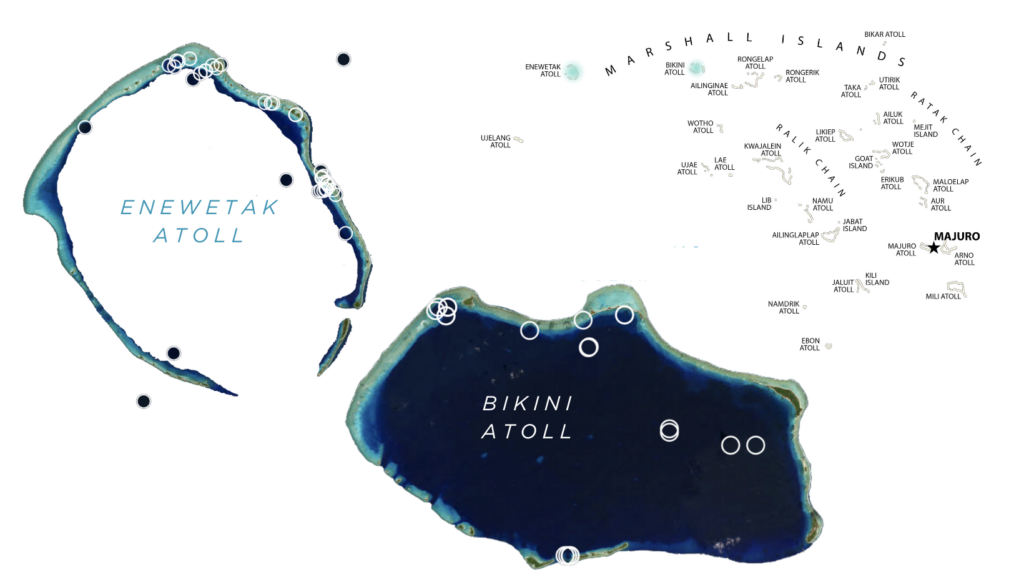

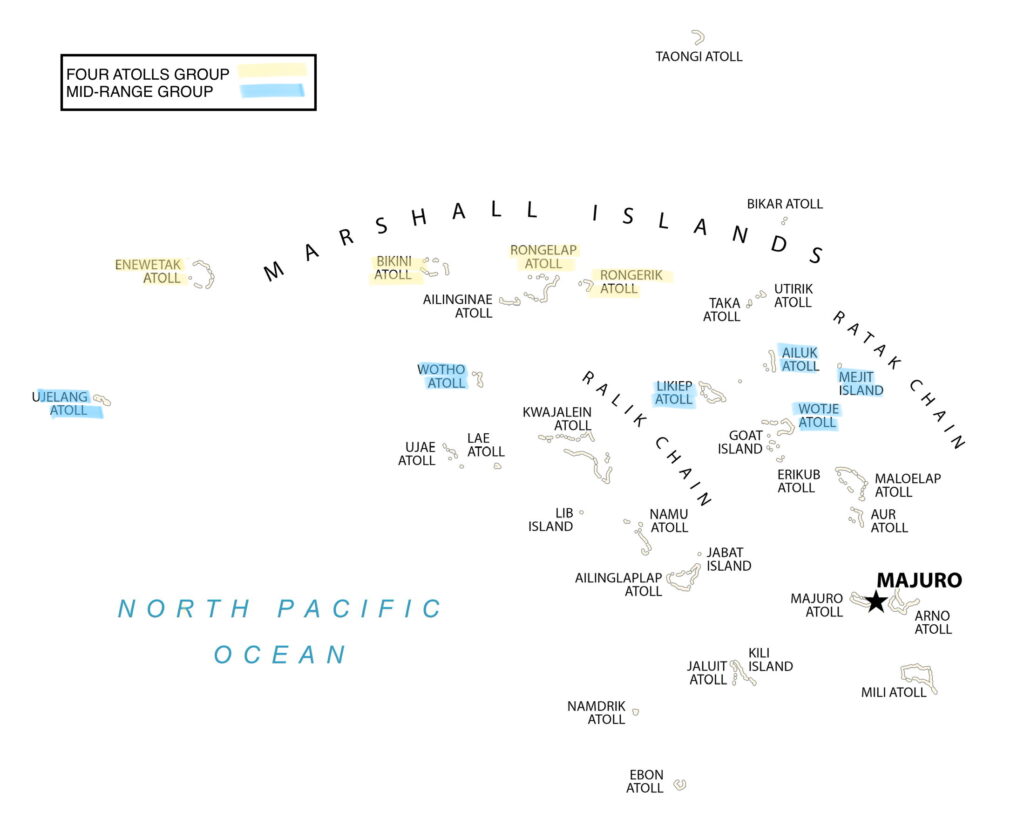

Tucked away in the azure waters of the Northern Pacific halfway between Hawai’i and New Zealand, the remote chain of tropical islands, islets, and ring-shaped coral atolls seemed the ideal proving grounds for the United States’ Cold War-era nuclear testing program. Between 1946 and 1958, a total of 67 nukes were exploded in the Marshall Islands — the equivalent of dropping 1.6 Hiroshima bombs every day for a dozen years.

