Shortly after news broke of the appointment, Sheriff Brad Coe texted his friend, Tom Homan. Homan had just been named the “border czar” for the incoming Trump administration, and Coe, the sheriff in Kinney County, Texas, wanted his fellow Border Patrol alum to know he is ready to support the president-elect’s efforts.

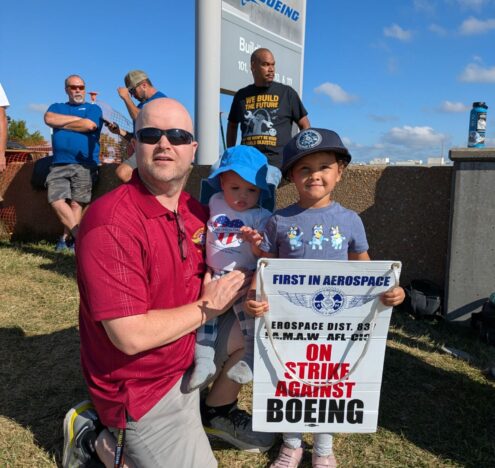

Specifically, Coe tells Inkstick that he is reaching out to sheriffs across Texas and Oklahoma and compiling a list of those who might be interested in the 287(g) program. Through this initiative, sheriffs can partner with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to enforce immigration laws and detain and interrogate people they suspect are not legal citizens of the US. Once he shares this list with Homan, Coe says, they can “get the train rocking and rolling.”

This collaboration indicates how sheriffs may partner with the Trump administration to enact the president-elect’s immigration policy, including plans like “the largest deportation operation in American history.” It’s also the latest evolution of Coe’s longtime focus on immigration.

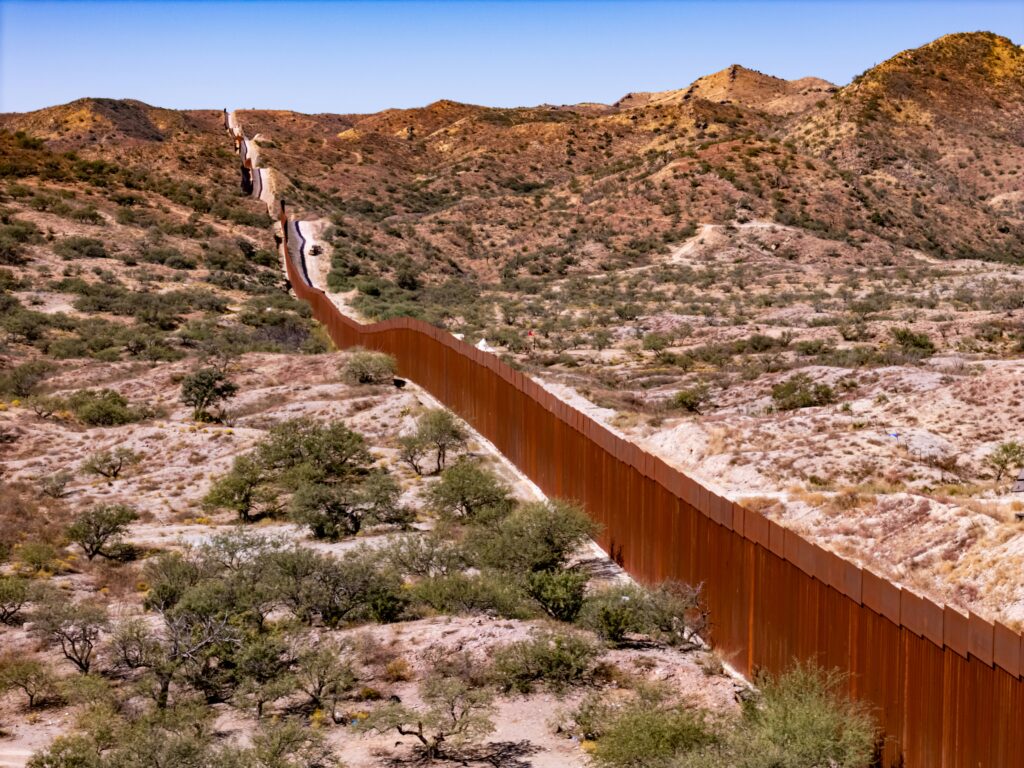

Kinney County is located in far southwest Texas, roughly half an hour from the border, and in late summer 2024, Coe sued President Joe Biden’s administration alongside Michael Vickers, a nearby rancher and militia leader. Their suit argued that Biden’s policies created a “massive flood of illegal entries by foreign nationals from around the world.” In early 2024, the number of people crossing the border did indeed reach record levels, and shortly thereafter, the president asked Congress to give him the power to shut down the border.

That said, experts argue this lawsuit was mostly for show.

“Nuisance Lawsuits”

Coe himself says the case will likely be dropped soon, especially with Trump in office. Jessica Pishko, a lawyer and journalist who has been covering sheriffs and law enforcement for more than a decade, called it one of many “nuisance lawsuits” commonly filed by conservative actors and their allies during the Biden years.

