“That concept US citizens will never understand,” Speaker Kedi said. “Your very vein as a Marshallese, the fabric of yourself is interwoven to that land. You are that land. Take that away from them, and you are killing their entire beings as Marshallese. Psychologically, socially, and everything else.”

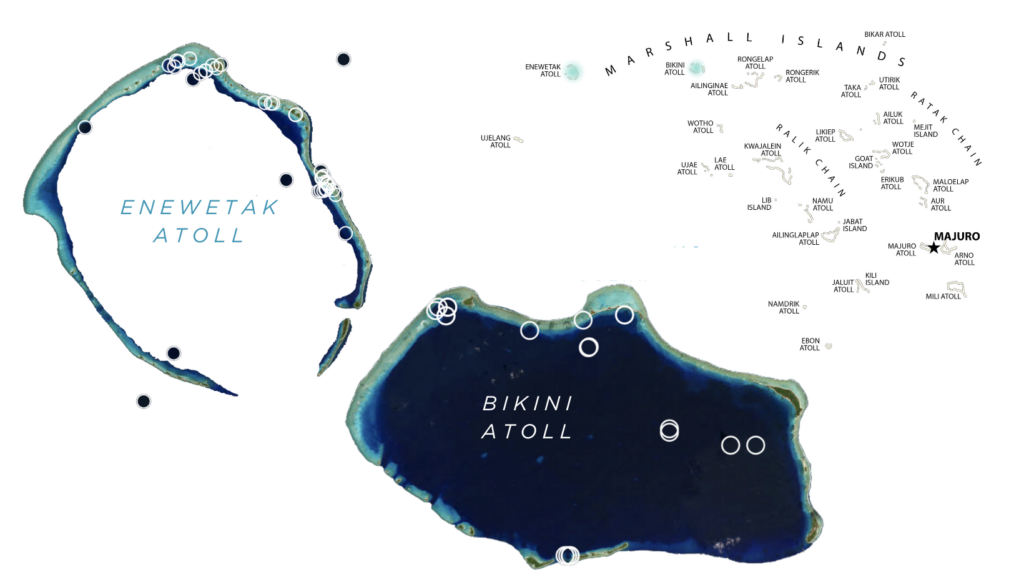

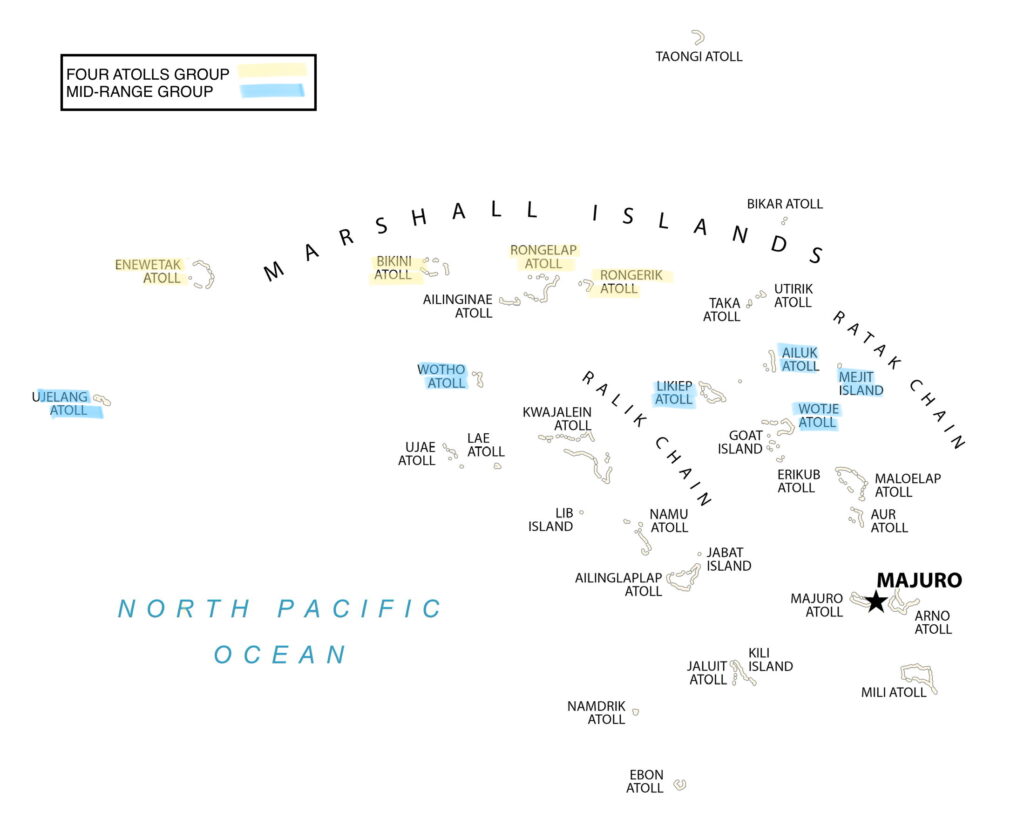

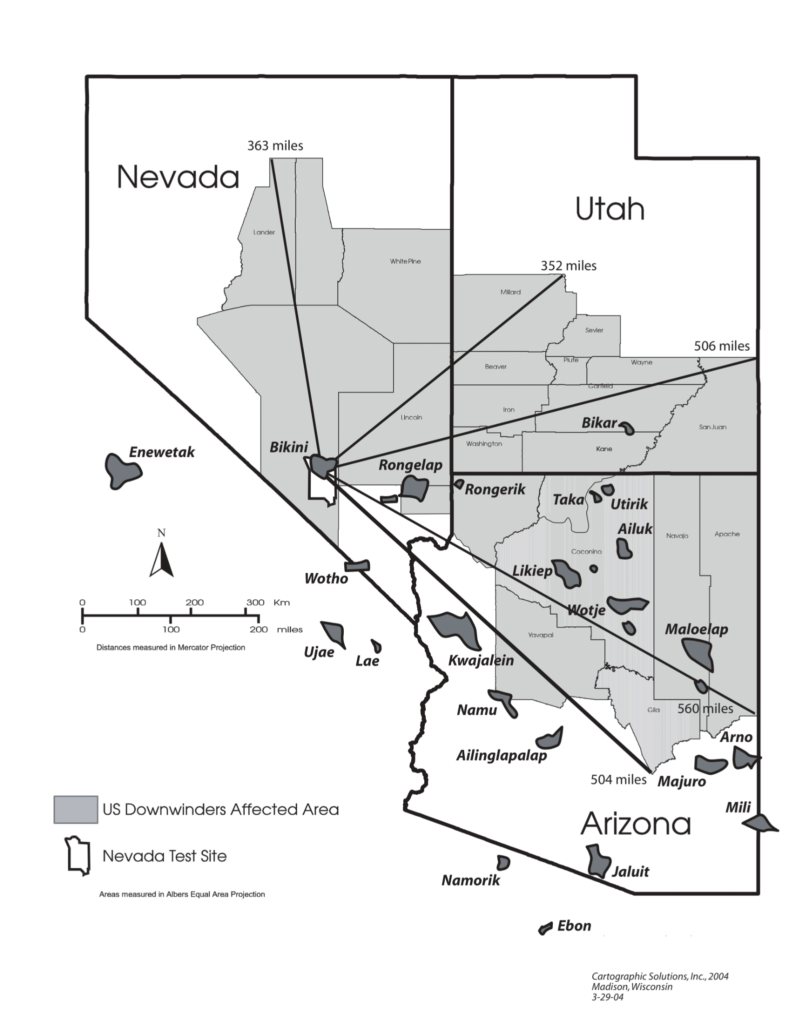

Maybe even more so than the inherited health issues, every future generation carries this cultural trauma, Kedi says. Generations of Marshallese have had their land taken away. Underfunded clean-up efforts in the 1970s that failed to totally rid the contaminated atolls of residual radiation have ensured few returners. Though small a population of caretakers exists on Enewetak to upkeep the Runit dome, scientists hold that residents should not return to Bikini and Rongelap until thorough clean-up efforts are completed. The cleanup efforts were begun in the 70s but later abandoned, leaving residents in permanent limbo.

“We are nomads.” Mina Titus’s husband, Jemlok Titus, said. “No home.”

