It has been over six months since the city of Kabul fell under Taliban control during the group’s whirlwind military campaign across Afghanistan. The withdrawal of US troops may have ended a 20-year war, but an aftermath of pervasive violence, human suffering, and political and social tension remains.

Following the Taliban’s seizure of power, financial aid provided by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was abruptly halted and governments froze the Da Afghanistan Bank’s (the country’s central bank) funds held in overseas reserves. International financial aid had amounted to about 75% of the government’s budget and funded many essential services, like healthcare and education. The abrupt loss of funds paired with the absence of a financial structure under the Taliban launched the country toward an economic collapse and a humanitarian crisis.

Electricity is fundamental to a successful economy as well as human security, and the current power outages in Afghanistan indicate a system that is already suffering.

The international community has since started providing humanitarian aid, but their attention has largely shifted to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which began at the end of February 2022. Last fall, the EU pledged $1.15 billion to humanitarian aid, and in January 2022 the US announced it would contribute $308 million. President Joe Biden signed an executive order to split the $7 billion of frozen Afghan funds currently held in the US, designating half for additional humanitarian aid and the other half for relatives of the victims of 9/11.

For those living in Afghanistan, the help cannot come fast enough. Over a million residents fled Afghanistan during the Taliban’s takeover and the following economic crisis. Jobs and incomes are disappearing (with a disproportionate impact on women, who experienced a 16% drop in employment levels in the fall of 2021); hospitals don’t have the resources for staff wages or medical supplies; and millions of people are facing food insecurity. According to the UN, 97% of Afghans could fall below the poverty line by the summer of 2022 if the nation’s political and economic crises are not addressed — and now, this looks almost certain to occur.

