“We Didn’t Start the Fire” is a column in collaboration with Foreign Policy for America’s NextGen network, a premier group of next generation foreign policy leaders committed to principled American engagement in the world. This column elevates the voices of diverse young leaders as they establish themselves as authorities in their areas of expertise and expose readers to new ideas and priorities.

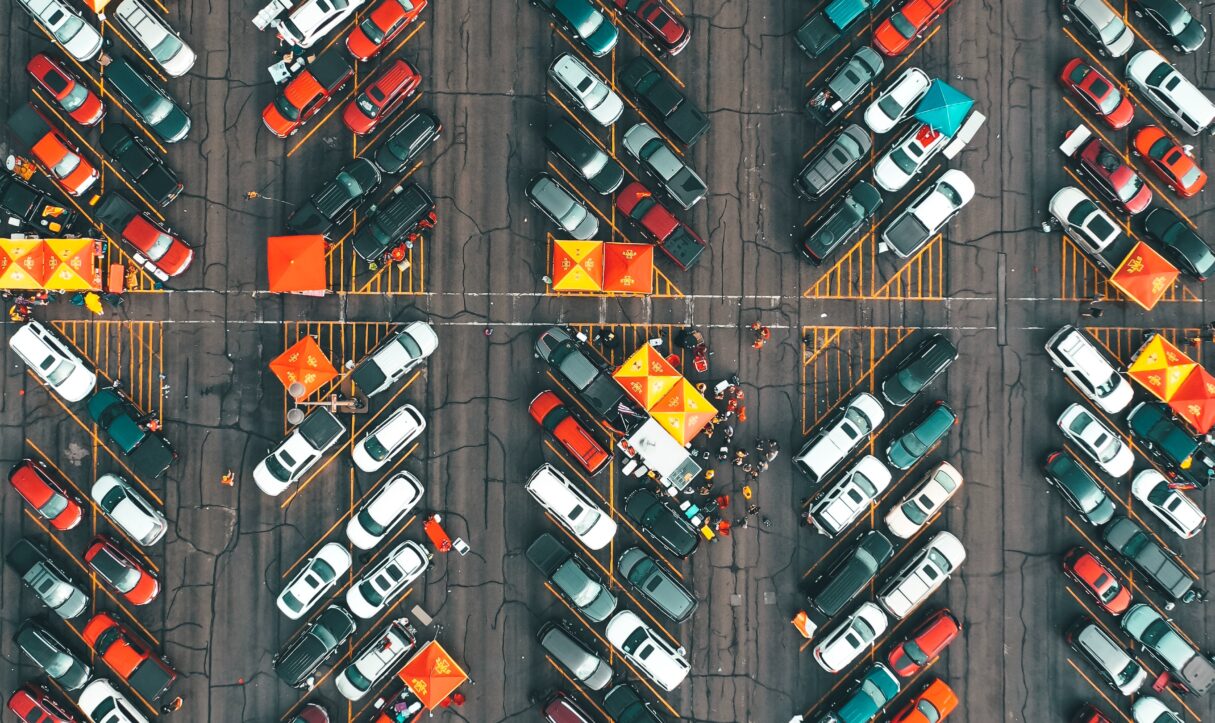

Good drivers check their blind spots. Otherwise, roads become especially treacherous. Now, as the United States shifts from an era of global primacy to an era of competition, its addiction to the automobile should be regarded as a blind spot in national security.

Indeed, car dependency warps US foreign policy to discount mounting dangers, abandon principles, concede political victories to hostile powers, and rationalize military overreach. To the rest of the world, each of these deviations of character is noticeable and exploitable. To guard against these risks, reducing car dependency ought to be acknowledged as a national security imperative and at the same level as building ships, missiles, or cyber defenses — and should be invested in as such.

Opportunity Costs and Geopolitical Risk

Car ownership has become a de facto prerequisite for Americans to access the labor market and engage in civic life. In choosing to make communities car-dependent, the artificial interest in keeping cars affordable tends to overwhelm true US foreign policy priorities.

The most obvious example is climate mitigation. Climate change is the most significant physical threat to US territory. Yet, a plurality of domestic emissions still come from the transportation sector. Car-centric planning then enables sprawling development, which increases emissions from the residential sector. In trade, US car imports contain 3.8 times more embodied carbon than its exports, which enables other developed countries to continue torching the climate. Ultimately, these emissions undermine US leadership by contributing to the loss and damage of climate-vulnerable countries — many of which boast emerging markets, developing democracies, and strategically significant geographies that the United States could benefit from. For example, the United States has already directly caused $257 billion in climate damages to India and $124 billion to Indonesia. The longer it takes to decrease emissions, the more rapidly these costs will increase.