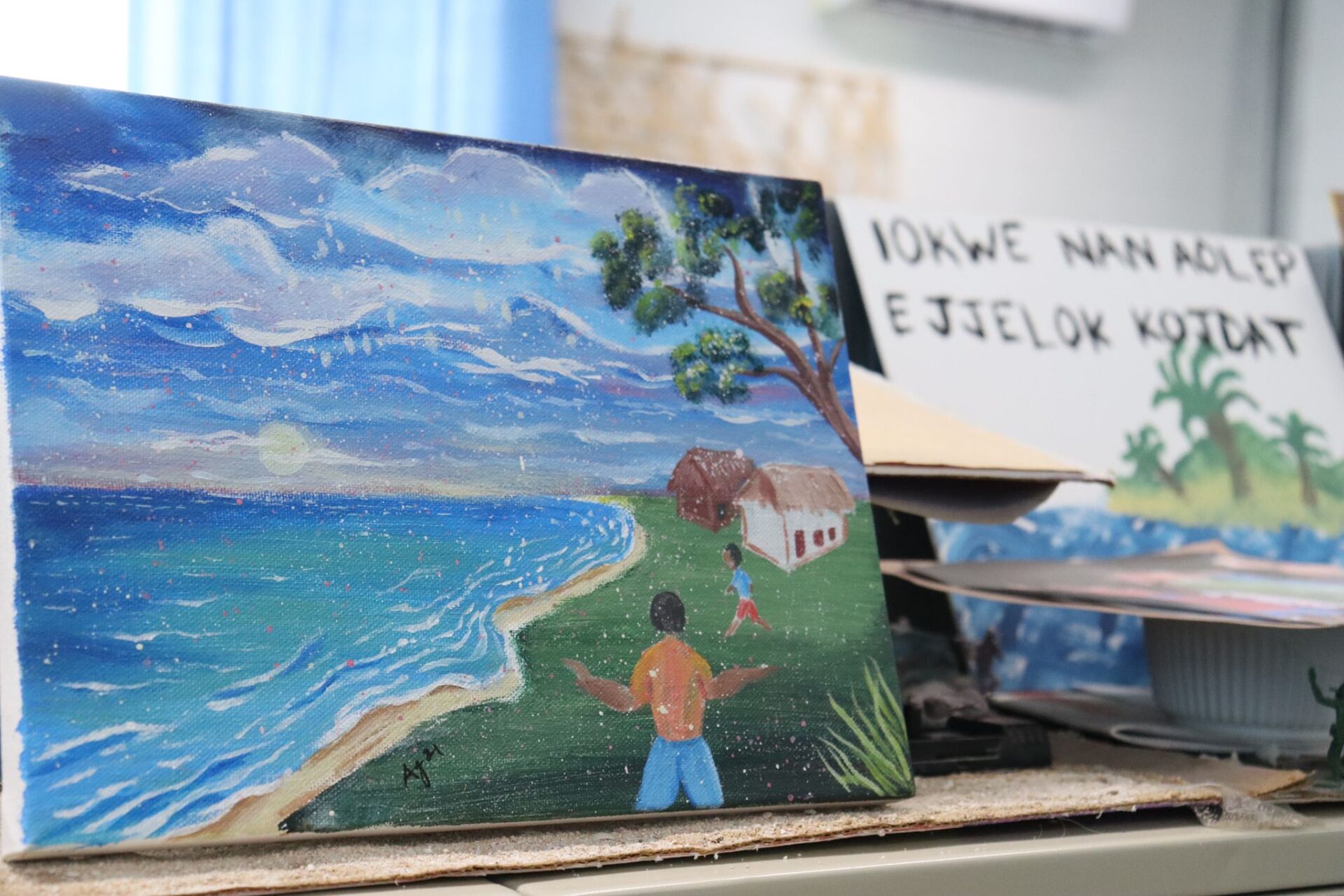

Mina Titus sits outside her house in Majuro, remembering her real home an ocean away. Her grandchildren play nearby under the low-hanging leaves of an ancient breadfruit tree. They have never even known a place to miss.

“I really miss the beauty of Rongelap,” Mina Titus said. “Over there we had freedom. It’s been our home.”

She paused for a long moment. “I know I cannot go back.”

This story was reported with the aid and contributions of Hilary Hosia from the Marshall Islands Journal.

Correction issued 12/5/2023: This piece was updated to reflect that Utrik was evacuated after the Bravo test.