The twelve-year bombing campaign vaporized entire islands and dotted lagoons with radioactive bomb craters, forever displacing generations of Marshallese from their paradisiacal home turned nuclear wasteland.

Islanders received direct exposure to poisonous fallout, starved in exile on too-small islands with inadequate food supplies, and were later temporarily moved back to their irradiated homes to be unknowingly used as test subjects in human radiation experiments. Now, the resulting cancers and mysterious birth defects have been passed on to the children of nuclear victims.

After decades of cover-up and secretly withheld information about radiation exposure, the United States still has not recognized the extent of the nuclear program’s impacts or paid out full compensation to its victims.

This year provided the Marshallese an opportunity to finally seek justice in the form of an apology and total financial reparation. Certain economic provisions of the Compact of Free Association — the key international treaty that determines the compensatory relationship between the Marshall Islands and the US — expired at the end of September. Its renegotiation gave room to rewrite the details of that relationship.

Both parties signed to renew the Compact and two other related agreements on Oct. 16, all of which are now slated for congressional approval. But according to Marshallese officials I spoke to, the new deal doesn’t satisfy the conditions of justice. They say that the new deal does not compensate the victims adequately, and it does not issue a formal recognition of and apology for the nuclear legacy. What began as a chance to address the Compact’s past failings has become nothing more than a reinforcement of them, and the Marshall Islands’ nuclear issue has fallen between the cracks yet again.

“You Will Always Be Family To Us“

By the 1980s, exposed and uncompensated islanders had started taking matters into their own hands, hiring attorneys to sue the United States for its crimes. With some $7.1 billion in damage claims making their way through US courts, America offered the Marshallese a settlement deal.

In 1986, then President Ronald Reagan encouraged the people of the Marshall Islands to ratify the original Compact of Free Association, promising them that “you will always be family to us.” Trusting his words and still not totally informed of the full extent of what happened to them (thousands of government documents about their exposure were still classified at this point), the Marshallese signed, locking themselves into an ambiguously worded agreement full of legal loopholes that the US has repeatedly jumped through in the four decades since.

The original Compact did three important things. First, it released the US from any pending legal claims, dismissing the $7.1 billion in lawsuits. Second, it established the Republic of the Marshall Islands as a sovereign nation in exchange for total US military control over Marshallese land and seas, headquartered at Kwajalein military base. Third, it granted $150 million in compensation and established the Nuclear Claims Tribunal as a “means to address past, present and future consequences of the Nuclear Testing Program.”

The international tribunal, created in partnership by both countries, was meant to conduct an objective assessment of the full extent of all nuclear-related damages in order to compensate victims, but it was severely underfunded.

Even though the tribunal evaluated personal injuries and loss of land damages totaling over $2.3 billion, the United States never appropriated more than the original $150 million payment.

Today, the United States maintains that the 1986 agreement was binding in providing the full and final settlement for all nuclear-related claims, and it has declined to give more money to the managing nuclear tribunal since. The US State Department’s official stance is that it has provided more than $600 million to the affected communities — one billion in today’s dollars — which includes the original Compact payment in addition to the resettlement trust funds of the affected atolls and radiation-related healthcare program costs. Even so, these funds account for only a fourth of what the tribunal determined as the rightful reward.

“The US has been so guided by what we signed in 1986,” Ariana Tibon, Commissioner and Justice Envoy for the Marshall Islands’ National Nuclear Commission, said about the original Compact. “It’s hard to sway them we signed that without any knowledge that all of this would happen,” she said, referring to the unexpected health problems and classified information on the testing that would surface in the decades to come.

The terms of the Compact are renegotiated every two decades. The Marshallese hoped to use the 2023 renewal cycle to rewrite the Compact’s compensatory provisions to finally secure the billions still owed to the tribunal, but the State Department wouldn’t let US negotiators officially designate funds as nuclear legacy compensation.

“Our legal responsibility for nuclear liability has been met. It was settled in the 1980s,” Joseph Yun, the US Special Envoy to lead Compact negotiations, told a congressional hearing committee in July.

But Marshallese advocates say the US can’t simply wipe its hands clean.