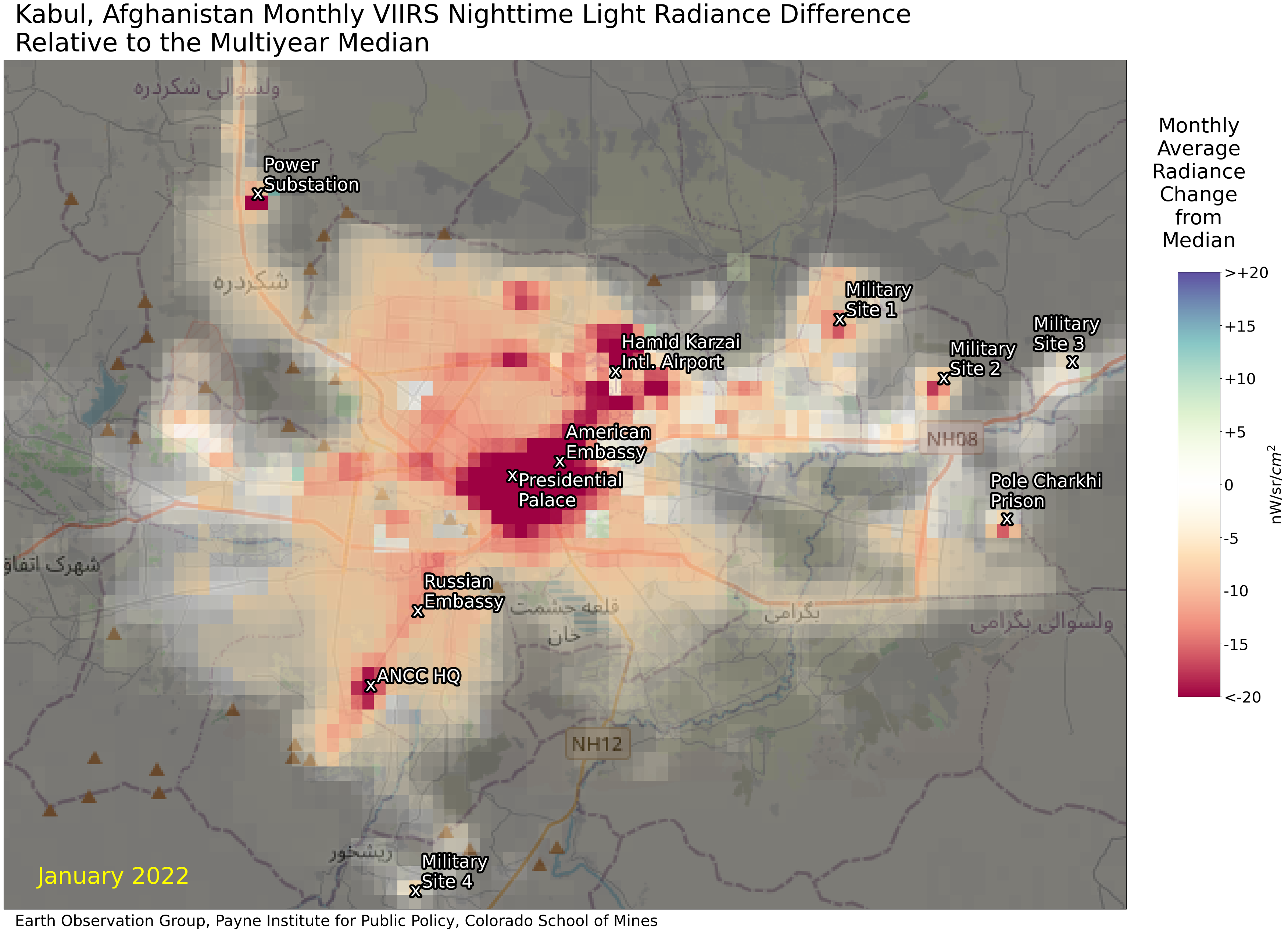

Unplanned power outages hitting Afghanistan have further aggravated the situation. About 80% of Afghanistan’s electricity is imported from neighboring countries in Central Asia. Despite previous reports that the Taliban has been unable to pay Afghanistan’s energy bills, it did sign an agreement with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to continue importing electricity in 2022. But electricity reliability remains a concern, and in January 2022, Uzbekistan unexpectedly cut 60% of Afghanistan’s imported electricity due to technical problems that lasted multiple days.

