Sept. 12, 2001 was the first day of my politicization. You see, before that I had no reason to be afraid. I was born in Iran and came to the United States when I was about 4 years old. I had been diagnosed with Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis in the early 90s after waking up one morning and simply not being able to walk or barely even move at all. My mama brought me here with $11, and it was by the grace of God, and the help of our family and friends that we had made it so far with so little.

When I first started school, I was placed in a fully exclusive special education school because I couldn’t walk and I didn’t speak English. They couldn’t understand me, so they assumed I couldn’t understand anything at all. But I understood — I knew I wasn’t in the right place. So I guess even back then, I knew that something was out of place; that assumptions were being made about me based on the brownness of my skin, the hairiness of my arms, and the language I chose to express myself in. But it wasn’t until 2001 that my otherness truly revealed itself.

I am now an educator, and use my teaching as a tool of activism. I believe that a better world is possible and that community is what will help us to get there.

On 9/11, I woke up a high school freshman in our tiny apartment and watched the news with my mom as I got ready for school. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I had never seen such a war zone, despite being born in the midst of the Iran–Iraq war. I was scared. I honestly don’t even know why I went to school, but I remember thinking that if New York was hit, Los Angeles could be next. Not only that, but I was just there. We had just taken our 8th grade trip to New York in April 2001, and I loved it so much I couldn’t wait to go back. I could imagine being a student at NYU, a Broadway season ticket holder, a night owl who could actually have something fun to do in the middle of the night. I had bought an “I <3 NY” shirt while I was there and I truly meant it. I truly, deeply LOVED New York.

And then, it all changed in the blink of an eye. I was so incredibly sad. As a highly sensitive person and an empath, I feel things on such a deep level, and the omnipresent heartache around every corner was just so much. I think there was a rumor that someone’s dad was in one of the buildings. We watched the news in every class, all day.

I don’t remember when this thought set in, but I know it did. I started thinking:

“Oh shit, they were Muslim.”

“They had names like mine.”

“The last time an attack like this happened, everyone remotely similar was rounded up and sent to internment camps. That means I could be next. My family might be next.”

I don’t know if it was paranoia or if other people really did start looking at me differently, but for the first time in my memory, I truly realized how not white I actually was. I mean, I had spent a lot of years trying to figure out why I had to mark white on standardized tests. Turns out, Iranians have a complicated relationship with whiteness. When it comes to racial/ethnic metrics, there is very rarely a box to mark “Middle Eastern” and when you look at the given notes, it tells you that Iranians are Caucasian, and therefore, considered white. After 9/11, I began to realize that I wasn’t really white, and for the first time, felt the sting of so many eyes on my olive brown skin.

So, by Sept. 12, 2001, I had gone from an innocent, boy-band-loving freshman to a politicized, anxious young brown woman who might be considered a threat and was, therefore, a target. And so with that, I started the new year by going to my first protest. I wanted to stand up for myself and for others who looked and felt like me. President George W. Bush and the Global War on Terror (GWOT) were affecting thousands of people in lands far away that had nothing to do with what had happened in New York on that tragic day. We the people did not ask for this war, and there were so many ways that those war funds could have been spent in helping our communities. The protest also marks the start of my activism work with South Bay Youth for Peace and Justice (SBYPJ), and in hindsight where I really began coming into my own path in life.

AN ACTIVIST IS BORN

Fast forward through high school and college, and being an activist became a natural part of my identity. I marched at anti-war protests, chanting in community about how the people united would never be defeated. I joined my friends from SBYPJ and created a Peace Club on my high school campus. We started an annual Peace Camp in the San Gabriel Mountains where we wrote poetry and had drum circles and learned history and shared our hopes and dreams for a better future. We wrote and printed and distributed a magazine called “The Activist” on MySpace where we shared important news and information with people our age. We asked for military representatives to leave our campuses, we did demonstrations about the number of lives that had been lost since the start of the war on the lawns of our schools campuses, and we stood on street corners with giant papier-mache puppets and candles on Friday nights praying together for an end to the senseless and seemingly never ending war.

Twenty years later, the significance of 9/11 and the day after remain a part of my consciousness. The GWOT and the policies that followed have had a direct impact on who I am, what I stand for, and how I show up for others. My heart breaks for the ways this one moment has shattered so many lives, both of the victims of the tragedy itself, as well as the brown people who have been targets of Islamophobia in the aftermath. To this day, airports make me nervous because I know I will be scrutinized. The glare of someone’s eyes as my mom and I speak Farsi makes me on edge because I wonder what they are thinking about us. The way movies and TV shows perpetuate the stereotype of the Muslim terrorist makes me angry. The villainization of Iran and my people, to the point in which humanitarian efforts are not even being extended during the midst of the deadliest pandemic in decades, is just crushing.

