It’s the two little girls that I keep thinking about.

One night in Mariupol I was eating dinner in a basement tavern when I saw a sight familiar to modern-day parents the world over. Two cute little girls, obviously sisters, were making goofy selfies with their phones. It’s the sort of local color I like to capture in photos when I travel, but the lighting wasn’t good, the girls were moving quickly, and I was anxious to dig into my food. I can’t help but wonder where they are now or if they are even still alive. I can’t help but wish that I had taken that photo so the world could see what life was really like in Mariupol prior to the death and destruction that President Vladimir Putin’s forces unleashed while “liberating” a place that didn’t need to be.

Russia has made a series of announcements about its plans for the devastated city of Mariupol. They include possibly leveling the steelworks that was the city’s major source of employment and turning Mariupol into a tourist destination. The Governor of the St. Petersburg region said that his region stands ready to help restore and rebuild Mariupol. One would think Mariupol, a city the size of Miami, had been hit by a devastating hurricane.

CIVIC LIFE IN MARIUPOL BEFORE THE SIEGE

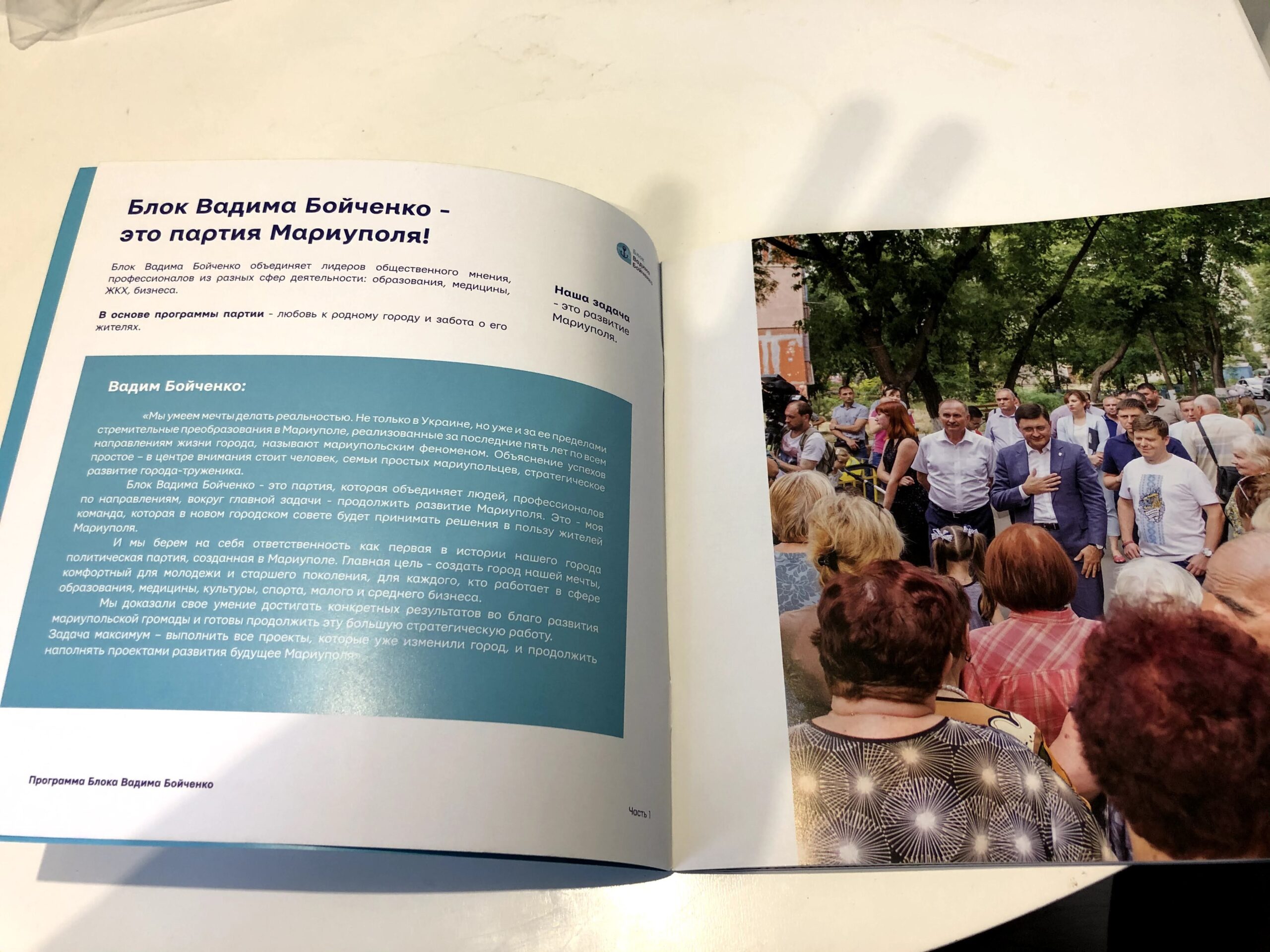

Reading these plans may make one think that Mariupol was a place that had not existed before Russian forces “liberated” it. I was in Mariupol to observe its local elections in the fall of 2020. It was Ukraine’s first nationwide elections for local offices. The favored candidate was acting Mayor Vadym Boychenko. His team presented us with a guidebook about their plan to improve life in Mariupol up until 2025. Their plans included $53 million to be spent on housing, more parks and recreation areas, port expansion, etc. Their plans were not without controversy. Small businesses complained that it was too difficult for them to survive in a local economy that was dominated by wealthy interests. There was, however, lively debate and discussion.