The most immediate example is the sustainability of US support for Ukraine. Following Russia’s invasion, a world addicted to oil struggled to absorb the price shock. American gas stations were a significant outlet for the pain. High gas prices proved to be salient — and, by extension, hampered public willingness to support Ukraine indefinitely. Even when support had been galvanized to its highest point, more than one-third of Americans would have opted for affordably fueling their car over defending a democracy against an existential threat. This implies that, for many car-dependent Americans, accepting a premature and unjust peace had quickly become preferable to gaining the leverage necessary for truly neutralizing Russian aggression at the negotiating table.

Rather than alleviating the pressure on critical minerals by reducing car dependency, which would stabilize relationships and help avert conflicts, the United States maintains a tone of intervention.

The most disappointing example is the Biden administration’s engagement with Saudi Arabia. In 2019, Biden expressed intent to make Saudi Arabia a pariah for its violence and human rights abuses. However, the embargo on Russian oil began making car dependency untenable at home. So, in July of 2022, Biden justified reengagement with Saudi Arabia to “stabilize oil markets.” In October 2022, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) instead slashed oil production by 2 million daily barrels, and Biden has yet to meaningfully respond to the insult. This dependency-driven escapade has been damaging to US values and credibility.

Devil in a New Dress

Car dependency elicits resource gluttony, which can unleash wrath. In 2022, the United States consumed a total of 7.4 billion barrels of petroleum. Cars alone required 3.2 billion barrels, comprising 43% of consumption. This level of demand grants immense power to the states that export oil. Specifically, exports create economic growth and geopolitical leverage for producers, which insulate these states against sanctions and backlash from abroad. Insulation untethers national restraints, enabling aggressive and coercive behavior. Russia exemplifies such “petro-aggression.”

This untethering effect is not exclusive to oil. In transitioning to a dependency on electric vehicles, the effect may just as easily apply to critical minerals. Worse yet, the production of critical minerals is even more geographically concentrated than oil, limiting alternatives in the event of aggression.

In terms of demand, a conventional car requires 34 kg of copper and manganese, and an electric vehicle requires 207 kg of copper, manganese, lithium, nickel, graphite, cobalt, and other minerals. China controls 60% of the world’s production of these resources, including 95% of the world’s manganese. China has already established export conditions on gallium and germanium, both used in electric vehicles. The move has been described as “just a start.” Amid heightening tensions, the prospects of China resorting to either economic warfare or EV-emboldened aggression are all too real.

In response to China’s present mineral advantages, reestablishing those supply chains through closer and friendlier nations has some merit. However, this does nothing to address the phenomenon of dependency-driven production untethering national restraints. Latin American lithium producers are already assuming a more assertive economic stance with plans to establish a cartel similar to OPEC. The cartel would manipulate lithium prices according to producer states’ political preferences, which will often run counter to US national interests.

The United States — which is a petrostate itself, and which has intervened in Latin America repeatedly — may be more likely to extend its military once again if events in the region complicate its electric vehicle dependency. Suppose, as in the Chaco War, mining exports form intractable territorial ambitions and lead to conflict between Latin American states. Or suppose, as in the Falklands War, an untethered power from the east grows disenchanted with resource cooperation and aggresses a Lithium Triangle state. As opposed to previous periods of instability, the United States would be depending primarily on this region for resources that undergird the basic ability to move its own goods and people.

Rather than alleviating the pressure on critical minerals by reducing car dependency, which would stabilize relationships and help avert conflicts, the United States maintains a tone of intervention. Analyzing China’s critical mineral interests in Latin America, US Southern Command stated, “These actions have the potential to destabilize the region and erode the fundamental conditions needed for quality private sector investment.” Given the larger context of US-China competition, rhetoric such as this establishes a pretext for intervention or at least a show of force. Ironically, the US military preoccupied in the Western Hemisphere may be precisely what best serves China’s interests in the Indo-Pacific.

Car Optionality as National Security

To be clear, cars are not the problem. Neither are all the people who enjoy cars. Dependency on cars is the problem. So, Americans should continue to build, buy, and export cars. Meanwhile, the United States should re-design streets with haste to value modal equality and resilience in transportation systems. After all, car dependency is a product of deliberate policy choices, and so can be undone by deliberate policy choices. To this end, there are actions policymakers can take immediately.

Specifically, Congress can pass the bipartisan Yes In My Backyard Act, which promotes transit-oriented development of dense, mixed-use buildings. Additionally, the People Over Parking Act strengthens private property rights by eliminating parking requirements. Together, these bills would create powerful new incentives to design Complete Streets nationwide.Until then, dependency engenders vulnerability. Car dependency makes the United States less prosperous and more exploitable. These are traits of an insecure nation. Yet, the current levels of financial investment and political seriousness given to reducing this dependency fall far short of more conventional security programs. It is time for this to change.