PAVING THE WAY FORWARD

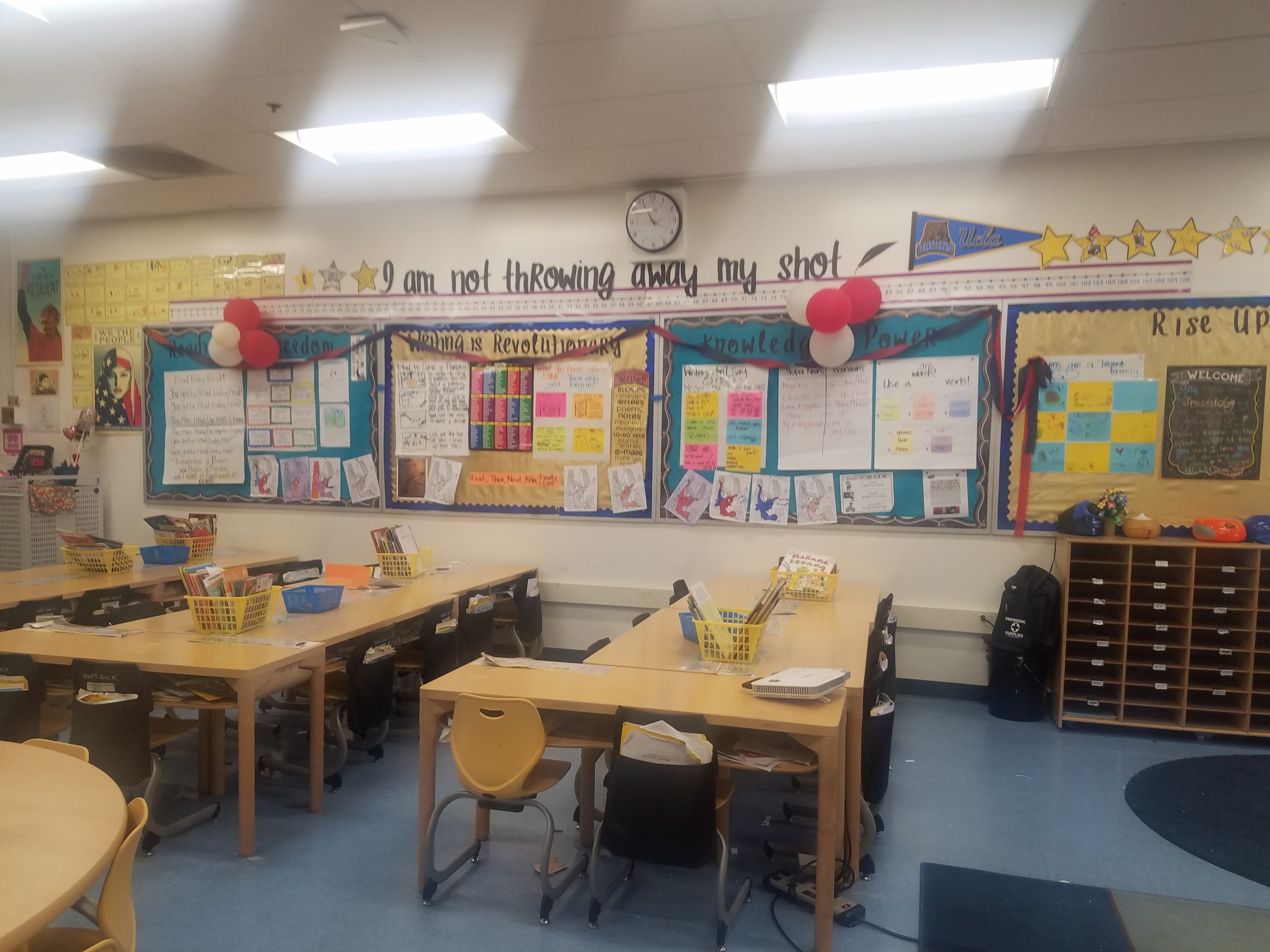

I am now an educator, and use my teaching as a tool of activism. I believe that a better world is possible and that community is what will help us to get there. I wrote my dissertation on liberatory teaching and learning in early grades because I believe that children of all ages are capable of having deep conversations and impacting the world around them.

I get to know my students and families and include their cultures and traditions in our classroom space. I begin each year teaching my kids that love and respect for one another are tantamount to any other learning that we do. I share the Mayan-inspired poem “In Lak ‘Ech,” and we say it each day as our daily affirmation. I spend time talking to my kids about the problems they see in the world and the power they have to make change, not just when they get older, but now. I share about other changemakers who have made the world better, and make sure to include lots of different examples ranging from many different experiences and identities. I have created content for Little Justice Leaders and presented at conferences all about how we as adults can create space for children to be their most authentic selves and to grow into the inspired leaders that our future needs and deserves. I founded Love & Liberation Educational Consulting, LLC so that I could support other educators and schools by helping them to better understand themselves and how their own histories impact their work in the classroom. I use my voice to advocate for the National Iranian American Council, Arthritis Foundation, and Radical Monarchs, amongst other organizations I have volunteered with over the years.

Coming together with those who are similar and different from us, loving each other as we do ourselves, and caring for each other with all of the fiber of our spirits is the only way that we can rise to the glory of what this nation has always been intended for. I dream of a world of the future where our children can be free and fearless, and I work day in and day out for it.

I hope you will join me.

Shadi Seyedyousef is an educator, scholar, and activist who lives in Los Angeles, CA. She is also founder and CEO of Love & Liberation Educational Consulting, LLC that is focused on doing the work of creating a better world for all through radical hope, revolutionary love, joyful resistance, and critical praxis.

“The Long Tunnel” is a series of articles reflecting on the impact of Sept. 11 and how it has shaped the world we live in today. You can read more in the series here.