I witnessed one city council candidate meet with voters in the courtyard of the apartment building I was staying in. We talked with a prominent local environmental activist and politician who had once been considered a mayoral prospect. He had become a local hero of sorts when he took on Rinat Akhmetov, the richest man in Ukraine and Mariupol’s largest employer, and successfully demanded that he clean up the air pollution emanating from the Azovstal steelworks that he owned. Boychenko sat in for tough questioning from reporters even while quarantining at home due to possible COVID exposure, during which time he showed off his cat to the voters.

On Election Day itself — Oct. 25, 2020 — and during the tabulation process, local activists watched intently and sometimes sparred with elections commission members, but it was generally amicable, and nobody ever got arrested. I felt, in short, like I had observed a somewhat imperfect, but fairly typical local election of a sort that was unknown in Ukraine not all that long ago. Democracy at the grassroots level was taking place in Mariupol and in Ukraine as a whole.

More often though I saw people just having fun — couples, parents with kids struggling to bicycle, or guys flying a drone. What’s happened to them all?

The Kremlin is doing its best to flush all of this down a memory hole. In Russian propaganda, Mariupol was a fascist mini-state run by a neo-Nazi militia group that needed to be “rescued.” Yet, I never once saw anything like that anywhere in the city. Most ridiculous of all, the Russians of Mariupol were supposedly being persecuted by Ukrainians when in fact the entire city from the political establishment spoke Russian on a daily basis. Yet, nothing is ever said about the city’s Greek heritage and its sizable ethnic Greek minority because it doesn’t fit the propaganda narrative. In fact, Mariupol was founded by Greeks from Crimea during the time of Catherine the Great.

THE ONES I THINK ABOUT

There are many others that I think about. There was the teenage boy who, taking COVID into consideration, politely asked if he could get into the elevator with me and then got all excited when he realized that I was a native English speaker and wanted to practice. What became of the girl at a nearby coffee stand who always served me coffee with a smile or the hostess at the restaurant who always snapped to attention when I walked in the door? There was that comedic moment when I went into a drug store, and the clerk behind the register tried to twist my arm to sign-up for the store’s discount club even after I made it clear that I was a visiting foreigner. What happened to her?

I was in Mariupol for only about five weeks. Nevertheless, my work took me to all parts of the city, and I met people from all walks of life. I lived in an apartment and shopped at the same supermarkets as the locals. That by itself was a wonder. On my first visit to Ukraine in 1994, I could barely find a good restaurant in Kyiv. On the other hand, Mariupol, a much smaller city, had large supermarkets that were as well-stocked as the most high-end American food emporiums. However, after the siege, there were photos and videos of the Russian military distributing food aid to Mariupol residents.

For me, the places that we hear about on the news are not just places on a map. I was lying in bed on Saturday morning, Mar. 12, 2022, and turned on the TV, and the first words that I heard were that the town of Vulnuvokha had been destroyed. I had been there several times only a year and a half before. I had several meetings in a nice local cafe. Stariy Krim, where there is now a mass grave, is a village where I had watched a campaign rally. The village of Manhush, another mass grave site, is a place where I observed voting on Election Day.

The maternity clinic in Mariupol that was bombed was just a short walk from the apartment that I rented. I walked past it several times while out getting exercise. It didn’t look like much, and I hardly figured that it would soon be the scene of a high-profile war crime. The Mariupol drama theater, the scene of another high-profile war crime, was a place I went by at least once a day. There was an excellent Georgian restaurant on the theater grounds where I had many a fine lunch and dinner. My colleague and I had dinner at a fancy restaurant across from the theater and had the place mostly to ourselves until the theater crowd let out and streamed across the street to fill the tables up.

The drama theater was where we watched a struggling candidate try to gain attention and hand-out campaign swag to passers-by while teenage bicyclists and skateboarders whizzed barely dodging the majestic fountains. There were pony rides for children that went along the perimeter of the theater’s park.

A nice couple in their 30s owned the apartment I rented. I can’t help but wonder if they are still alive now. The apartment overlooked the city’s Freedom Square. The square was created after the fighting in 2015 to honor those who were killed defending Mariupol and as a call for peace. The square was lined with sculptures of doves for peace perched high on poles, with one dove for each of Ukraine’s 24 oblasts and a bell that was a gift from the city of Hiroshima. There was a cascading fountain that changed colors at night accompanied by various recorded music or a live concert. I could look out and see small political rallies.

More often though I saw people just having fun — couples, parents with kids struggling to bicycle, or guys flying a drone. I had to quarantine due to possible COVID exposure, which gave me plenty of time to take it all in. What’s happened to them all?

POST-SIEGE

Western media accounts of the murder of Mariupol fail to capture the victim’s life. Mariupol was a city much like any city in a democratic society. The people had their political differences, but they settled them at the ballot box and occasionally in the media. The system was not perfect, but people had a say in it. Now decisions for Mariupol are being made in Moscow.

One edict from Moscow seems small but is significant. Ukraine has struggled to convert Soviet-era government-run housing blocks into modern resident-operated entities such as condominiums. According to Telegram channels that report on Mariupol, the new “government” of Mariupol, as one of its first actions, decreed that from now on all housing boards, such as condominium boards, are illegal. Decisions on how all of Mariupol’s destroyed housing will be operated will be made in Moscow. This is how Putin plans to “de-Nazify” the city.

Every day as I headed for the center of town just before the drama theater there was always an old man dressed up like a jester performing assorted stunts for the passers-by. He was known as “Uncle Vova,” a fixture of Mariupol. Legend has it that he had worked for the government and when he retired, he just wanted to spend his time bringing joy to people. He got his share of tips, but one got the feeling watching him that he would have gladly done it if nobody had ever tipped him.

He survived the siege and is back on his now devastated street corner. He has a very difficult job ahead of him.

All photos are taken by the author in October 2020.