BLUF: The American middle class, while still in existence, has dramatically changed over the decades. What once worked well for achieving household success no longer guarantees security — at home or abroad.

I remember watching American Dreams on NBC with my mom in my early teenage years. If you haven’t seen it, the show follows the Pryor family in Philadelphia, PA during the mid-1960s. The main character Meg (Brittany Snow) dances on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. It’s the quintessential story of the so-called “American Dream” — a family of four in suburbia, navigating the ebbs and flows of the middle class. I loved that show, mostly because I definitely wanted to be like Meg, but also because it romanticized the American Dream.

We’ve all heard it before, no matter where you come from — if you work hard, anything is possible in America. The American Dream equation was (supposed to be) pretty simple: hard work = a job and place in the middle class. However, more and more often these days, we hear in the media and from politicians that the middle class is deteriorating. So this BLUF is tackling a pretty big question: does America still have a middle class to dream about?

DEFINING THE MIDDLE CLASS

To be clear, the US government does not define or prescribe a dollar amount specifically to the middle class like it does for poverty. For example, in America, 2020 poverty is defined as a maximum household income of $26,200 for a family of four — this set amount is used as a qualification for a variety of government-provided or subsidized programs (think: food stamps and Medicaid). But an annual amount is not given to define the “middle class.” Instead, it turns out there are at least a dozen different ways to define “the middle class.” According to the US Census Bureau, the average American median income in 2019 was $68,703. According to Pew, in 2018, just over half (52%) of all US adults live in middle-income households, while 29% live in lower-income households, and 19% in upper-income households.

But the middle class isn’t just a number, it’s also an idea. According to a Pew poll, in 2015, people who self-identify as “middle class” have a wide range of household incomes: between $30,000 to $100,000+ annually. And according to a Northwestern Mutual (“SPEND YOUR LIFE LIVING!”) study featured by CNBC, more than 70 percent of Americans consider themselves to be a part of the middle class. Despite expert fluxing definitions, “middle class” is more often a reflection of the way we view ourselves, given about 18% more Americans self-identify as middle class than Pew defines as such.

BLUF activity: This Pew calculator shows you what class you fall into compared to both other adults in your area and among American adults overall. It also shows you how you tee up compared with folks of similar education, age, race/ethnicity, and marital status.

