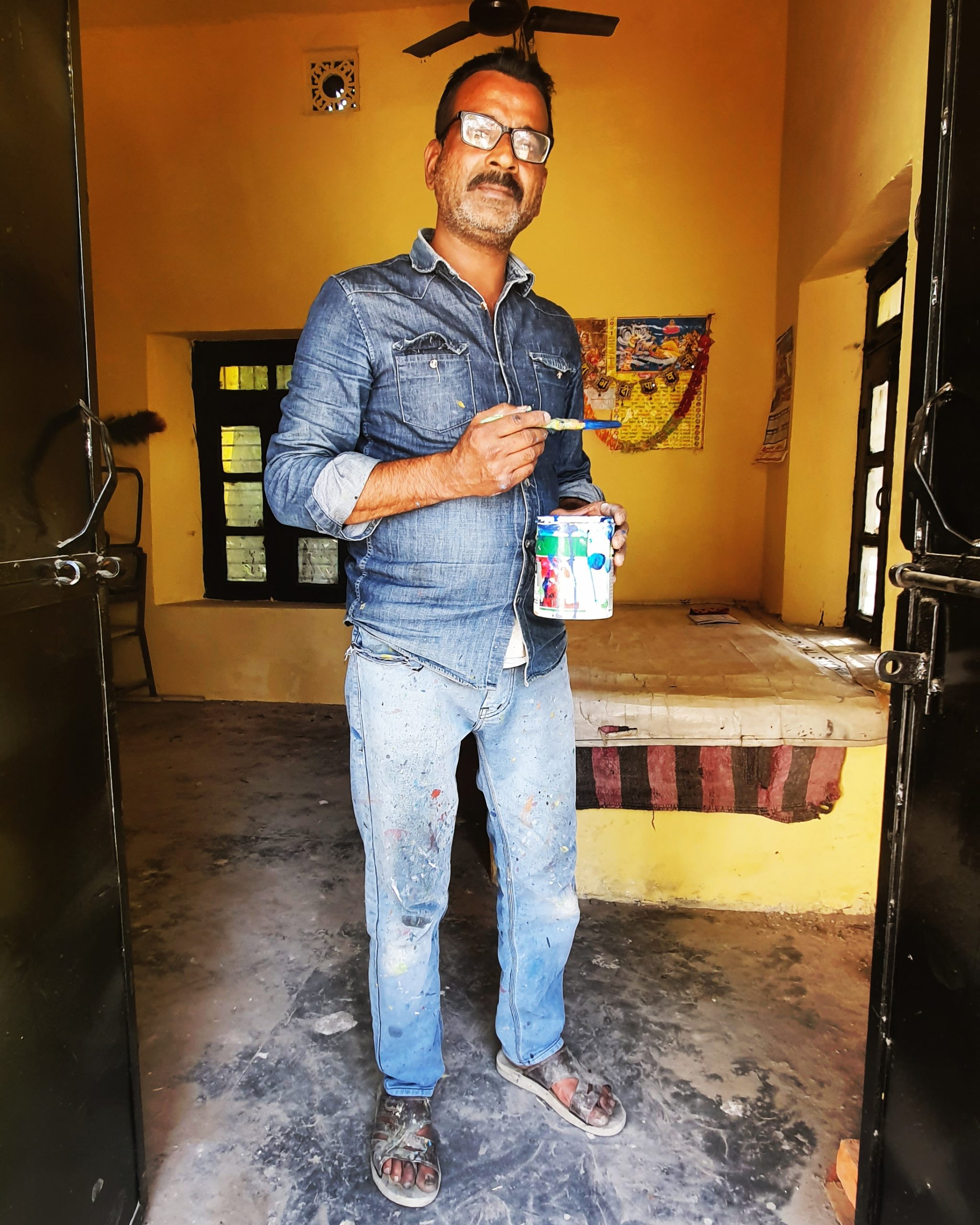

Unlike most other local artists who paint directly, Subhash first sketches his art with chalk. It takes more time but he says that it affords his art a certain finesse. Although Subhash has “uncountable” paintings under the schemes to his credit, he admits that painting was never something he wanted to do for a living. “I always wanted an office job, but the dire financial conditions at home prevented me from going to university. One of my friends, a street artist, knew I painted as a hobby and offered me a gig. 25 years later, I am still here,” narrates Subhash.

