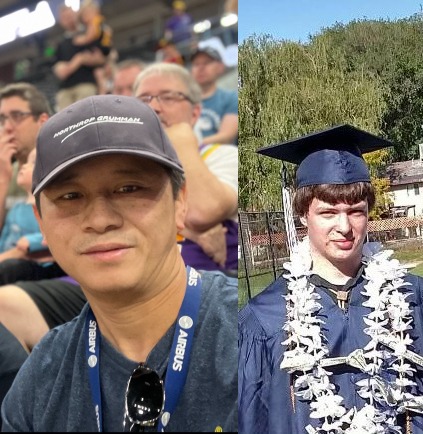

Julie Steinke didn’t see her son, Jonathan, 24, the morning he left their home to go die on the job at America’s third-largest defense contractor. Jonathan worked taxing 12-hour shifts starting at 6 a.m. at a Northrop Grumman plant in Magna, Utah, earning about $24 an hour. He had used the money to buy his mother a new roof; he’d been hoping to still buy her a deck.

Witnesses would later tell investigators from the Utah Occupational Safety and Health Division (UOSH) that the area of building 2440 where his body was found at the end of his shift had a history of gas leaks. Employees even knew about the leaks on the day of the deaths: According to the UOSH report obtained by Inkstick through a public records request, Steinke and a coworker, Ken Tran, who would also perish there, had been in the same area on the morning of their deaths, accompanying a maintenance crew to examine pressure switches to see if that was what was causing the leak of argon. The gas, used for welding, is heavier than air and displaces oxygen.

Before they died, Jonathan and Ken each walked down four flights of stairs alongside an autoclave, a vessel used to subject materials to high pressure and heat. A former coworker said it looks like a giant, upright pipe. They reached an underground area that workers called the “pit,” from which they could look up and see the bottom of the autoclave and perform work on the electrical connections and steel tubes on it. There was a barricade at the stairway entrance and a sign that read: “Confined space entry can be fatal. Entry by permit only,” according to UOSH. The sign notwithstanding, UOSH later fined Northrop Grumman for having reclassified the area as a non-permit space; the permit designation would have required the company to perform a series of controls and safety measures to protect employees, such as atmospheric testing and providing workers breathing equipment. (A spokesman for the Utah Labor Commission, Eric Olsen, said that Northrop Grumman is appealing the UOSH citations. The company did not respond to phone calls and emails with detailed questions from Inkstick, including why it is appealing. The adjudication process is ongoing, and there has been no final finding of negligence.)

Exclusive: Read UOSH’s citations here and report here.

Two coworkers later told police they had expected to see Jonathan and Ken in the locker room or showers during shift change; when they didn’t show up, they went searching for them. They swept building 2440 twice and couldn’t find their coworkers; that’s when one noticed that the machinery Jonathan and Ken operated appeared to be in the middle of a leak safety check. He stepped down into the pit and immediately noticed the smell of argon, he told police. He ran out to call for help while the second coworker then tried to descend into the pit to rescue Jonathan and Ken; that employee started to get dizzy within seconds, turned around and crawled up the final steps gasping for breath, according to the police report; his colleague told UOSH that he had to pull him to safety. On the staircase next to Jonathan and Ken’s slumped bodies, witnesses told UOSH they saw a pair of sonic ears, a device a former employee described to Inkstick as headphones and a ray gun-like instrument used to listen for the hissing sound of leaks.

Julie was in bed at 8:30 p.m. and feeling like Jonathan should have been home already when her other son heard a knock on the door from police. She was numb in the hours after learning of her youngest child’s death, she told Inkstick. A supervisor attempted to comfort her, she said, telling her that Jonathan and Ken “were making the hypersonic missiles that were to defend our country” and that “they were heroes on the other side” of this life.

“My thought was, well, why didn’t you protect him?”

Former Employee: Same Building Evacuated for Gas Leak in 2022

Jonathan and Ken died on Jan. 30, 2023, but Inkstick Media is reporting their names and cause of death for the first time.

The company never publicly revealed their identities or cause of death, contributing to an air of secrecy that Julie said bothered her. MK Fletcher, safety and health specialist at the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, told Inkstick that every workplace fatality is individual and it is best to ask families their wishes, and that families tend to want their loved one remembered as a person with a name. She added that sharing workers’ names after they have died on the job helps to humanize the loss and keep the worker’s death from “fading away into the background.”

In a brief statement broadcast on local television in Salt Lake City, an unnamed Northrop Grumman spokesperson was quoted saying that the company was not releasing details of the deaths, “out of respect for the privacy of the employees and the families.” A similar statement about privacy was made in a GoFundMe, which requested that users donate to the families of the deceased but named neither the workers nor the relatives who would receive the funds. One local reporter who arrived at the gates of the plant and photographed emergency vehicles thronging the area tried fruitlessly over the following days to get more information. He penned a short article three days later: “Authorities provide no answers in deaths of 2 West Valley Northrop Grumman employees.”