I met Rani (not her real name) in Adilabad district of Telangana in South India. It was late Spring of 2014: The clear blue sky contrasted against the rugged, dusty red landscape of rural Telangana dotted by bright yellow bushes. Adilabad, and its neighboring districts were once strongholds of Maoist mobilization in India. I traveled through Telangana, my enthusiasm occasionally marred by excruciating dry heat, hearing firsthand accounts of fierce left-wing peasant uprising in the region.

It is important to highlight that informal networks grow in the shadowy grey zone of state-insurgency interface, which we unsee because of our black and white conception of legal/state and illegal/insurgency. I met many ordinary people in conflict zones, who live one foot in insurgency and one foot in the state.

Back in the 1940s, landless and land poor peasants in the region, mostly lower caste and Dalits (formerly untouchable), rose in violent rebellion against the local landlords and money lenders. Although this uprising was prematurely suspended by the leadership of the Communist Party of India after India became independent in 1947, the region subsequently witnessed successive bouts of Maoist agrarian insurrection through the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, punctuated by some phases of setback along the way. Although the uprisings locally targeted feudal landlords, the Maoist leadership had the larger goal of overthrowing the Indian state. By 2006, the Prime Minister of India Manmohan Singh designated the Maoist party as “the biggest internal security threat that the country has ever faced.”

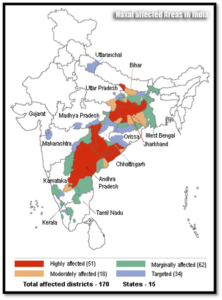

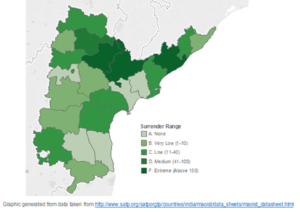

As spectacular acts of violence against security forces, political parties, police stations and other public properties got them national and international attention, many Maoist rebels also quit the insurgency. These desertions cannot be explained in terms of decline of the insurgent organization because, as evident in the recent strike against Indian security forces in April 2021, the Maoists continue to thrive in their strongholds. There is an interesting spatial variation in Maoist exit: Many more rebels quit the insurgency in their strongest pockets of influence in Telangana than in other conflict zones in the North. For example, between 2006–2012, 780 Maoist rebels quit in the state of Andhra Pradesh (of which Telangana was a part) compared to only 54 in the North Indian state of Jharkhand, even though the organizational strength of the highly centralized Maoist party and conflict intensity — measured in terms of casualty and number of Maoist incidents — were comparable in both insurgencies.

Even though law and order in India is managed independently by each state, the anti-Maoist counterinsurgency is monitored and directed by the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) in New Delhi. The federal government applied a two-pronged policy that combined repressive and developmental measures across “worse-affected” districts. For example, the Integrated Action Plan (IAP) launched by the previous government combined various employment, infrastructure and welfare schemes with building fortified police stations and launching an all-out offensive against the Maoists by central military and paramilitary forces. The current government replaced the IAP with Special Central Assistance (SCA) and Civic Action Program, which offers various welfare activities including electricity, schools, employment and infrastructure in Maoist-affected areas, while also targeting their top leadership and eliminating their urban support base. As part of its COIN strategy, the Indian state also offered lucrative surrender and rehabilitation packages for Maoists to quit the insurgency.

Even though law and order in India is managed independently by each state, the anti-Maoist counterinsurgency is monitored and directed by the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) in New Delhi. The federal government applied a two-pronged policy that combined repressive and developmental measures across “worse-affected” districts. For example, the Integrated Action Plan (IAP) launched by the previous government combined various employment, infrastructure and welfare schemes with building fortified police stations and launching an all-out offensive against the Maoists by central military and paramilitary forces. The current government replaced the IAP with Special Central Assistance (SCA) and Civic Action Program, which offers various welfare activities including electricity, schools, employment and infrastructure in Maoist-affected areas, while also targeting their top leadership and eliminating their urban support base. As part of its COIN strategy, the Indian state also offered lucrative surrender and rehabilitation packages for Maoists to quit the insurgency.