Subhash’s slight hesitation toward this profession comes from the lack of organizational and financial stability within the industry. The artists have been working under contractors that are outsourced through tenders by civic bodies. Under this system, the artists claim to be paid around INR 9 ($0.12 USD) per square foot compared to INR 35 ($0.47 USD) when commissioned directly by the civic body. This middleman system has thus reduced their profit margins. Moreover, the contractors are not artists themselves. Hussain complains that this restricts transparency in operations.

“We’re also not reimbursed for our paints and equipment,” states Parveen. He is quick to add that most painters use eco-friendly paint. “Not only is it good for the environment, but it also does not harm our skin,” adds Parveen, holding up his blue and purple-stained fingers.

Skin contamination is one health hazard associated with painting. But it’s not the only one. Two years ago, Hussain fell down the ladder and broke his leg while painting high up on a wall. He has a rod fitted into his leg. Hussain wishes that all painters received helmets, safety equipment, and medical assistance to do their job safely. However, he hasn’t put his concerns forward.

These painters seem apprehensive in voicing their grievances and demands because of their gratefulness towards the current government. “Our dying profession has received a new life. At the moment, we are just happy to have regular work at least for the next few months,” states Jha.

The local civic bodies organize several functions and contests that showcase the artwork of various painters. “We are acknowledged with certificates,” claims Parveen, but like the other painters, hopes for more recognition in the mainstream public spheres.

Most paintings are credited to the local civic body alongside the scheme, with the painters’ names and contact numbers appearing in mini fonts on the corner. Their names do not appear at all when a painting has been made by more than one person.

“I do not know if the city has truly become clean or smart or not, but people love our artwork. However, some citizens also feel that the art is part of propaganda, and the government needs to divert their spending on more pressing issues.”