“I look at it in the context of the overall strategy,” she says, “Most of the time, the lawsuits don’t go anywhere. They just like doing it, and a lot of it is to get attention to their issues.”

Now, interviews with people on both sides of the political spectrum unearth how the tactical and legal operations of that “overall strategy” could change in Trump’s upcoming term. “All these sheriffs and agencies have been asking for Trump, but there’s not much that they didn’t get under Biden,” Pisho explains, except for “permission to do whatever.”

Militias Gear Up

Right before he broke his leg, militia leader Samuel Hall was tracking a man through his night vision goggles. The figure had just crossed a river in Eagle Pass, Texas, roughly an hour from the Mexican border, and Hall thought the man had two small children with him.

He started to make his way down a cliff, but he fell. The resulting injury required surgery, sidelining him for 13 weeks. Hall, however, isn’t complaining: He was trying to do exactly what he and his militia, Patriots for America, set out to do.

“Our number one goal is to identify children that are being trafficked by the cartel for nefarious purposes such as organ harvesting, sex trafficking, labor, et cetera,” Hall tells Inkstick. “We’re there to support law enforcement and deter illegal immigration.”

By definition, a militia is an armed group staffed by the citizenry. The history of the United States — and of Texas in particular — is rife with such groups. For example, the Texas Rangers began as a militia, often collaborating with civilians to remove Native Americans from West Texas and terrorize Mexican-Americans.

In recent years, militias across the country have participated in plots to kidnap political leaders and storm the US Capitol, while on the Southern border, many groups have spread conspiracy theories and, in some cases, detained migrants.

Unreliable Data

It’s unclear how many militia groups exist as of now, but some estimates put the number in the hundreds. Further, many of these groups share Hall’s focus on children, often filling Facebook and other social media platforms with photos and videos of child migrants. Attorneys and researchers argue that unreliable or unclear immigration data arguably makes these groups more influential.

According to data recently released by the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE, more than 400,000 non-citizens with criminal convictions are on ICE’s “non-detained” docket — including more than 13,000 people convicted of homicide. However, the department pointed out that this data set includes people who are “under the jurisdiction or currently incarcerated by federal, state, or local law enforcement partners.”

At the same time, reliable human trafficking data — especially data sorted by country — is near impossible to come by. US Customs and Border Protection data from 2023 revealed more than 137,000 run-ins with unaccompanied children in 2023, a decrease of nearly 10 percentage points from the previous year.

In an interview with Inkstick, Hall admitted the “militia” label has harmed his group’s reputation, though he has no plans to go by anything different. He says he condemns white supremacy and is eager to distance himself from anyone or any group that espouses that ideology. That’s just one of the reasons he says Patriots for America conducts background checks on anyone who expresses interest in joining their ranks (and, he adds, somewhere between 80 and 90% of potential applicants do not consent to a background check, thus ending any chance they have of joining his group).

Armed Patrols

For the last three years, the militia Hall founded has been going on “rotations” ranging from seven to 15 days at a time. Making deals with private landowners near the Texas-Mexico border, Hall and co. patrol the area armed with rifles. When encountering suspected migrants, they offer them food or snacks. Then they start asking questions.

“Whereas right now, we do what we want, when we want.” – Samuel Hall

If they think the children they meet are being trafficked, they call local law enforcement — but that’s about all they can do. Migrants may suspect Hall and his group are members of law enforcement, or, as The Intercept has pointed out, they may be simply terrified, not sure what to do. But Hall emphasizes, “We don’t arrest and we don’t detain.” They also, he says, have never fired a shot.

When talking about background checks, Hall noted: “It only takes one guy who has these delusions of grandeur to go down there with an itchy trigger finger and do something stupid.”

“We Do What We Want”

Instead of personally arresting migrants, Patriots for America shares intel with sheriffs like Coe, whom Hall calls “a good friend.” While they’ve talked about more formal collaborations in the past, nothing has come to fruition just yet.

“If they deputize us, and if they give us more authority, obviously we’d be open to that, but we’d still have to talk about that,” Hall says. “We do operate more freely as a constitutional militia, whereas if we were deputized, we’d be under the authority of a sheriff or whomever. Whereas right now, we do what we want, when we want.”

Coe tells Inkstick that, while a formal relationship with Hall’s militia is unlikely, they do talk regularly. He likes to “keep tabs” on Patriots for America, he says (“That way we don’t suffer from friendly fire, so to speak.”)

These relationships are pivotal to understanding the broader ecosystem that, after inauguration day, will have more power in DC. For instance, Hall frequently appears in the media, either as a Fox News guest or an op-ed writer for Newsweek. (This, Pishko says, is often the greatest impact of militias: Their power as messengers, either through social media or on the president’s favorite television channels.)

“Hope It All Changes”

Further, Hall is now mere text messages away from Trump’s border czar, and in recent weeks, experts have pointed out the open lines of communication many militias have already established with forces like Border Patrol.

As for what Hall hopes changes during Trump’s second administration?

“Everything,” he says. “I hope it’s all different. Because there’s nothing that’s happening right now that’s in any way effective.”