I wanted to find out for myself if the government strategy to wean rebels away from insurgency was working. What better way to do that than ask the rebels? I was able to do exactly that when a field research fellowship allowed me to spend 18 months in the conflict zones in North and South India.

WHAT TOOK ME TO TELANGANA

There were two arguments behind the two-pronged counterinsurgency that aims to win the hearts and minds of the ordinary people in conflict zones. First, the Indian state hopes that the cost of rebellion will increase if it cracks down on rebels with more effective repressive measures. The second argument focused on the opportunity cost, concluding that an increase in wages, educational and employment opportunities will make conflict less attractive for the local community by increasing potential earnings that they would lose because of conflict. However, neither state capacity as evident in counterinsurgency measures nor insurgent organizational strength could explain why retirement would vary sharply across adjacent districts within the same states. In addition to the North-South variation highlighted above, this district-level variation is interesting because various measures of state and insurgent capacity do not vary significantly across adjacent districts. For example, as shown in the map below, some districts in Telangana had very high retirement while other adjacent districts recorded very low retirement during the same time. Other Maoist-affected states in the North exhibited the same spatial pattern.

In addition to the state and district level variation in retirement, the other aspect of the puzzle that enthused me to plan a field trip to rural Telangana was the difference in post-retirement trajectory of rebels in the regions: Retired rebels in the North, few as they were, stayed around state capital and joined the machinery of electoral politics, either as candidates or as hired hands and strongmen of politicians. In Telangana, I met former Maoists who are integrated into a wide variety of professions except electoral politics. Many former Maoists in the South are now professors, journalists, singers, activists, lawyers, farmers, real estate brokers, insurance men, bus drivers and so on, but they have not joined electoral politics.

In addition to the state and district level variation in retirement, the other aspect of the puzzle that enthused me to plan a field trip to rural Telangana was the difference in post-retirement trajectory of rebels in the regions: Retired rebels in the North, few as they were, stayed around state capital and joined the machinery of electoral politics, either as candidates or as hired hands and strongmen of politicians. In Telangana, I met former Maoists who are integrated into a wide variety of professions except electoral politics. Many former Maoists in the South are now professors, journalists, singers, activists, lawyers, farmers, real estate brokers, insurance men, bus drivers and so on, but they have not joined electoral politics.

I was interested in meeting these retired rebels in Telangana as well as in the North (in the states of Jharkhand and West Bengal especially) and hear it all from the proverbial horse’s mouth. How do rebels quit an extremist organization and return to the same political system that they had once tried to violently overthrow? This is a significant question in counterinsurgency policy as well as in the broader context of pacification of insurgencies, and I did not know how to answer this question without asking the rebels themselves. I wanted to look beyond the two-pronged counterinsurgency policy, and went to the field with the intuition — reinforced by my preliminary statistical analyses — that retirement is a locally embedded process, and the local grassroots civic associations play a role in facilitating it.

MEETING RAJU AND RANI

I vividly remember that bright sunny afternoon when I met Rani for the first time. I was there to meet her husband Raju (not real name), who was a former Maoist and had been the district secretary of the Maoist group Peoples’ War Group, but had quit the insurgency a few years back. I had prepared a list of former Maoists who had surrendered across Telangana from local newspapers, and Raju was among the first few of the 102 open-ended conversations I had with current and former Maoist rebels in North and South India. Rani smiled at me from the kitchen; as she made tea for me, her silver anklets and glass bangles made the familiar jingling sound. That day another family in the neighboring village had just received the news that their son, a Maoist soldier dispatched to the neighboring state, had been killed in an exchange of fire with security forces. I met many who knew this dead rebel, and recounted how many families in the village had earlier lost their loved ones in this decades-long insurgency. Some of them showed me garlanded photographs of their loved ones who had died. Others reminisced how Maoists, in their battle fatigues, frequented these villages until a few years ago, demanding food and shelter or trying to recruit local men and women.