TODAY’S MIDDLE-CLASS DEEP DIVE

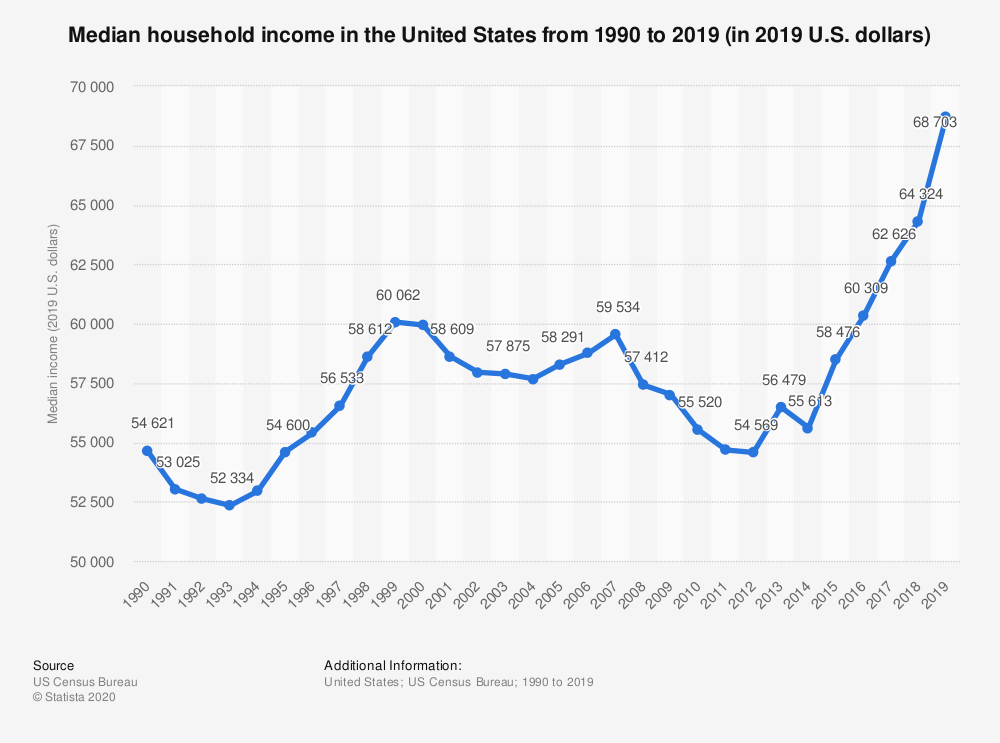

At first glance, things look pretty good for today’s American middle class. One chart shows that the median income in America from 2000 to 2019 has generally increased, with some exceptions, from $54,000 to $68,000 — a $14,000 increase in 19 years ain’t bad.

The deeper you look, however, the more the facade of the “thriving middle class” wears off. Because what that income increase doesn’t account for is its failure to keep pace with the costs of being middle class. To demonstrate this, take a second to visualize what a middle-class family is likely to have. Maybe what you pictured was a white picket fence house, a family of four, parents putting a kid through college or saving for it, a car, and a Hawaiian vacation.

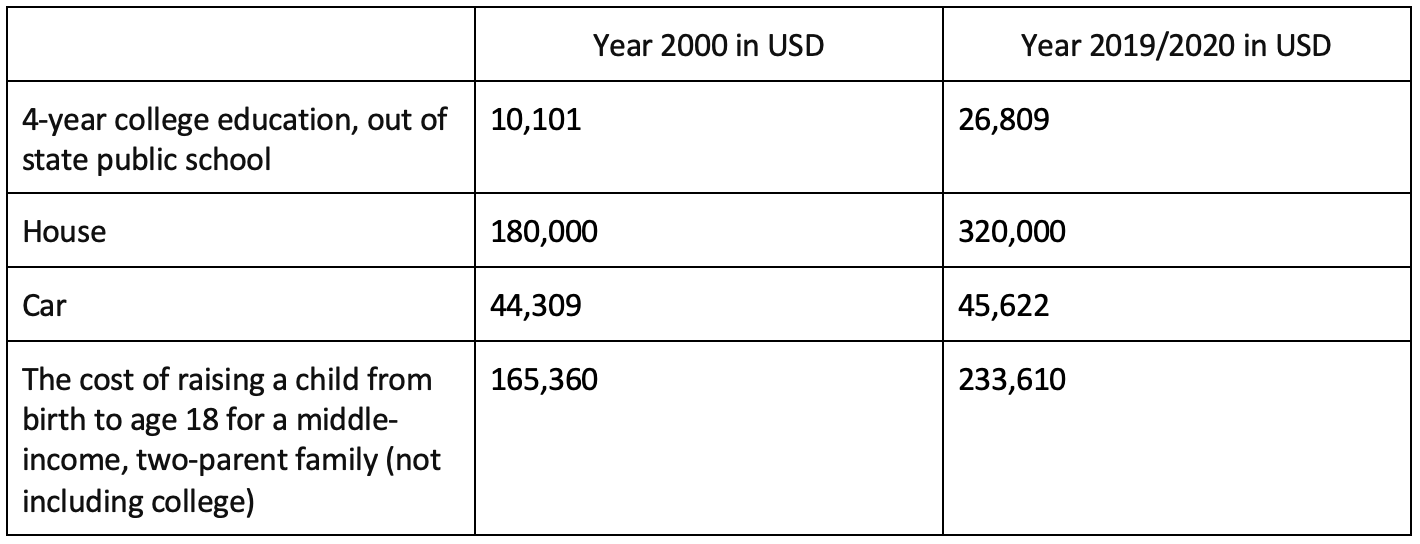

Let’s look at how some of those costs varied from 2000 to 2019/2020:

This chart supports claims made by Investopedia that the dollar’s buying power is significantly less now than it was 20 years ago. Put bluntly, that $14,000 steady increase is failing miserably to match the pace of inflation, and no longer covers the cost of a middle-class lifestyle. According to CNBC, “Middle-class life is now 30 percent more expensive than it was 20 years ago. The cost of big-ticket items like college, housing and child care have risen precipitously: The cost of public universities doubled between 1996 and 2016 and housing prices in popular cities have quadrupled.”