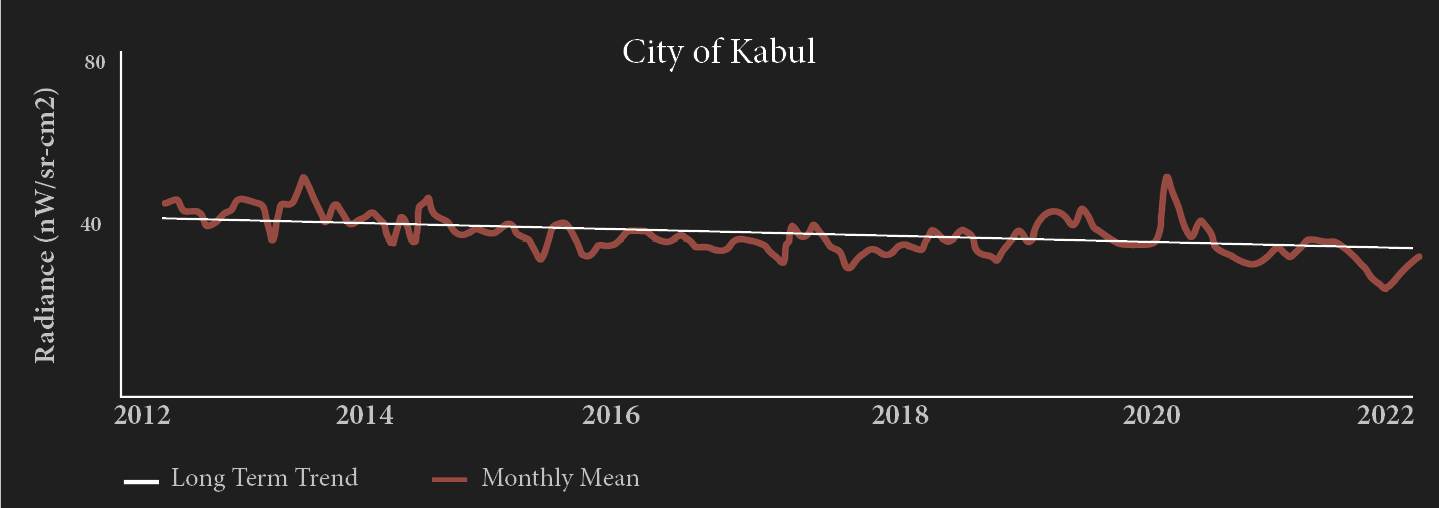

Measurements provided by the Payne Institute’s Earth Observation Group (EOG)‘s VIIRS Nighttime Light create a unique view of the situation in Afghanistan. While the images are from space, the patterns can provide insight about what may be happening on the ground. Payne Institute uses data provided by the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS), an instrument on a satellite co-operated by National Aeronautics and Space Administration and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that collects near-real-time imagery of the Earth, to monitor and report monthly light radiance measurements at sites across the world. They have been observing the radiance at multiple locations in Afghanistan for nearly a decade.

Changing light patterns are not new for Afghanistan, which has dealt with rolling power outages for decades due to issues with supply and conflict, but the departure of US troops, the Taliban’s dominance, and the country’s plunge into an economic crisis create new concerns about electricity blackouts. Electricity is fundamental to a successful economy as well as human security, and the current power outages in Afghanistan indicate a system that is already suffering.

A SATELLITE VIEW OF CITY LIGHTS

To better the situation in Afghanistan, the EOG looked at the lighting patterns of three locations in Afghanistan: Kabul, Kandahar, and Bagram.

Kabul

Kabul is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Looking at long-term trends, the lights in Kabul’s city center and the Hamid Karzai International Airport have both decreased over the past decade, but while the decrease in the city center has been gradual, the airport lights experienced two historic drops: one in March 2016 and another in March 2017. Afterward, the radiance remained at a lower level.