While many advocates and experts sat in conference room “Regency A” at the Hyatt on Capitol Hill, attending the Carnegie Endowment’s biannual Nuclear Policy Conference, a couple blocks away at 11:30 am Eastern Standard Time on Thursday, Oct. 27, 2022, President Joe Biden released his 2022 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR).

In a cohort of some of the foremost minds on these issues, phones started to vibrate and screens light up. For a second, folks directed their attention away from an ever-so-chilling panel on the potential for Nuclear Armageddon. Some people left the room, and some contacted their teams to make sure that their statements and experts would be quoted. But then just like that, the conference, the panel, the moment, returned to exactly what it had been before that fateful drop: just another Thursday.

The disappointing nature of the NPR is not really a surprise, especially for those of us who have been working for a world free from nuclear weapons.

Some will argue the fever in the air died down in anticipation of networking sessions, panels, and keynotes that would directly link to the drop of the NPR. Others might say that the drawn-out NPR process itself dimmed the excitement in the room — that the anticipation had been lingering for months, and the release of the NPR lost its gusto. I think the reason the moment passed so quickly was because the NPR itself was so unsurprising.

Despite promises on the campaign trail and earlier signs that this NPR might adopt No First Use, sole purpose, or any other forward-moving doctrine that would show the difference between this and the last administration, this review didn’t do that. In this “unprecedented time,” with regard to President Vladimir Putin’s saber-rattling; the ongoing negotiations of treaties like The Compact of Free Association and the call for nuclear justice for impacted communities such as The Marshallese; and even just the realities of inflation, where American families are feeling the pain of rising costs, the NPR focuses on modernizing the US nuclear arsenal. Specifically, the NPR keeps the United States on track to spend $634 billion in taxpayer dollars over the next decade on unnecessary weapons as Americans continue to experience more of the same.

NOT WAITING ON POLICIES

The disappointing nature of the NPR, however, is not really a surprise, especially for those of us who have been working toward a world free from nuclear weapons. There are individuals, organizations, and communities who have already stopped waiting on policies and are creating forward-thinking strategies to achieve the world they want to see.

There are several community groups that advocate for their people, who have faced (and continue to face) inequitable policies, such as the Marshallese Educational Initiative, which encourages Marshallese and non-Marshallese members “to provide venues for Marshallese community members to share their own stories and causes.” Grant agencies and organizations alike have also increasingly focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion and issues of justice, highlighting those who have faced injustice due to US nuclear policy, either in the form of nuclear testing or nuclear weapon modernization. In July 2022, the Ploughshares Fund announced it would provide 16 grants focused on three categories: challenging racism and white supremacy in nuclear policies and institutions; building actionable connections between nuclear weapons issues and other issue areas; and examining and dismantling the military-industrial complex. For those of us who have been active in this field, these three categories are seen as necessary steps on the path toward a nuclear weapons-free world.

Finally, the activists who continue to show up to protests, answer emails, call their legislators, sign petitions, and keep the conversation going on social media have not been deterred by any NPRs, or any other unclassified national security strategy documents. Every day all of these people show their resilience as they work to create a more just, prosperous, and equitable future. In a way, they are the real heroes.

WORKING TOWARD A JUST WORLD

What changed with the release of this report?

I, for one, know it doesn’t change how I will do this work and fight to get to zero nuclear weapons. I will continue working with a team of changemakers who are equally as strategic, driven, passionate, and motivated as I am to create a world of equity, justice, and prosperity rooted in possibilities beyond the bomb. And one day, this world will exist. Why am I so optimistic? Because people are at the root of the nuclear weapons complex. People are making the decisions, people are the ones impacted, and people are the ones who are deserving of a world that makes them feel both safe and secure.

There is still a lot to be done. I implore this community, full of activists, organizers, academics, and policy experts, to engage in the tough conversations that go beyond “hard security” issues. Collectively we need to make engaging in intersectional and diverse conversations a priority and then align strategies and take action.

It is our job as people who work toward better forms of national security and foreign policy to keep communities safe. When things “don’t go our way” or stay the status quo, don’t get mad or throw in the towel. Get like Stacey Abrams: recoup, reorganize, find your partners, be bold and resilient, and most importantly, continue the work. People deserve it.

Mari Faines (she/her) is the Partner for Mobilization at Global Zero; a social justice, diversity & equity activist, and former podcast host. Her work specializes in nuclear intersectionality, conflict resolution, transitional justice, and racial and systemic disparities.

