It’s been one year. One year since we last saw our friends and family without masks, without fear, without COVID. And almost one year since my family struggled to save my father from the pandemic that ripped through our country.

I remember the morbidly exciting uncertainty at the start of this pandemic. I remember feeling optimistic. I remember thinking, naively, that this would bolster our need for scientific understanding and multilateral cooperation. I’m no Trump supporter, but a part of me still hoped that the administration would at least step aside and let scientists and communicators do their thing.

Then, like a snowball, things started going downhill. I was stuck at home, and doing my best to keep my optimistic outlook. I remember turning to my father and searching his face for a sign of comfort and reassurance. My family and I hail from El Salvador, a country famous in America for pupusas, eye-catching Spanish slang, and MS-13. El Salvador suffered a civil war throughout the latter half of the 20th century, and both of my parents were survivors. Of the two, my father was the one that saw the conflict firsthand, as a child watching guerilla groups exchange gunfire with the army as air raids occurred over his head. An experience so grim that it pushed some of his family to flee to Sweden — but not him. Instead, he came to the United States.

Now, in the midst of another crisis, I could see his mind racing to come up with solutions, thinking about what would come next. It was only March, but neither of us believed Mr. Trump’s claims that the virus would disappear by June. He and I didn’t have a good relationship until recently, so I saw our shared determination to get through this as an opportunity to further our father-son bond.

Early on, we were beaten to the toilet paper and hand sanitizer, but we managed to stock up on food and water just in case. To put it dramatically, we were not going to depend solely on what the official channels were telling us. At the same time, I was wary of my father’s sudden distrust in the media, he had taken a particular interest in the vein of predictive programming conspiracies, and the latest culprit in his eyes was The Economist magazine with its cryptic and bizarre cover art. I tried to channel his preparation fervor, instead, into discussions of science, communication and strategy. That was my world.

Now, in the midst of another crisis, I could see his mind racing to come up with solutions, thinking about what would come next. It was only March, but neither of us believed Mr. Trump’s claims that the virus would disappear by June.

I was brought to the USA as a two-year-old, and now I am a naturalized citizen. All I have known is a life full of privilege and comfort, in comparison to my cultural peers who are undocumented. I dealt with depression two years prior to the pandemic and, ironically, it gave me a glimmer of hope. Because I had managed to fight it off, I thought I would be better equipped to #StayInside. But this was my first external crisis. All my previous experiences with external threats at this level had been in policy conversations.

In high school, I started working on nuclear weapons issues through organizations like Nuclear Free Schools and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization Youth Group. Today, I champion science diplomacy and search for ways to make the bridge between scientific data and policy shorter and stronger. I am first and foremost an aspiring nuclear policy expert, but the current challenge contains echoes of those we face on the nuclear front. These threats to humanity require teamwork. If one player drops the ball, we all suffer. So, like the information addict that I am, I decided to do a deep dive on COVID, in the hopes of better protecting my family.

In April, I attended an online webinar with South Korea’s CDC to learn about their experience with the pandemic. I used their testimony to gauge the American response. Even with proper contextualization, it was heartbreaking to see how unprepared the US was. The same was true when I compared the US to El Salvador. In my country of origin the president urged people to shut themselves at home, while the president of the country I call home pushed hydroxychloroquine as a miracle remedy. A drug my family knows better than most. It was the same drug that gave my mother severe side effects after using it for only a few days to treat her lupus.

In May, my grandfather succumbed to COVID in El Salvador and it devastated us all. I renewed my efforts to read as much as I could about the virus, and reached out to some incredible experts. I feared for my mother who is at-risk thanks to lupus. Even before the pandemic, the condition meant that extreme stress could leave her hospitalized for a week. My grandfather’s death, her father, was the latest threat to her health.

We remembered the footage from our family in El Salvador showing his last days on this earth, and we saw parallel trends with the collapse of Salvadoran hospitals in our domestic American hospitals. At the time, New York City was racked with an ever-expanding number of cases. Little did we know that this would eventually lead to the need for freezer trucks to store America’s dead. At some point, the Trump administration sent ventilators to El Salvador as a form of diplomacy.