“What about your moral obligation to me?” Kenneth Kedi, Speaker of the Nitijela, the Marshallese Parliament, responded to the US position in an interview in July. Kedi’s mother spent years of her life living among radiation on two of the nuclearly-impacted atolls, Rongelap and Bikini, where current-day radiation levels still significantly exceed that of Chernobyl and Fukushima, according to a 2019 study from an independent Columbia University research group. She recently died of cancer, which Kedi attributes to her long-term exposure.

Referencing President Reagan’s promise to care for the Marshallese as America’s own kin, Kedi asked, “am I not your younger brother?”

Yun accepts that the damages and effects of nuclear testing linger in the Marshall Islands in the form of displacement and cultural trauma. “The legal responsibilities have been met, but still, there are continuing problems,” Yun said in an interview. “We still have continuing, what I would call, moral and political responsibilities.”

But considering how the US has historically dealt with the repercussions of its nuclear imperialism, it remains unclear if and how those moral and political responsibilities will be fulfilled.

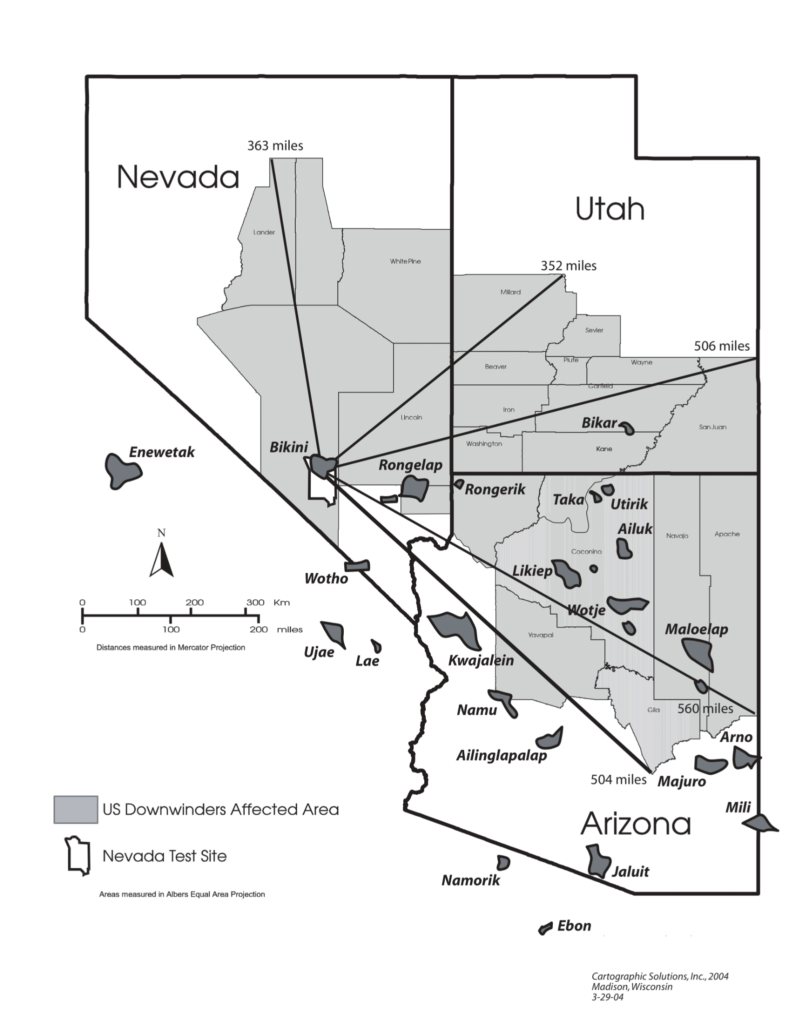

America’s nuclear legacy has been top of mind since this summer’s release of Oppenheimer, the blockbuster biopic of the physicist who spearheaded the building of the atomic bomb. Activism criticizing the film’s omission of nuclear victims’ experiences has resurfaced conversations about the United States’ treatment of Indigenous communities impacted by its nuclear testing, both inside its borders and beyond. Similarly to its treatment of the Marshallese, the US did not pay amends to even its own exposed citizens for decades.

Without any high-grossing film to draw legislative attention toward the Pacific, America’s decades-old promise to the Marshallese remains unfulfilled.

In response, President Biden has promised to finally compensate Native American downwinders of the world’s first atomic bomb test in New Mexico, codenamed Trinity. Meanwhile, without any high-grossing film to draw legislative attention toward the Pacific, America’s decades-old promise to the Marshallese remains unfulfilled.

Many considered Compact negotiations to be the last chance to secure compensation and recognition that America’s nuclear legacy continues to impact the Marshall Islands.

“We can’t wait another 20 years,” said Marshallese Ambassador to the United Nations Doreen deBrum. “There are too many people passing away, too many issues.”