Remember that simple equation from earlier? Hard work = a spot in the middle class? Yeah, well over time, that equation became hard work + a college degree = middle class. And we already know how much a college degree can cost you. Apparently, back in 1970, only 26% of the workforce had education beyond high school but by 2018 that percentage had risen to 68%. And even though more people are going to college, only 27% of jobs require higher education, which means a bunch of people are shelling out money unnecessarily. This is further compounded by the fact that the “add college and stir” idea isn’t paying off. The unemployment rate for college graduates has remained the same or gotten worse since the 1990s, and 2020 was absolutely abysmal for recent college grad job prospects. Not only are the unemployment rates for college graduates bleak, but a study by Harvard Business Review showed, “median earnings for recent grads were no higher in 2018 than they were in 2000 and 1990 (after adjusting for inflation).” A livable income is no longer a given post-college.

It’s also extremely important to note that what’s considered middle class in rural Arkansas, isn’t synonymous with what you’ll see in middle-class metropolises — this one aspect alone dramatically widens both the definition and wage gap.

Take for example: me. When I moved to DC in 2017, with a Master’s degree in hand, my fellowship paid $36,000 before taxes. That was not poverty level, and in some states might have gotten me pretty far, but in DC — LOL. There were months when I ate nothing but ramen, lived on credit cards, and worked an extra job just to make ends meet. My story is not dissimilar to many other millennials in metro areas with advanced degrees — and I was one of the lucky ones without college loans.

It is also proven that where you end up financially still depends a lot on factors out of someone’s control, like how/where you grew up, your race/ethnicity, and family status. Improvements have been made, let’s not downplay that, but as one report says, “the chance that a child born in the bottom quintile will make it to the top quintile as an adult ranges from around 4% in Charlotte to 13% in San Jose.” If you start at the bottom, hard work isn’t always enough to get you closer to the top.

One other key difference in today’s middle class vs. previous middle classes is the existence of a savings account. The middle-class ideal, according to some, isn’t just about obtaining a house and car in the here and now — it’s also about planning for the future. So, middle-class families typically want to have both a savings account for unforeseen accidents/medical bills/when the refrigerator kicks the bucket, and a retirement account. While savings in America steadily increased between 2000 and 2010, the most recent decade saw a drastic savings dip.

According to one survey, more than one in five working American adults don’t set aside any of their annual income for short-term or long-term goals. Of those saving, 20% save only 5%; 28% save 6-10%; and 16% are saving 15% or more. But according to experts, that probably isn’t enough to cover both an emergency fund and a retirement fund. When asked what is the hold up on saving more, Americans say it’s just “expenses.” Another very common statistic you may have heard is that many Americans don’t feel they could cover an unexpected $400 expense — 39% to be exact, with 12% saying they definitely couldn’t make it work and the remaining 27% saying they could but would need to use a credit card, loan, or sell something. For many folks, the financial security of the middle class is no longer all that secure.

A VERSION OF VANISHED

In sifting through mounds of data, one thing seems certain: America still has a middle class but the way it, and the American Dream, looks has changed dramatically. Perhaps, hard work will give you your own idea of the middle class, but that life now also likely includes periods of unemployment, living paycheck to paycheck, sacrificing vacation time for retirement, and so on. It’s not just that everything is more expensive, it’s also that how the middle-class fares now varies wildly based on where you live, if you had to take loans out for college, and, if after all of those more expensive expenses — there is enough left in the paycheck to save.

As best I can tell, the idea of the “disappearing” middle class has less to do with an actual vanishing act and more to do with how unrecognizable and indecipherable that class has become.

As best I can tell, the idea of the “disappearing” middle class has less to do with an actual vanishing act and more to do with how unrecognizable and indecipherable that class has become.