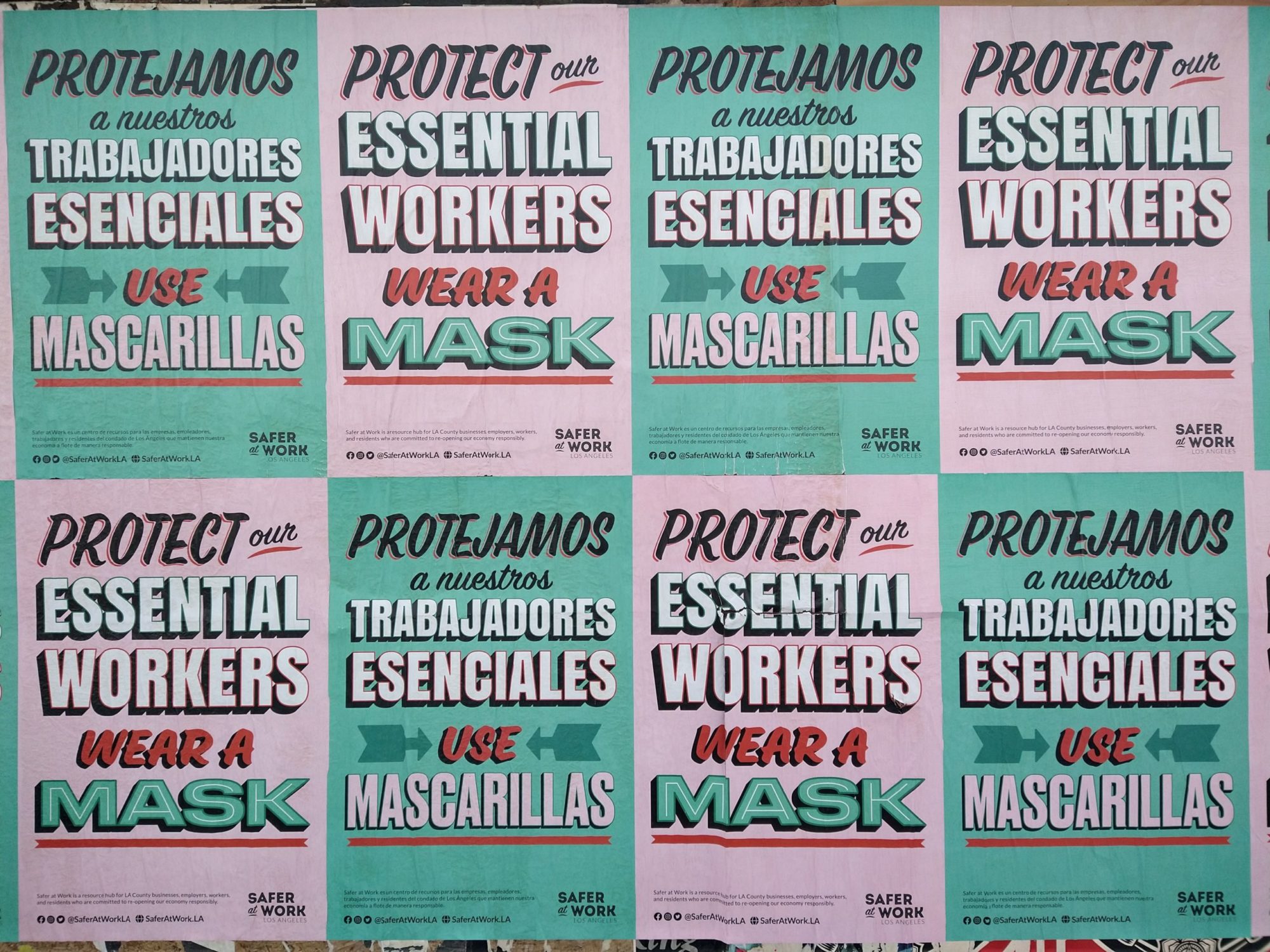

My family and I looked towards our governor and mayor for hope as they addressed us every night and day. We received word that some of our friends’ sisters and brothers died from COVID. I felt like there was a shadow lurking outside my window, peering in. My father was no anti-masker, in fact, he laughed at the people who called mask-wearing “suppression;” however, his comments and subsequent dismissal of COVID-coverage as nothing more than yellow journalism was deeply concerning.

