When a group of Cameroonian separatists targeted local civilians with a campaign of murder, rape, dismemberment, and arson, peace activist Feka Parchibell attempted to raise awareness.

A Maryland-based man aligned with the separatist movement told her that were she to continue with her activism, a grim fate awaited.

“He told me that they had just murdered a lady, and the video was on social media, where they showed how they were cutting off her head. And he told me I was going to face something similar,” Feka said during a December 2021 phone call.

The US-based man who threatened her was a member of the Cameroonian diaspora community who allegedly supported separatists in his home country through remittance payments. Each year, billions of dollars in remittance payments flow out of the United States and into countries around the globe. These payments often provide medical, nutritional, educational, and other critical humanitarian lifelines, spurring hope and creating opportunities for struggling communities overseas. But sometimes, they can be used to support armed struggles — and even to fund war crimes.

Undeterred and driven by her belief that the United States draws a hard line on human rights violations, Feka demonstrated in front of the US Embassy in Yaounde on Aug. 17, 2020. “We all know how the US government is strict on human rights. So I could not understand why those people could be in the US, and they are instigating these guys back home to destroy,” she said. She and others were arrested for this protest in August 2020 but ultimately released.

Less than two weeks after our call in December 2021, she was killed in a car accident.

This last telephone conversation, and a seemingly simple set of questions that emerged from it, led to this article. Do we already have, or do we need, a more comprehensive federal policy to govern remittance payments from US-based individuals to fund conflicts abroad? Or are there other ways to prevent US-based individuals from funding crimes internationally? The answer is not so simple.

REMITTANCES ARE LIFELINES

Per World Bank data, over $650 billion of recorded personal remittances were received worldwide in 2020, nearly $70 billion of which originated in the United States. And according to the International Monetary Fund, “Unrecorded flows through informal channels are believed to be at least 50% larger than recorded flows.”

Are there other ways to prevent US-based individuals from funding crimes internationally? The answer is not so simple.

Scott Paul, Humanitarian Policy Lead at Oxfam America, spoke to us about the positive impacts of remittance payments to Somalia, stating: “Remittances account for about a third of the country’s entire GDP. About 90% of remittances are spent by people to meet immediate needs of food, shelter, education, and basic healthcare. The remainder is invested in small businesses that communities depend on. So this is a really critical financial flow.”

When it comes to conflict specifically, researchers acknowledge remittances can serve both to mitigate or sustain conflict abroad. For example, Fabio Mariani et al. noted in the 2017 study “Diasporas and Conflict” that diasporas are willing to contribute to war efforts of their group of origin:

“In case of actual conflict, this fuels the intensity of war, pushing the origin group to allocate a higher share of its members to fighting. However, the impact of the diaspora is not always peace-wrecking, as the strengthened bargaining power that it confers to its group of origin may deter the rival group from fighting and make the peace process more likely.”

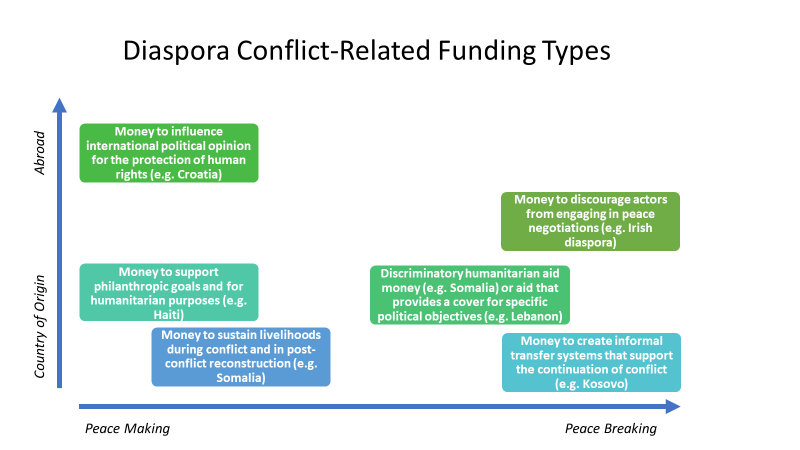

In 2019, Mari Toivanen and Bahar Baser outlined ways diaspora groups can influence peace-making or breaking. The following chart is based on their findings showing the various ways remittances impact conflict and peace processes in countries. Diaspora can have peace-making impacts both in their country of origin and abroad by influencing political opinion, supporting philanthropic goals, and sustaining livelihoods. For example, the Haitian diaspora in Miami actively supports several humanitarian aid organizations that offer short and long-term assistance. Conversely, diaspora communities can also engage in peace-breaking activities by discouraging peace negotiations, providing discriminatory aid money, and even bankrolling the continuation of conflict, as is happening in Cameroon.