Correction 11/01/22: This article incorrectly stated that the United States would spend $1.8 trillion on nuclear weapons over the next decade. It has been updated to the correct figure which, according to the latest estimate by the Congressional Budget Office, is “$634 billion over the 2021-2030 period.”

Since the development of nuclear energy in the mid-20th century, Native American reservations have been subjected to thousands of tons of toxic nuclear waste, with dangerous consequences for health, the environment, and tribal sovereignty. The disproportionate concentration of nuclear waste on Native lands is not a coincidence. Instead, it reflects a targeted effort by the US government to saddle Indigenous communities with “the most hazardous material ever created by humanity or nature.”

For example, over 500 abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation have poisoned residents’ drinking water and caused elevated rates of kidney failure and lung disease for generations. Members of the Yakama Nation in southeastern Washington, home to the Hanford Nuclear Site, experience high amounts of thyroid cancer and congenital disabilities. And the Western Shoshone tribe, which has been exposed to significant nuclear fallout from decades of nuclear testing on its land (known as “the most bombed nation on earth“), suffers disproportionate leukemia and heart disease rates. These are just a few examples of the devastating health impacts caused by what activists and scholars have aptly described as “radioactive colonialism.”

The disproportionate amount of nuclear waste on Native land can be primarily attributed to the many legal, economic, and regulatory power imbalances between Native American tribes and the federal government.

Taking the Land

Understanding the roots of environmental injustice in Native communities requires considering the US government’s centuries-long history of forcibly dispossessing and displacing Native people. The 1887 General Allotment Act, also known as the Dawes Act, took over 90 million acres of land away from Native American tribes, mostly to be sold to non-Natives. Subsequent legislation, including the Curtis Act, Homestead Act, and Indian Removal Act, further stripped Native Americans of their ancestral land. And in 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act, which cemented the federal government’s authority over Native American tribes and increased tribes’ reliance on federal funds. Since then, US companies that produce hazardous waste have often capitalized on tribes’ lack of sovereignty — operating on Native reservations allows them to face minimal oversight and exempts them from state and local laws.

The federal government has intentionally singled out and targeted Native American reservations as potential repositories for high-level nuclear waste.

Courts have also restricted the ability of tribes to control their land, particularly in cases involving tribal authority over non-Native individuals. For example, in Brendale v. Confederated Tribes and Bands of Yakima Nation (1989), the Yakima Nation contested the ability of members of other tribes and non-Native individuals to develop on reservation land. The Yakima Nation argued that this was prohibited by Indian zoning law, even though it was permitted by the county’s zoning laws. The issue was whether the Yakima Nation had exclusive zoning rights on their land. The Supreme Court decided that the Yakima did not and limited tribes’ authority to regulate development on their land. Issues of jurisdiction and sovereignty on Native land are complex and contested, with many different entities (e.g., the federal government, state governments, and tribal governments) competing to exercise regulatory authority.

As a result of legal and political decisions limiting tribal sovereignty, health and safety standards on Native reservations are often less restrictive than on non-Native land. This is especially important when it comes to the nuclear industry. Years of nuclear testing and development on tribal land (as well as several resulting accidents) have led to major radioactive exposure and few consequences for its perpetrators.

Becoming Sites for Nuclear Waste Disposal

The federal government has intentionally singled out and targeted Native American reservations as potential repositories for high-level nuclear waste. After years of struggling to dispose of the United States’ rapidly-accumulating radioactive waste, Congress passed the Nuclear Waste Policy Act in 1982. This law authorized the creation of Monitored Retrievable Storage (MRS) facilities to store the nation’s nuclear waste — and Native American reservations were targeted as ideal sites for MRS facilities. A 1991 Public Citizen and the Nuclear Information & Resource Service report explains that Native land was targeted partly because the nuclear industry could “hide from environmental regulation and widespread public opposition behind the shield of tribal sovereignty.”

Several Native American tribes have sought to store nuclear waste on their land, pointing to the economic benefits of MRS facilities. The Office of the Nuclear Waste Negotiator, a short-lived federal agency tasked with finding communities willing to host MRS facilities, offered tribes thousands of dollars in grants just to consider the idea and promised million-dollar payments if tribes would go through with it. Many tribes, including the Mescalero Apache and Skull Valley Goshute, applied to the program, focusing on the financial advantages instead of the environmental risks caused by radioactive waste.