FOREIGN POLICY DOTS

None of this is great. For every tiny datapoint of hope I found about the middle class, pages and pages of dismal data brought me back to the realization that America’s new middle class isn’t really working. More often than not, the discussion surrounding the future of the middle class focuses on domestic politics, with a strong emphasis on education and economics. And that makes sense intuitively. But there are huge parts of the conversation that have been left out. One of those parts is how the unrecognizable middle class impacts our national security and foreign policy. So, let’s connect some dots.

Plain and simple: when things aren’t going well at home, you’re unlikely to perform well in the classroom or at work. Same can be said for the middle class and foreign policy. For one, funding international priorities is not only harder to swing when financial times are tough, but it’s even tougher to convince taxpayers they should spend their hard-earned dollars on funding early childhood education programs in Afghanistan when those same taxpayers are working their asses off and still don’t feel secure. When your own house is on fire, the general rule of thumb is you buckle down and put out that blaze first. The problem with this narrative in a globalized society is that so much of America’s economy, growth, and security is now (for better or worse) inextricably linked with foreign relations.

Take oil prices: As you likely know, gas prices fluctuate regularly and one thing the middle class has in common is, usually: a car. I can remember times when “filling up” cost more than $4 a gallon and days when it was less than $2. Let’s face it: America runs on oil, and Dunkin. What you might not know is that over decades, America has faced periods of both energy security and insecurity. And while the debates about oil independence and energy alternatives rage on, for the foreseeable future, America will require foreign oil. The link between our relationship with countries and the price of oil is a direct result of American foreign policy.

Take troop bases abroad: Have you ever sat down and really thought about how military families are able to live overseas on American bases? Guess what! Foreign policy. The United States has nearly 800 military bases in more than 70 countries and territories abroad. Again, there is some debate here on why we need so many but the general idea is: these bases allow America to project power, influence events abroad, and place us closer to potential areas of conflict on speed dial (think closer to Russia/China/the Middle East vs. traveling from North Carolina).

Take the American farmer: Bad relationships with foreign partners aren’t empty threats, they impact middle-class America in very tangible ways. For example, a multi-year trade war to bring manufacturing back home by the Trump administration resulted in China placing tariffs on more than $70 billion of American products, inadvertently wreaking havoc on farmers. But in January 2020, the US and China agreed to a deal in which China committed to increasing its imports of US goods, including agriculture products. And sure enough, in October 2020, the US Department of Agriculture announced that China was on track to import a record $27 billion in ag goods from the US in fiscal year 2021 — becoming the top foreign export for American farmers.

Take targets for disinformation: As I discuss in another #BLUF, disinformation is considered one of the top threats to America’s national security. Both domestic and foreign-waged disinformation campaigns have similar goals, including causing internal division and chaos in the United States, and shaking the confidence of the American electorate in their political leadership and government. The more insecure Americans feel, the more susceptible to disinformation we are, and the less secure we become — a vicious cycle.

Foreign policy and national security don’t have pause buttons. America can’t just pull a Ross/Rachel and “take a break” from international relations to sort out the middle class. On the contrary, our wellbeing at home is heavily influenced by relations outside our borders: from manufacturing to healthcare, and oil to defense.

The data doesn’t lie. It’s true, the American middle class no longer looks the way it did during the heyday of American Bandstand. The data hints that it’s likely because our individual success is not a magic, one-size-fits-all equation. But maybe it never really was and that’s why we assumed it had vanished.

And that’s all for this one, babes.

No pressure. No bullshit. Just, THE BABES BLUF.

THE BABES BLUF (bottom line up front) is a different kind of current affairs and lifestyle blog that talks about issues in a way women (and men!) can relate to and enjoy. We believe fundamentally in providing readers with facts to encourage the formulation of individual opinions. Because we recognize that you’re busy (with jobs, babes, families/friends, and self care), #THEBABESBLUF gives you a quick one or two liner with what you really need to know. Then, when you have a little more time, we break it down using facts and citations.

To read more from THE BABES BLUF, visit www.thebabesbluf.com and subscribe to never miss a #BLUF. Be sure to also check us out on Twitter or Instagram @thebabesbluf. For more THE BABES BLUF pieces, see here.