Fast forward to July. My father is a mechanic and has been working since the pandemic began. He has always been uncomfortable with wearing a mask, especially in the bright sun where temperatures can reach the 90s. The week of Independence Day, he came home looking much more tired than usual, almost zombie-like, and he complained of back pain, almost as if he had taken a bullet to the kidney. That Wednesday night, my mother woke up and noticed he had a fever, which continued for the next three days. That Friday night we locked him in my parent’s room and proceeded with the mandatory 14-day isolation period. I remember jumping into action with the mentality that our house would run as a makeshift field clinic. We stocked up on cleaning chemicals, food, vitamins, etc. to give ourselves hope and a fighting chance. All while following the testimonies and medical advice of doctor friends and family in the US and abroad. We understood that American health infrastructure is supposed to be better than El Salvador’s — California had not gone full New York in terms of collapse just yet, that would come in December, and boy was it terrifying — but we were still very much traumatized by my grandfather’s death, and Trump’s words of wisdom were doing us no favors.

It took my father three days to secure a test. Then it took another two weeks to get the results. In total, it took 17 days from the time he first demonstrated symptoms to confirm he had COVID. In that time frame, we borrowed a pulse oximeter, purchased a new in-ear thermometer, and installed a remote camera in the bedroom to monitor the progression of his symptoms, since we had trouble getting back word from his doctor and were reluctant to turn him over to the ER. He reached a near-critical point during day nine. That night my mother went in, decked out in makeshift PPE, to prevent his fever spike from becoming a full-on convulsion. She was inside the room for 30-45 minutes, as I helplessly watched with my dog from my phone in my bedroom next door. By the time the test came back, my father had already been out of isolation for a full day. Had my mother and I not treated it seriously, my father would probably be in a worse situation, and we don’t even want to think what the hospital route might have looked like.

Now it is March 2021. America has a new president, a slew of new executive orders, and a COVID relief bill on the way. My family is back into the monotonous slog of pandemic life. My father is back at work, my mother and I remain at home exploring new hobbies while balancing our respective responsibilities. At the moment, we’re COVID free, but still more of our friends and family have succumbed to the virus, with some not likely to be seen again. I keep studying and learning to protect my family, but the conversations I have with others in my Spanish-speaking community are disheartening. I would be willing to wager that more members of my immediate Spanish-speaking community have utilized the term “China Flu” than have read about protective measures. Sure, Telemundo and Univision have done their best to keep people up to date, providing live translations and amping up coverage, but they could hardly compete with the misinformation spread daily from a negligent government during the worst parts of this crisis. And while I’ve done my best to teach my family, this is information that I’m not confident will spread as effectively as COVID. I can continue to learn and inform others in my community, but I can’t shake the feeling that so much of this is too little too late. If a nuclear weapon were to detonate in Los Angeles, my expertise would not help anyone after the fact.

The research, the education, the myth-busting all has to come beforehand. That’s why I work closely with nuclear grassroots groups and other NGOs every day. The pandemic has taught me that when it comes to addressing monumental challenges, pressure needs to come from both above and below — akin to an orbital wave. I know what grassroots change can do, and I’ve heard of the trickle-down approach, but the truth is, one cannot exist without the other. Over the past year, we have seen firsthand how disinformation from those in positions of power can undermine the best-intentioned experts, even when the truth of a crisis is right before people’s eyes.

Cristopher Cruz, is a Santa Monica College student and is also the Co-founder of Nuclear Free Schools, a high school project aimed at informing students of all ages about nuclear issues. He is also a Communications Coordinator for the CTBTO Youth Group. When not vouching for nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation, he can be found roaming museums and parks or watching Godzilla movies. You can follow him on twitter at @CCruzColorado.