Despite the capacity of remittance payments to sustain conflict, they are generally viewed as a net positive, except — and this is a big exception — when used to fund terrorism. Research by James A. Piazza suggests that diaspora funding significantly increases the survivability of terrorist organizations. As an example, Piazza cited the Kosovo Liberation Army, active in the Balkans in the 1990s and 2000s, noting it was formed and supported by Ethnic Kosovar Albanians living in Europe, allowing the movement to continue despite a lack of popular support by Kosovars in the former Yugoslavia.

DO REMITTANCES FUND TERRORISM ABROAD?

To better understand current US government oversight of international remittances, we spoke to Jason Blazakis, former State Department Director of the Counterterrorism Finance and Designations, now Professor of Nonproliferation and Terrorism Studies at the Middlebury Institute. Blazakis described a triangular relationship between the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, law enforcement, and the financial industry (both banking and non-banking entities). The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network relies on the financial sector to submit Suspicious Activity Reports or Suspicious Transaction Reports in order to carry out its mission of safeguarding the US financial system, the difference being the object of suspicion. Suspicious Activity Reports focus on customer actions like multiple failed login attempts, failure to provide required identification, etc. In comparison, Suspicious Transaction Reports focus on deposits, transfers, and withdrawals.

The number of Suspicious Activity Reports generated is staggering. For example, in the first seven months of 2022 alone, the financial industry submitted over 5.3 million Suspicious Activity Reports, 911 of which were directly related to terrorism. “There could be an important needle that’s being missed just because of the volume of what’s coming in from financial institutions,” said Blazakis. Not to mention, as Blazakis pointed out, Suspicious Activity Reports are only as good as the internal algorithms or compliance guidelines established within each financial entity. In relation to terrorism finance, Suspicious Activity Reports only focus on individuals and entities designated or sanctioned by the State and Treasury Departments under Executive Order 13224.

“Generally, every financial institution is different in how they arrange their compliance sections. Some spend money on it and bring in experts to help run these entities. But then you have the very real world challenge of newer kinds of entities, like cryptocurrency entities, that really are just beginning their work in the area of customer due diligence,” said Blazakis.

Paul, from Oxfam America, said he was not surprised by the number of Suspicious Transaction Reports: “[financial institutions] have little incentive to provide regulators with the most useful information. They have every incentive to provide the regulators with as much information as possible so as to diminish the possibility of regulatory enforcement.”

US federal law prohibits the funding of terrorism, but limitations related to the mental component of the crime — i.e., what the funder has to know to be held culpable — complicate the ability of authorities to prosecute in many cases.

Given the nature of crime and criminal networks, the likelihood that individual diaspora members are tuned into the nuanced plans of an organization they donate to is minimal.

Under the relevant section of the US Code prohibiting the financing of terrorism, individuals can face prison terms of up to 20 years for providing or gathering funds to carry out any act intended to cause death or serious bodily harm to a civilian or other non-combatant. But various qualifiers render this section toothless with respect to many members of diaspora populations. First, to be held responsible, the individual must have provided these funds intending to fund the deadly or harmful act. Second, the act, by its nature, must be aimed at intimidating a population or compelling a government or international organization to undertake or refrain from undertaking a specific action. In short, the funder must have insider information on the plans of an organization they seek to fund, and US authorities must be able to determine the specific aims of the act.

Given the nature of crime and criminal networks, the likelihood that individual diaspora members are tuned into the nuanced plans of an organization they donate to is minimal. And in many cases, foreign governments have little to gain from turning over evidence and intelligence to the US government for activities related to separatists and other dissident groups, making it challenging to ensure American authorities can determine the aims of a specific act with the requisite certainty.

When it comes to combating the transfer of illicit funds overseas, sanctions are a key element of the US policy arsenal. As described by the Atlantic Council in a 2020 report, “Economic sanctions have become a default setting for the US government and Congress to respond to policy problems that seem to require more than a demarche and less than military action.”

The US Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control has broad authority to administer and enforce economic sanctions against countries and individuals engaged in various criminal activities, ranging from terrorism to narcotics trafficking. In particular, the Office of Foreign Assets Control can prohibit transactions associated with specific actors and sectors, thereby banning trade and financial transactions that would otherwise prop them up. In addition, hefty fines disincentivize traceable violations of sanctions and prohibited transactions.

The Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctions can target individuals or programs, with the latter generally applying to entire countries, specific sectors within a country, or entities and groups seen to be at odds with US policy goals, ranging from blood diamonds to election meddling. But these sanctions still need to be improved, failing to consistently target the bad actors in all regions and enabling relatively savvy bad actors to continue collecting foreign contributions undeterred. And the rise of cryptocurrency has further complicated matters.

USING CRYPTOCURRENCY AS A REGULATORY TOOL

By its very nature, cryptocurrency exists beyond the structures of existing government controls, making them the perfect fit for criminal transactions. Though the United States was quick to impose a broad range of sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia and Russian-aligned causes have raised upwards of $2 million in crypto funds since the war started, according to a report by Chainalysis, a blockchain data platform. According to the report, these funds have been distributed across some 54 organizations, which notes that sanctioned individuals and entities have openly seized on crypto as a means of raising funds since the start of the war.

And while increasing global authorities endeavor to regulate crypto, governments in conflict-prone and fragile states are less likely to prioritize the development of crypt-related policies, according to financial crime risk consultancy Fintrail. As a result, crypto transactions in the states most prone to conflict and internal turmoil are far less likely to occur on international, centralized exchanges that are accountable to Know-Your-Client policies and other financial sector safeguards. These exchanges can occur in cash and be facilitated via social media, making them nearly impossible to track and trace.

Crypto regulation is a key priority for US authorities. In March 2022, President Joe Biden issued an executive order to ensure the responsible development of digital assets. That same month, Attorney General Merrick Garland announced the launch of an interagency law enforcement task force focused on enforcing Russia sanctions. But as matters currently stand, US policies related to illicit remittance payments are riddled with gaps.

As US law enforcement agencies scramble to counter crypto-related threats, their efforts may create a loophole to address the intent obstacle in terrorism-funding cases described above. According to law firm White & Case, the intent is not explicitly mentioned in the Department of Justice materials surrounding these efforts; thus, it is possible exchanges could be held responsible for what other people do using their platforms.

COMBATTING THE FUNDING FOR CRIMINAL ACTIVITIES

Where does this leave us in terms of our original, “simple” question about comprehensive federal policies to combat the funding of criminal activity by US-based individuals? Kay Guinane, former Director of the Charity & Security Network, warned there is “a danger in trying to regulate your way out of the problem, the unintended consequences may be counterproductive to your ultimate goals.”

Echoing Guinane, Paul said he challenged the framing of our question as the right framing. “I would propose to US policymakers that their job is to minimize the overall level of financing for prescribed actors and increase the transparency of it as much as possible, while not interrupting other important financial flows. I don’t think there is much to be gained by trying to push illicit flows out of the formal system…in ways that can’t be seen versus ways that can be seen and tracked and pursued [by law enforcement] through formal financial institutions.”

Since 2015, Oxfam and its partners have been, according to Paul, “urg[ing] a recalibration of the risk-based approach to banking regulation” and, in jurisdictions where there’s no private sector appetite to engage, for “the US government to share the risk of banking in high-risk areas.” Paul explained that the US government could do this in a variety of ways, for example “…by laying out a more specific set of requirements that banks can meet, transitioning from a risk-based regime to a rule-based regime [or by having] the US government itself facilitate funds transfers through a US mission or using the Fedwire capacity and the New York Federal Reserve.” This would enable funds to continue to flow through transparent, regulated channels, even where market incentives on their own are insufficient to encourage banks to provide services.

The solution for Cameroon, it appears, is not to limit important remittances that individuals rely upon, but to redouble intelligence efforts to identify, both domestically and internationally, criminal elements. and apply appropriate criminal or financial regulatory actions on their activities — whilst pursuing diplomatic cooperation with the Cameroonian government to do the same.

Ultimately, the United States is walking a fine line between protecting such values as free speech and the free flow of aid money and other capital and preventing human rights atrocities. The solution to this conundrum will ultimately lie in tradeoffs — the maintenance of fundamental rights protections on the one hand and on the other, the identification and enactment of policies that will effectively deal with human rights abusers and those who wronged Feka.

Ingrid Burke Friedman is a former US diplomat, fellow at the Harvard Davis Center for Russian & Eurasian Studies, and Features Editor at JURIST.

Amy Madsen is a former US diplomat, Executive Director of Undivided: Women, War & The Battle for Peace, and author of “Green Zone Diary: A Diplomat’s War Story.”