Some government officials claimed it would be preferable for Native American tribes, and not other communities, to store the nation’s nuclear waste. For example, David Leroy, the Nuclear Waste Negotiator from 1990–1993, argued (to much backlash), “Because of the Indians’ great care and regard for Nature’s resources, Indians are the logical people to care for the nuclear waste.”

Others claimed that allowing tribes to choose to apply to nuclear waste storage programs demonstrated respect for and deference to tribal sovereignty. But anti-nuclear advocates characterized this view as ignorant of the coercive history and inherent power disparities between tribes and the federal government.

Nuclear dumping on Native land can be seen as a continuation of the United States’ long history of exploiting and dispossessing Native people.

The government’s strategy (later adopted by private corporations) was widely criticized for capitalizing on and exploiting economically disadvantaged Native American communities, with the highest poverty rate out of all racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Financial incentives for nuclear waste storage on Native land have been described as “a form of economic racism akin to bribery.” In addition, establishing temporary or permanent nuclear waste repositories on Native land could make it more difficult to sue nuclear waste manufacturers for damage caused by these facilities because of the regulatory conflicts mentioned above.

Perhaps the best-known example of nuclear encroachment on Native land in recent decades is the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository, a proposed permanent storage facility on Western Shoshone land in Nevada. The Western Shoshone people have a long history of exposure to radioactive material. For years, the US government conducted nuclear tests at the Nevada Test Site, releasing hundreds of tons of radioactive fallout onto Native land. When Yucca Mountain was chosen as a site for the nation’s principal repository of nuclear waste, the Western Shoshone were never consulted, asked for consent, or acknowledged as the original owners of the land.

Since then, the project has progressed considerably but faced numerous roadblocks, including litigation, resistance from Native activists, and opposition from the state of Nevada. Opposition to the repository has been driven by concerns about the potential health and ecological impacts — including groundwater pollution, radiation exposure caused by possible earthquakes, and severe health risks such as cancer and respiratory illness.

Resisting Nuclear Dumping on Native Land

As of 2022, the Biden administration is opposed to continuing development on Yucca Mountain, but until Congress amends the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, Yucca Mountain will continue to be the proposed site for the nation’s primary nuclear waste storage facility.

Although the Yucca Mountain project has not yet come to fruition, many examples of environmental contamination caused by nuclear waste on Native land exist. Radioactive material and other hazardous chemicals were dumped into Washington’s Columbia River for decades, contaminating the Chinook salmon, which the Yakama Nation tribe has historically relied on as a primary food source. In the Navajo Nation, radioactive material was used to build homes and schools. The land of the Ute Mountain Ute tribe, next to the only functioning uranium mill in the United States, has been found to have groundwater contaminated with high acidity levels and dangerous chemicals such as chloroform.

Nuclear dumping on Native land has been met with intense resistance for as long as it has been occurring. There are several ways in which Native leaders have attempted to fight back and achieve justice. For example, they have advocated for expanding and renewing the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, a federal law providing compensation to workers harmed by nuclear exposure.

Tribes, sometimes supported by states, have also pursued litigation against government and private companies for the environmental and health risks caused by nuclear waste. These lawsuits have faced many procedural barriers and some have been dismissed. In contrast, others have resulted in favorable settlements, although no amount of money can thoroughly remedy the harm inflicted by nuclear waste. Other advocacy efforts include pressuring the government to clean up nuclear waste sites and urging more research on the health impacts of nuclear waste.

Advocates have described nuclear waste on Native American reservations as a textbook example of environmental injustice: the disproportionate exposure of marginalized communities to environmental harm. Nuclear dumping on Native land can be seen as a continuation of the United States’ long history of exploiting and dispossessing Native people. Addressing it will require a comprehensive approach that centers the voices and experiences of Native communities.

This piece is published in collaboration with Outrider Foundation, a nonprofit media group that publishes commentary on security issues, public policy, and social justice.

Trigger Warning: There are mentions of interpersonal, structural, and mass racialized sexual violence.