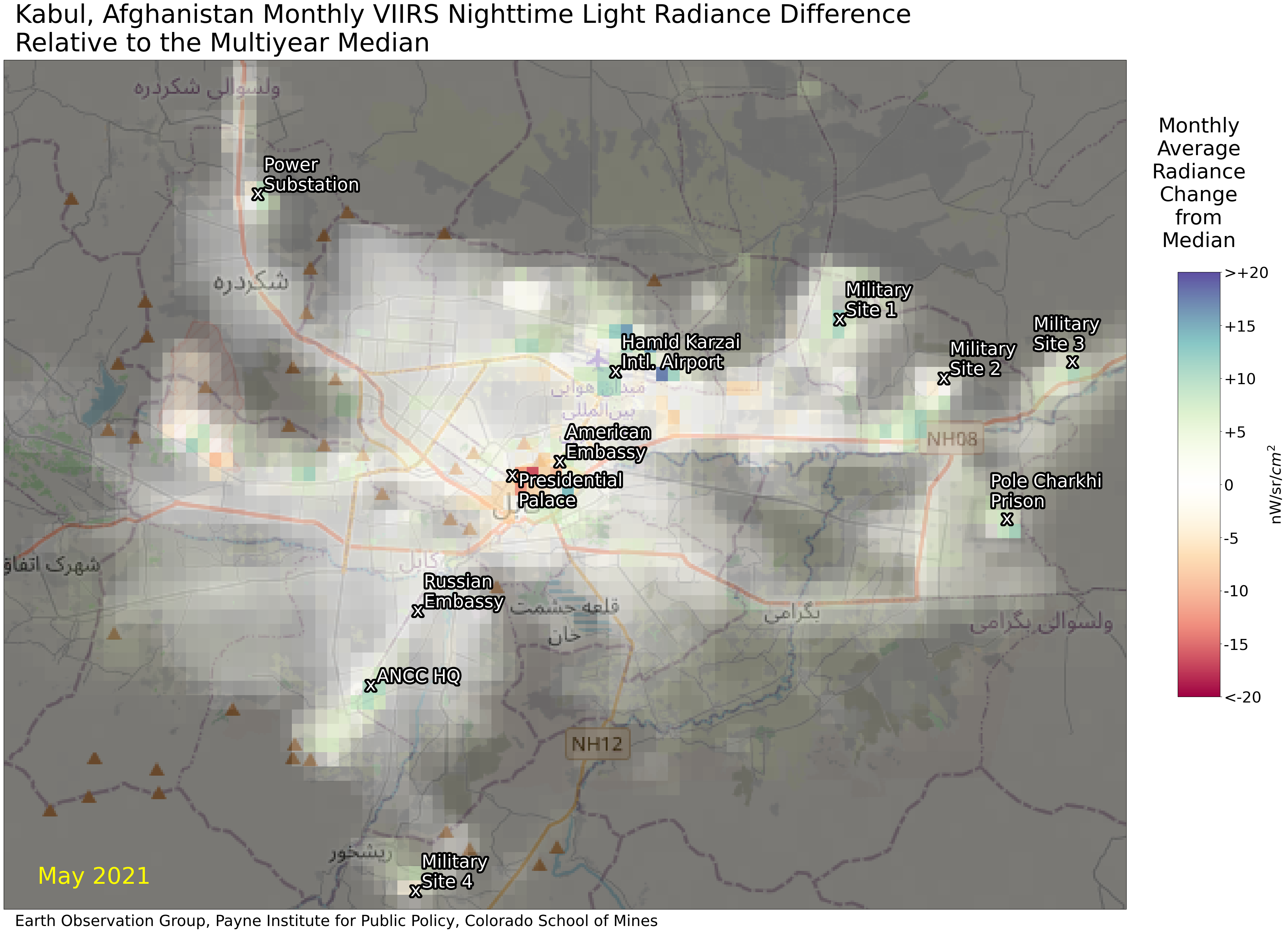

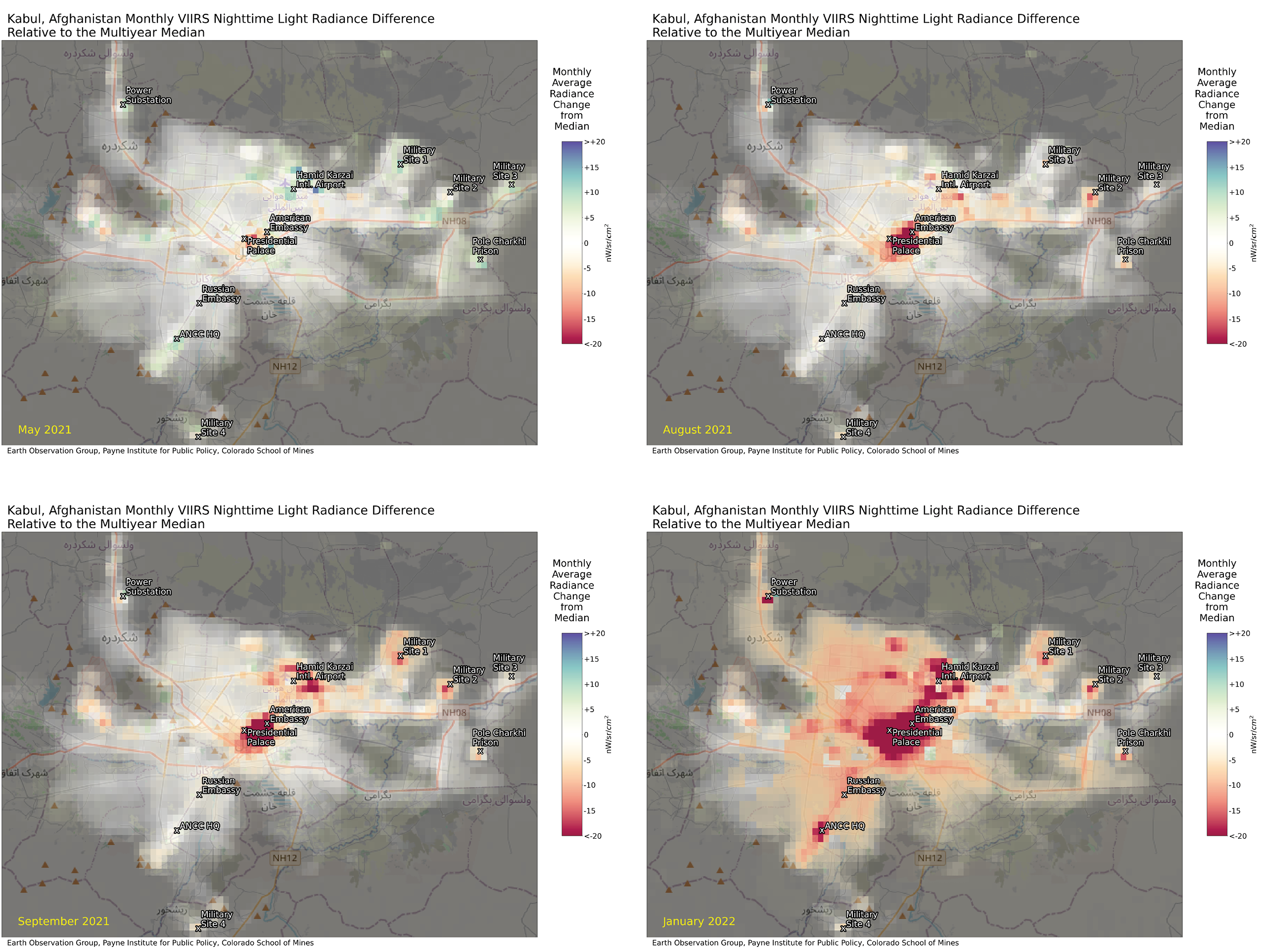

Just after May 2021, the radiance measurements in Kabul dropped sharply, especially in the city center where the Presidential Palace and US Embassy are located (Fig. 1).