That ultimately means legislative change (as he indicated in his Newsweek opinion piece). Trump has promised as much, including a rerun of many of his first administration’s policies.

But going even further — as promised with Trump’s deportation plans — is, as one expert says, “extremely unrealistic.”

46 Years

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick is a lawyer, not a mathematician. But it wasn’t hard for him to run the numbers.

ICE was at the apex of its power when President Barack Obama was in office and authorities deported roughly 383,000 people each year. Trump’s annual average neared 300,000. Thus, if Trump implemented the same approach as his first term, it would take about 46 years to reach his preferred deportation total of 11 million people.

If he matched Obama’s numbers, it would take about 29 years.

“We’re talking about a population distributed across the entire country in different communities, varied socioeconomic groups,” Reichlin-Melnick says. “The idea that the US government could round up and deport 11 million people is extremely unrealistic.”

That’s not to say the president-elect won’t try, he adds. But attempting a program at that scale would require a massive infusion of resources, including boatloads of money.

Reichlin-Melnick is a senior fellow at the American Immigration Council, and his team recently analyzed the cost of a mass deportation operation. Carrying out one million deportations a year (an unheard-of number) would cost, on average, $88 billion annually.

“That,” the lawyer points out, “is more than the entire budget of the Department of Homeland Security.”

Lack of Manpower

Money isn’t the only obstacle — there’s also a severe lack of manpower. 287(g) agreements could help make a dent in that issue, and Reichlin-Melnick says it is “very likely” these agreements will become even more common. Still, he says many sheriff’s offices don’t want to participate in the program (“They don’t want to spend their days going out and finding people.”) And those that do may just be adding to the deportation plan’s biggest problem: the bottleneck in immigration court.

As of early December, there are more than 3.7 million pending cases in immigration court. Reichlin-Melnick says over half of those cases involve people who migrated in the last couple of years. There simply aren’t enough judges to process such a high volume in a timely fashion. “There’s a real chance people arrested in the early days of the Trump administration won’t get a hearing until after Trump has lost office,” the attorney says.

What’s more, some countries — Venezuela, for instance — do not accept deportees, and a new agreement would likely involve the removal of some sanctions.

For her part, Pishko says, “One big problem will be relationships with other countries. ‘Remain in Mexico’ is not very popular in Mexico, because it creates camps on the border no one really likes.”

“Detention Assets”

In interviews since his appointment, Tom Homan has admitted he needs more resources to carry out the president-elect’s plans.

“What people don’t understand is we can’t just put [them on] a plane,” he has said, according to ABC News. “There’s a process we have to go through. You have to contact the country, they have to agree to accept them, then they got to send you travel documents. And that takes several days to several weeks. So we need detention assets.”

By “assets,” he means beds, facilities, and people. County jails may help solve some of the facilities issues, and as for personnel, Trump has said the military will play a role in his deportation plans.

“What people don’t understand is we can’t just put [them on] a plane.” – Tom Homan

While the Posse Comitatus Act prohibits the armed forces from participating in domestic law enforcement, Ryan Burke — a professor at the US Air Force Academy, recently told Reuters that Trump’s attempts to use the military for this purpose “probably won’t face a whole lot of successful challenges.” Other experts echoed this sentiment, telling the news wire agency that the military can indeed support Trump’s efforts, provided they do not interact with suspects.

“When the military comes to assist at the US-Mexico border, they’re typically doing auxiliary support,” Pishko explains. “They’re setting up camps, bringing in comms equipment — basically providing infrastructure.”

“Mass Surveillance”

If such involvement faces challenges in court, Trump and his allies will have the backing of legal organizations like the Immigration Reform Law Institute, which has filed many suits similar to the one filed by Coe and Vickers.

“We anticipate filing many briefs defending Trump’s policies when they are attacked in court by anti-borders activist groups,” Chris Hajec, the organization’s director of litigation, tells Inkstick.

The military needs land to provide any “auxiliary support,” and Texas has indicated that it is willing to help on that front. They also need what Reichlin-Melnick calls “a police state — mass surveillance unlike anything we have seen in this country’s history.”

“All Very Bad”

Both Reichlin-Melnick and Pishko say that the Trump administration often conflates enforcement at the border with immigration law writ large. There are many people — more than one million, as of a year ago — who have been ordered deported yet remain in the US. This, Reichlin-Melnick says, “is the most vulnerable population.”

Pishko, meanwhile, says that no matter what happens — no matter how close Trump can realistically get to his stated goal — it’s always the people who were already vulnerable who suffer the most. President Biden funneled billions to law enforcement during his administration, so it’s likely police departments and county jails receive less federal funding during the upcoming Trump years. Even still, there could be core differences between the two administrations — the relaxing of standards of care, for instance, or the loosening of guidelines surrounding use of force.

“It’s all very bad for individuals who get swept up in this,” Pishko says, “They’re very likely to experience long delays and overcrowded, unsafe facilities where people get sick and die.”

It is, she continues, “a system of randomness that’s increasingly unpleasant.”