As Raju reminisced how he had joined the Maoists at the age of 16, the conversation often veered to loss and grief that has scarred his people. The region is most well-known for being the supplier of India’s IT workforce around the world. Many, however, do not remember that Maoists had carved out “liberated zones” (pockets of Maoist control) across Telangana, recruiting many leaders and cadres from the engineering colleges. One remnant of Maoist governance are the tombs they had built to honor their dead comrades. I saw some of these modest structures, now shrouded in thorny shrubs and animal excrement, standing as dilapidated reminders of forgotten martyrs. Rani served tea, and perhaps to change the tone of conversation, asked me where I was from and how I found them. I showed them how I made a list of retired Maoists from various local newspapers in Telangana. Raju also pulled out a dusty file, and pointed to some old newspaper clippings, showing him “surrendering” arms to local police and administrators.

When a Maoist rebel disarms and returns to the mainstream, they often make headline news in local newspapers, and the newspapers carry a customary picture of the rebel with surrendered weapons and flanked by local police and civil administrators who take credit for facilitating pacification of insurgency. In one such newspaper clipping, Raju pointed to another former rebel standing next to him: A frail woman with short pixie hair and eyes cast down. She stood supported by wooden crutches under her arms. Raju introduced her as his comrade and commander in the Peoples’ Liberation Guerrilla Army (PLGA), who had been shot and injured during an attack she led against the police and security forces a few months prior. Rani, with a shy smile, slightly lifted her saree to point to the bullet that was still lodged in her left ankle, right under the jingly silver anklet. This was an unexpected turn that, like many other of my field experiences, jolted me out of my preconceived notions about strong, progressive women who risk their lives to fight for their revolutionary cause.

Rani, and many other women and men I met in rural India during my fieldwork, challenged what I read in books and changed how I wanted my thesis/book to look like. My book, Farewell to Arms, was born in the field, and I wrote it with one aim: To depict how Raju, Rani, and many others I came to know first joined an armed insurgency and finally left it to return to the same state they had once wanted to violently overthrow.

THE THEORY BEHIND GIVING UP ARMS

When I went to the field, I read the Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration literature that advocates providing direct incentives to rebels in the form of cash, jobs, or vocational training to lure them out of violent groups. The democracy promotion literature, on the other hand, recommends luring rebels away not with financial incentives but with offers of political power in democratically elected government, which would make them stakeholders in the system that they would want to protect rather than overthrow. As neatly intuitive these arguments are, I realized that they are based on an untested assumption that rebels can be enticed to leave their comrades, their life’s work, and primary identity with offers of money and political power. Rebels like Rani, Raju and many others in North and South India merely wanted to return to the quiet anonymity of “normal” life. I wanted to hear more about Rani’s experiences in the Maoist movement, but she refused. When I went back to meet Raju a few more times, Rani cooked lunch for us. Gradually our exchanges transitioned from smiles punctuated by long awkward silence to a camaraderie between two women, who were both new mothers, and loved spicy tamarind, crisp cotton sarees and bright rangolis (a sidewalk artform in rural India). She shared many stories of her life and introduced me to many other women combatants. But that’s another story for another time.

In my book Farewell to Arms, the theory is quite simple: Often rebels cannot quit even when they want to because they are afraid that they would be killed, either by the landlords they had targeted during their insurgent career (as is generally the case in the South) or by their former comrades who condemn their retirement as an act of betrayal (as is generally the case in the North). More than post-retirement livelihood provisions that policies focus on, retired rebels decide whether or not they quit extremism based on the ease with which they can lay down their arms without getting killed in the process. State surrender policies that focus primarily on cash rewards and employment opportunities fail to address this fear. Rebels admitted that the looming threat to their lives presented a predicament far more pressing and proximate than the predicament of finding a post-retirement livelihood — or life before livelihood, as Rani simply put. One predominant and recurring theme in my conversations with retired rebels was that they believed that while they might lose their lives, the Indian state would not lose anything if it failed to keep its side of the bargain and protect retired rebels. This, I argue, creates a problem of credible commitment, which is resolved locally through informal exit networks.