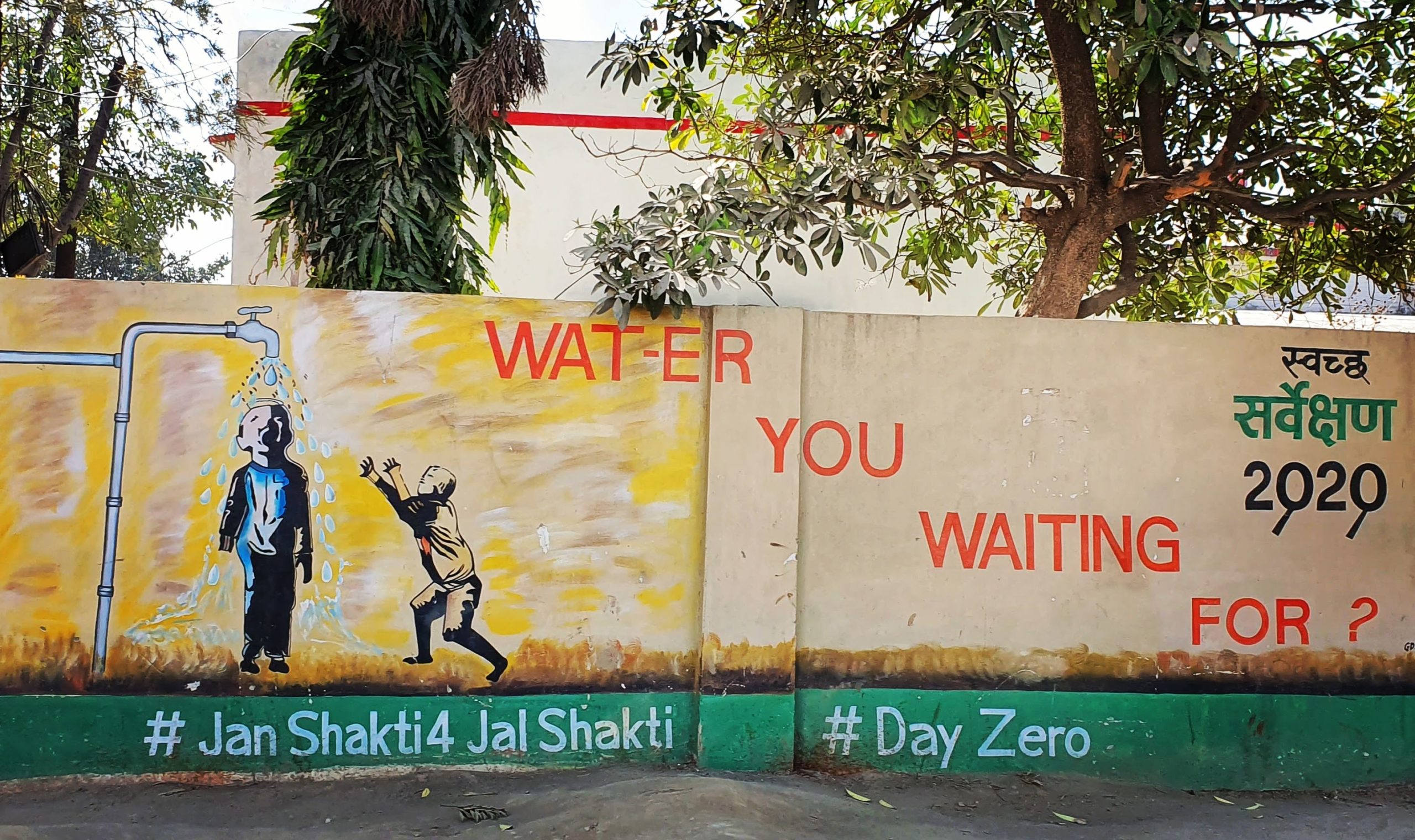

However, the artwork that has brightened the former drab walls of town seems to be getting good feedback from citizens. “I do not know if the city has truly become clean or smart or not, but people love our artwork. However, some citizens also feel that the art is part of propaganda, and the government needs to divert their spending on more pressing issues,” says Jha.

The performative nature and the propaganda value of the paintings will remain an unending debate between various political factions and sections of society. But Saharanpur’s Municipal Commissioner, Gyanendra Singh, believes that this social art goes a long way in inspiring people to be responsible citizens. “The city has become beautiful with big, bold and bright messages which will last in the memory of people. As a result, people will think twice before throwing garbage, defecating and spitting on the walls,” he adds. However, Singh feels that groundwork operations need to be coupled with awareness. This is why budgets are also allocated for conducting skits, school collaborations, and civic discipline drives along with the paintings.

Singh’s sentiments resonate with the aims of various schemes for which these wall paintings are made. For example, apart from making “Keep Your City Clean” imagery, the civic body is also setting up large dumpsters throughout the town.

As a result, cleanliness standards in the town seem to have improved. But it remains to be seen if and when the other social messages will be heard. For example, while paintings of women’s empowerment adorn several walls in town, hardly any women can be seen painting these walls. The awareness around planting trees is abundant; however, new highways and road work calls for the felling of several trees in the districts.

The need of the hour is thus: This art must stop existing in a vacuum and intersect with grassroots work. Paying for paintings on walls is one start — but it is far from enough. Various government departments also need to work together and participate in the call for action they put out in the paintings.

The painters feel that their social art is one step forward towards achieving that. The initiative is also a way for the government and the arts to collaborate together for the sake of the collective good. And the government could use more art — after all, art has the power to transcend geographical and linguistic barriers to shift thinking. This enormous potential of street art is what the painters want their children to appreciate. Hussain hopes his daughter, a 12-year-old aspiring artist, will grow up in a truly smart city and, like him, make it more accountable through her art.