The United States’ intensified grip on the Asia-Pacific continues to render the Pacific — known as “The Ocean Bride of America” — its feminized, orientalized captive of war. Where the United States has identified China and its achievements in building a world without dependence on US capital (such as China’s Belt & Road Initiative and lifting 800 million people out of poverty) as its primary target, it escalates for hot war through its pivot to Asia, its 400 military bases, and more specifically, its aggressive agenda for nuclear warmongering. However, for women, girls, and gender non-conforming peoples in the imperialized Pacific, nuclearization has always been an imperialist tool for gendered violence. For them, the war(s) in the Pacific never ended.

To understand the consequences of nuclear warfare in today’s militarized Asia-Pacific, we need to explore how mechanisms of nuclear warfare impact women, girls, and gender-nonconforming peoples.

COLONIAL LEGACIES

The United States first developed its nuclear infrastructure in the Pacific. Alongside genocide of Indigenous peoples in Turtle Island for settler-colonial land acquisition, military settler-colonial ambitions took the United States across the Pacific again with World War II. As a result, the Pacific became captive stations of both hyper-exoticized extermination and recreation.

As the United States repurposed its first 19th century colonies in the Pacific — Hawaii, Guam, and the Philippines — to serve as geostrategic “stepping stones” to China, islands became ports for nuclear submarines, yearly naval exercises, and the development of military technology. Simultaneously, the tourism and sex tourism industry was developed to sanitize military presence on the islands. The cultural prostitution of once sovereign places like Hawaii made Indigenous women into exotic, sexualized sites for rest and recreation. This combination of US’ dispossession of land and resources and the violent hypersexualization of native women enabled the conditions for which Native Hawaiian women continue to be most at risk of sexual violence, domestic violence, and sex trafficking today.

The US also obtained strategic trusteeships such as the 1947 Pacific Proving Grounds initiative, which converted Micronesia and their sovereign land, water, and people into testing grounds for nuclear waste, bioweaponry tests, and the securitization of its on-call naval capacities. Exposure to high to low-dose contamination since then have made Marshallese women victims of congenital disabilities, cancer, and other chronic damage to reproductive health. Alongside recreation, the Pacific became a site of aqua nullius genocide.

WHAT “PROTECTING” THE PACIFIC REALLY MEANT

As the United States expands its weapons arsenal through its most recent $7.1 billion Pacific Deterrence Initiative, it recycles its Cold War motto for “protecting” Pacific nations against the “threat” of Chinese encroachment. Just like it did during the Cold War, this Initiative repurposed US bases in Guam, South Korea, Okinawa, and more with new weapon programs meant to threaten North Korean and Chinese nuclear defense arsenals. In Guam and South Korea, the newest Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system is capable of taking down Intercontinental ballistic missiles and utilizes tests that displaces productive land and air resources. Korean women and elders, who bear the consequences of militarized land and resources, remain at the forefront of anti-THAAD protests and demands.

The demonization of nuclearized “rogue states” such as North Korea, Iran, and Syria simply relieves the US of its role in creating the conditions for the realities that forced these states to adopt such weapons in the first place.

Of course, the expansion of military bases has also always meant the sexploitation of working-class women for white sexual imperialism, reifying US intervention “for their own good and the good of civilization.” From the UN-sanctioned 1950 invasion of Korea (the carpet bombing of North Korea totaling greater attacks than on Germany and Japan during World War II) to the US war in Vietnam and Southeast Asia (with over 8 million B-52 bombs dropped, equivalent to 100 times the damage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined) the United States established agreements with sub-imperial nations for Rest and Recreation sites, institutionalizing the sexual slavery of women economically and physically coerced into the trade. Aside from dehumanizing women of the “enemy” for the purposes of motivating military extermination (i.e., the My Lai Massacre in Vietnam and the use of pornography in US invasions of Iraq), women across Asia were made into hypersexualized, docile, disposable objects for the sexual and political desires of colonizer men.

With survivors as young as 9 months old, US military personnel have had a long history of assaulting Okinawan women and girls, faced with little to no legal repercussions. In recovering Southeast Asian nations, the commodification of women through the mail order brides industry, militarization of transnational domestic labor arrangements, and sex buying at or around (former) military bases reveal how much national production continues to be bound to the murders of girls and children in neocolonial agreements. That the militarization of a society transpires into multiple forms of violence against women across borders; it is no accident that national sexual assault organizations report that Asian and Pacific Islander women are more likely to be sexually assaulted by white assailants.