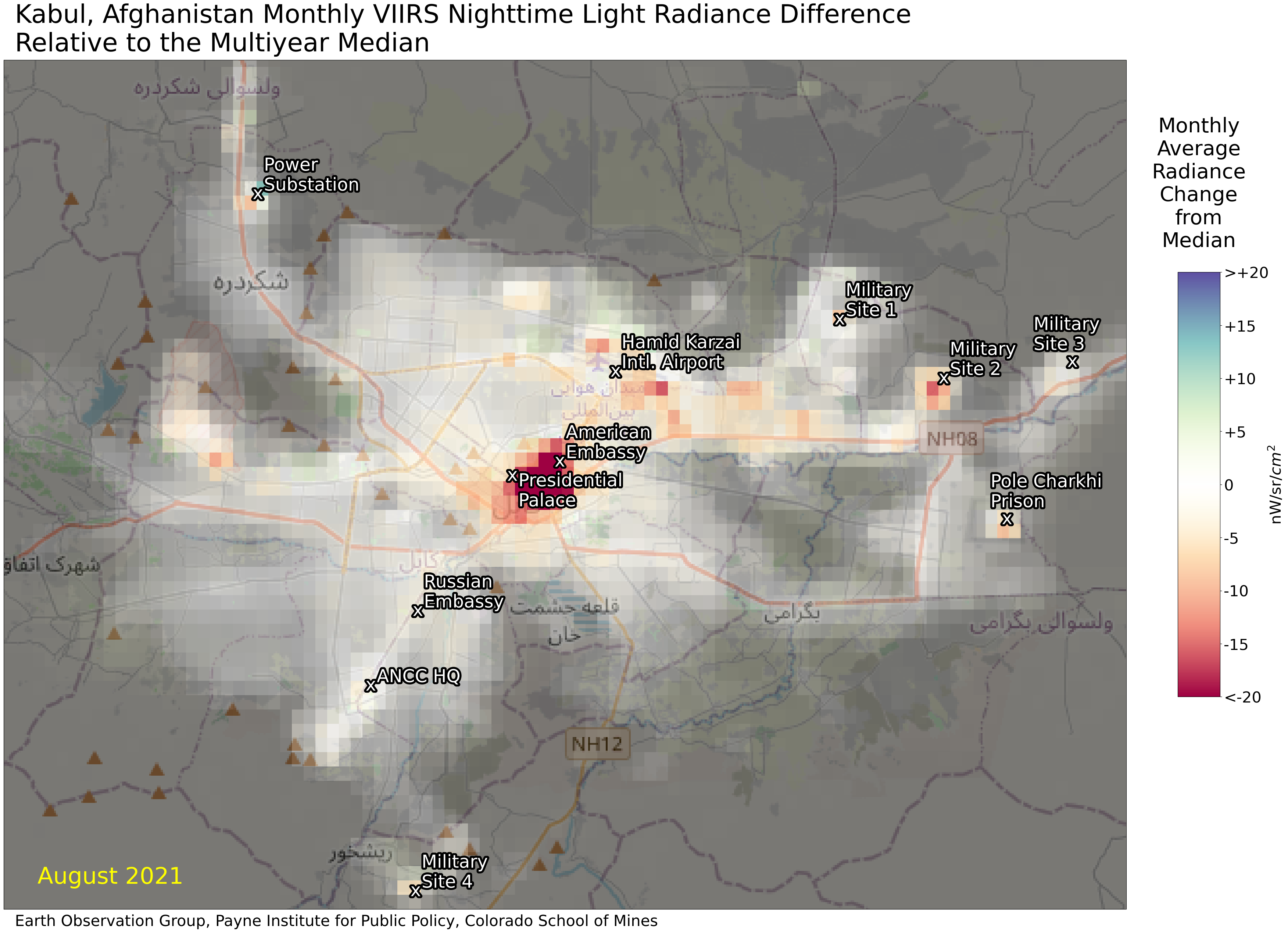

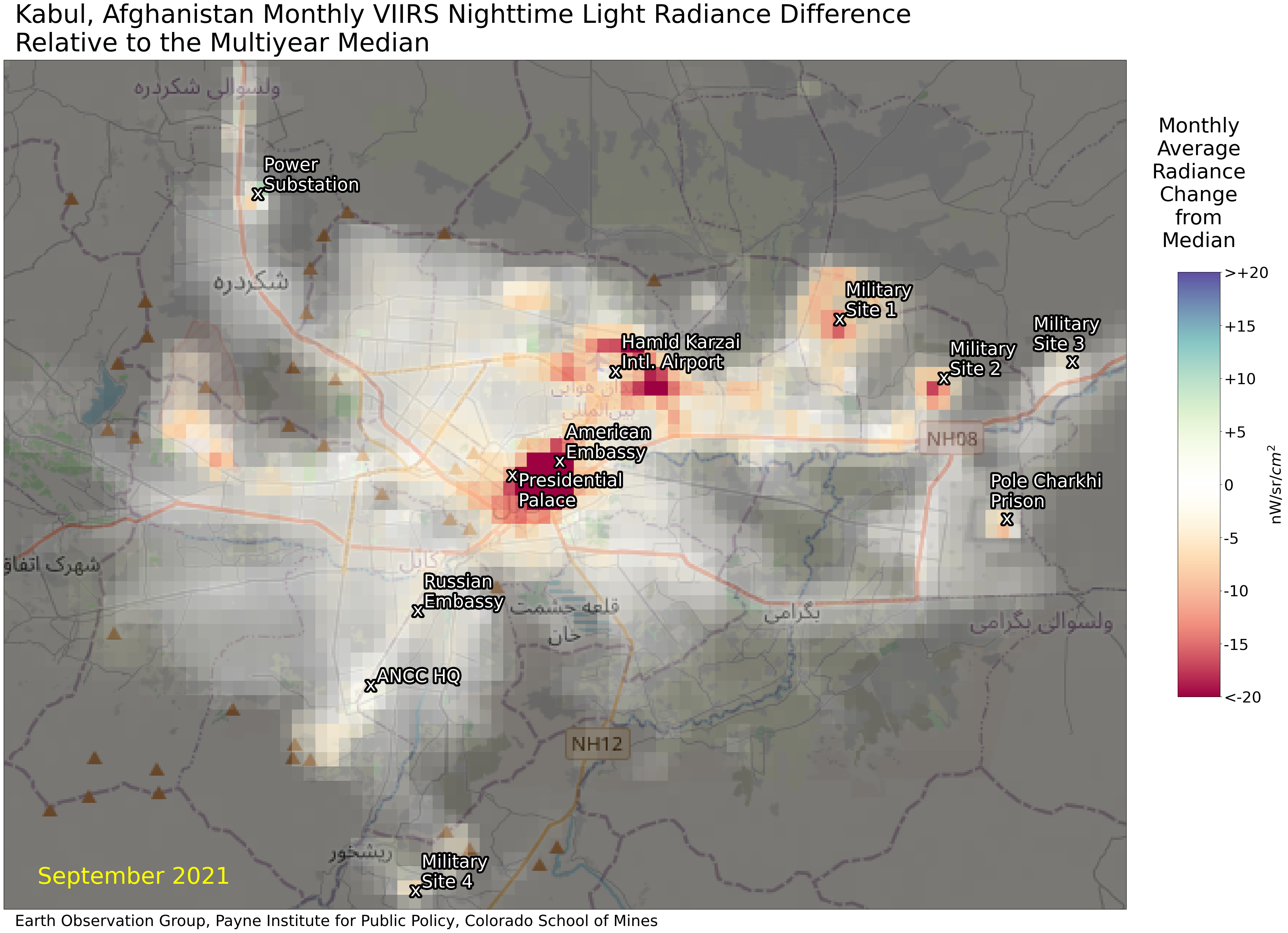

During August 2021, light levels at the Hamid Karzai International Airport remained close to normal as the US and NATO maintained control of the airport and helped evacuate over 100,000 people from the country. But by September 2021, the lights went dim as the last US troops were withdrawn and the Taliban took control of the airport (Fig. 2). International airlines rerouted their commercial flights away from Afghanistan, and despite the Taliban’s request for international flights to resume, the commercial activity remained limited.

There are multiple military sites located in Kabul, including a CIA “black site” prison known as Salt Pit (labeled as Military Site 1 in Fig. 3). Unlike other radiance trends in Kabul, the site shows a significant increase in activity after June 2016. The compound was also used by US forces during the Taliban take-over. In April and May 2021, after the announcement that US forces would leave the country by September, personnel began destroying some of the compound buildings to prevent sensitive materials from falling into Taliban hands. After the Taliban entered the city, the compound was used to help evacuate hundreds of people. They were flown to the nearby Hamid Karzai International Airport via helicopter to avoid Taliban checkpoints.

Near the end of August, US forces demolished more equipment and structures of the compound before completing their evacuation and leaving the site to fall under Taliban control. The lights, which dimmed during the summer of 2021, dropped to darkness by September. The compound was still empty in October 2021, but a Taliban commander said the group planned to use the site for military training in the future.

The light levels across the city remained similar to September 2021’s condition for a few months, but in January 2022 there was another significant decrease in radiance that extended across a larger area. Kabul was among the locations that experienced unexpected power outages in January 2022, which may have contributed to this decrease. These figures below show the change in the month’s average radiance level compared to the median in Kabul before, during and after the Taliban’s seizure of the city (from May to September 2021). The fourth picture is from January 2022. Red indicates that the light levels are lower than usual and blue indicates that they are higher.