employment beckoned.

“Because of my military experience, military companies were the ones who wanted to hire me,” Schroer told me.

Schroer, who’s now retired, has been out of the defense business for about 25 years. He first worked first on the Patriot air defense system in the 1980s. It’s had many decades to prove its worth, and Schroer told me its shoot-down rate was unimpressive.

He pointed to the 1991 Gulf War. After the US Army initially claimed the Patriot had a near-perfect track record intercepting missiles, the military backed down its claims under scrutiny, and the Congressional Research Service would eventually report that the system had only one apparent success there.

No missile defense works as well as people claim.

In more recent times, the Patriot system reportedly failed to intercept any of the seven missiles fired on the Saudi city of Riyadh in 2018, and the results were deadly — one person was killed and two other wounded by missile fragments that fell from the sky. Even more recently, in Ukraine, the country’s army chief last year gave a sobering breakdown of Russian missiles the country has intercepted with its various missile defense systems, with rates sometimes in the single digits depending on missile type. And just earlier this month, Israel’s missile defense systems failed to shoot down a ballistic missile from Yemen that hit near the Ben Gurion International Airport.

“One missile, not a batch of missiles to saturate the air defense, just one, and it got through the Iron Dome and several other air defense systems,” Schroer said. “They supposedly have a multilayer defense system with all their systems combined. But that sure doesn’t make building the Golden Dome look very feasible.”

While intercepting some missiles sometimes sounds better than none and never, that calculus becomes fraught when the US is preparing for missiles of the nuclear-armed type — a missile that exits the atmosphere and travels across the globe, not just a few hundred miles. In order for it to actually stave off nuclear war, such a hypothetical missile shield would have to work “perfectly, perhaps the first and only time it’s ever used,” longtime nuclear policy analyst Joe Cirincione explained.

*

“No missile defense works as well as people claim,” said Cirincione, who traveled to Huntsville in the 1990s to probe the Patriot missile system on behalf of the House Committee on Government Operations, where he was a chief investigator on defense systems.

Schroer said not to trust industry claims about how often they intercept missiles in test scenarios, which involve militaries knowing details of the target missile and launch time in advance and scrubbing the test when the weather isn’t optimal. When he began working on “Star Wars,” officially called the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), in 1986, “it was common knowledge in the business that the target was enhanced to make the intercept successful,” according to Schroer. For example, in 1993 a New York Times reporter revealed that the army had staged a 1984 missile defense test by planting a remote-controlled explosive on the target missile so that it would blow up whether or not the interceptor actually hit it.

Both that history and the actual performance of missile defense systems in combat zones are what lead Schroer and Cirincione to oppose a “Golden Dome” as wishful thinking, not to mention that countermeasures could very well disable it, like a volley of decoys to overwhelm the system or weapons that target the constellations of satellites that would be needed to support a missile shield. (Cirincione’s words in a recent op-ed: “National missile defense advocates live in a world of magic and make-believe. Fantasy replaces science, assertions replace facts, and cartoon weapons replace real capabilities.”)

And that’s not to mention the cost for such a fantastical system. Merely replicating Israel’s Iron Dome over the US — multiplying it out to cover nearly four million square miles — would require 24,000 Iron Dome batteries “at $100 million a pop,” Cirincione said. And that’s for a system that’s made for an easier task, intercepting rudimentary and relatively slow-moving missiles from militants, not nuclear-armed ballistic missiles shot from across the globe coming toward the US in a matter of minutes.

*

Schroer said engineers, with their noses deep in resolving each tiny technical step toward achieving a hypothetical missile shield, can engage in a myopia that misses the forest for the trees. As he sees it, it’s the weapons industry shielding itself from reality by magical thinking, more so than the diplomats or activists who seek to negotiate a world with fewer or no nuclear weapons.

Here’s what Schroer said about how missile defense engineers do their jobs:

“When I was working on the SDI program we were always looking to improve the technology to overcome the current technology shortfalls. That might be sensor technology, computer power, software algorithms, power sources. The challenge to innovate and build is what makes scientists and engineers tick. And in our current system, the fact that you need a job to keep a roof over your head and food on the table also brings you into work every day.

But as you wade into the development of these very complex systems, you start to realize you bump up against physical limits. As these systems get more and more complex, each component of the system has to become more and more reliable for the overall reliability of the system to be useful. Then you have to remember that you are building a weapons system and the enemy has a say in the exchange. They devise equipment and tactical countermeasures. At some point you may reach a point of technological or financial inviability.”

If an engineer doesn’t “step back and take a look at the big picture,” Schroer said, then their “day-to-say search to innovate and fix that next technical challenge” will keep them plodding ahead.

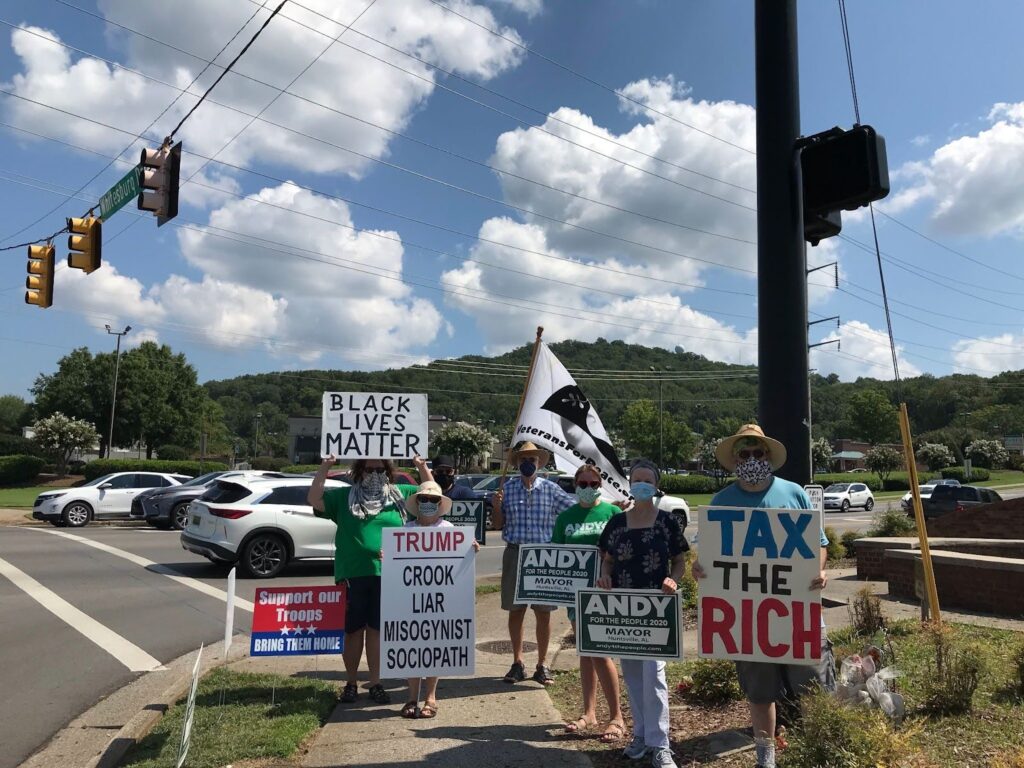

But not so for Schroer. He left the industry for a more ordinary job in telecommunications, opting for a technology that reliably served people in their day-to-day lives. And nowadays he spends his retirement as a regular at the weekly Peace Corner protest in Huntsville, waving a Veterans for Peace sign emblazoned with a dove.