In the book, I discuss how informal exit networks, initiated by retired rebels tapping into their personal connections, offer alternate enforcement mechanisms that ensure that retired rebels do not get killed, successfully in Telangana, but not so much in the North. For example, when Raju wanted to quit, he reached out to his family, who secretly convened with local journalists and civil liberty activists. His preliminary network, operating secretly, slowly expanded to include other prominent actors like activists, police officers, politicians and bureaucrats, who were committed to safe return of former rebels. The exit networks, carefully curated based on personal trust and reputation of the actors, worked in semi-secrecy, to identify potential threats to retired rebels. They negotiated a rapprochement between Raju and the local landlord family that Raju had attacked during his insurgent career, through both side payments to the landlord family (license to a gas station, in this case) and trust networks (persuading the widow of killed landlord to “forgive” Raju).

My fieldwork shows that informal exit networks flourish in the South where grassroots associational life is vibrant, but not in the North where civic associations are weak and sparse. Thus rebel retirement is a locally embedded process, and the counterinsurgency leviathan is an adequate policy response when the goal is to wean rebels away from extremism. In addition to individual-level initiative, structural factors like local caste and land relations play a role in the process, primarily by determining the strength of grassroots civic associations, which provide not only the physical space but also pre-existing linkages of trust required to germinate and nurture informal exit networks.

It is important to highlight that informal networks grow in the shadowy grey zone of state-insurgency interface, which we unsee because of our black and white conception of legal/state and illegal/insurgency. I met many ordinary people in conflict zones, who live one foot in insurgency and one foot in the state. These are the people who fortified exit networks; they also played a crucial role in demanding and organizing a peace talk between the rebels and the state in Telangana. It is in these gray zones that grassroots associations foster informal exit networks in semi-secrecy, not entirely unknown to the state. Not only the rebels and civilians I met in conflict zones, but also former bureaucrats, found it unexceptional and mundane that the local politicians, police and bureaucrats often willingly cooperate and collaborate with local rebel groups to maintain peace and stability. To me, an important finding of this research is that in postcolonial context informal institutions are not necessarily competing with state goals, of which clientielism and corruption are familiar examples. The informal exit networks performed a complementary function of filling in the gap by addressing contingencies that formal surrender and rehabilitation policies failed to do. My future research plan builds on this idea of informal sources of state capacity in India.

GOING BEYOND INDIA

The ability of the Indian state to withstand successive violent and non-violent turbulence is an interesting puzzle, particularly given the general consensus on low state capacity of India. Much like the wise men describing the proverbial elephant, there isn’t a consensus on the institutional character (how it looks) and functional capacity (what it does) of the Indian state. If we focus on security response as a measure of state capacity, the gray zone — made of clandestine and semi-secret ties among state, rebel and civilian actors — might appear as an unnecessary anomaly softening the state.

The Indian state is indeed a large, soft sponge. Many insurgencies have relentlessly punched on it with many different demands. But these punches never cracked the state. They only left temporary dents, and the spongiform state managed to fall back in shape. How can we theorize this spongiform state? Do ordinary people in conflict zones, who, the state knows, selectively collaborate with both the state and the insurgents in the treacherous terrains of conflict zones, strengthen or weaken this state? How do we tap the creativity, agility, agency and dynamism of these people into bolstering grassroots peacebuilding? Many ideas generated in Farewell to Arms are from India, including the central theory of credible commitment problem plaguing rebel exit and its resolution in the gray zone of state-insurgency interface. Yet, the theory can be applied to conflict zones beyond India.

My primary motivation in this book, however, was to unequivocally report the stories that Rani, Raju and many others in India generously shared with me. I hope policymakers keen on pacification of insurgencies, in India and beyond, find them useful.

Rumela Sen spends most of her time reading and teaching politics and policymaking at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. In her spare time she reads old and new fictions written in English, Bengali, Hindi, and Nepali. The pictures in this essay are from her fieldwork in India.