IMPACT OF SANCTIONS ON WOMEN IN THE PACIFIC

Coming full circle, the nuclearization of the Pacific must be understood as a means to fundamentally contain any peoples who dare to challenge 20th-century debt-trap capitalism. Assertions of national self-determination and alternative nationalized production capacities must be quelled. In order to justify the use of sanctions as warfare, the demonization of nuclearized “rogue states” such as North Korea, Iran, and Syria simply relieves the United States of its role in creating the conditions for the realities that forced these states to adopt such weapons in the first place.

Without yet taking into account US violations of nuclear deterrence initiatives, such as the Iran Deal, sanctions lay siege to a nation’s capacity to eat, produce, and survive through deadly restrictions that debilitate the country’s access to the world market. Working women, who are responsible for the reproductive and productive capacities of the economy, thus bear the brunt of sanctions’ consequences. For example, sanctions faced by North Korea have caused feminized production in the textile industry to be undervalued, and cut off from profits of the international market. Unable to access a stable source of income and thus economic autonomy, women become prone to other forms of gendered violence. In a weakened economy with dwindling food and medical access, it is no wonder 99% of pregnant women are unable to access medical aid needed for pregnancy.

In Iran, a fossil fuel-rich country, sanctions have made it ironically impossible to import the capital they need to access their own natural resources, driving down their general economy and driving up state restrictions to make up for its underproduction. Again, inflationary rent and unstable incomes have made it impossible for women to work toward anything but survival. The state’s welfare capacity to provide transportation, maternity leave, and childcare was limited as women who were previously able to struggle for things like girls’ education under the Islamic Republic of Iran faced difficulty accessing literacy with newly imposed state restrictions.

REFRAMING NUCLEARIZATION

It was and continues to be anti-imperialist feminists on the forefront of imperialized nations who identified the United States as the largest threat to women, life, and humanity. They remind us that fundamentally, we need to struggle for a world without nuclear weapons.

But we need to think about nuclearization as a historical, geopolitical process that brandishes violence against women to accomplish its larger objectives: US ambitions for its capitalist world order. The late Haunani Kay Trask, Native Hawaiian independence activist and feminist, pinpoints US imperialism as the root of the racialized, gendered nuclear crisis best:

“Only the dismantling of the United States as we know it could begin the process of ending racism…

I join with Toni Morrison, one of the finest writers of our age, in asserting that I am not American. Nor, I might add, do I want to be American. Those who believe as I do, especially those who did not become part of the United States voluntarily, will surely nod in agreement.”

Victoria Huynh is an aspiring educator and writer, learning to put anti-imperialist feminism(s) into practice. She is also a fellow at Beyond the Bomb.

Correction 07/13: The original article has been corrected for clarity.

Soon after Russian forces had taken control of the Chernobyl site on Feb. 24, 2022, SaveEcoBot, an online radiation monitoring site in Ukraine, recorded an exceptional jump in the radiation counts of 65,500 nSv/h at the site at around 9:50 pm (local time). Another concerning increase of 93,000 nSv/h was recorded at 10:40 am on Feb. 25, 2022. While the rise in radiation counts was troubling, the absence of updated radiation data for two days after the increase was even more disturbing.

The unprecedented large-scale nuclear catastrophe at Chernobyl in 1986 released a large amount of radioactivity, and was even detected as far as 8100 km (more than 5000 miles) away, at Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute in Japan, on May 3, 1986, just a week after the beginning of the nuclear catastrophe. Even though the radioactivity gradually decreased over the weeks, Japanese scientists documented another increase at the end of May 1986. The Japanese scientists concluded that the radioactivity from Chernobyl had circulated the earth and returned to Japan. The UN Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation assesses that “radionuclides from the Chernobyl release were measurable in all countries of the northern hemisphere.”

The world mustn’t experience this kind of radioactive fallout again.

CALLING FOR IMMEDIATE ACTION

After Russian forces took over the nuclear facility at Chernobyl, and without any subsequent data that suggested the radiation levels went down later, concerned activists and scientists met online. They shared concerns about the situation at the Chernobyl site and other nuclear facilities in Ukraine. After the meeting, our group, the Manhattan Project for a Nuclear-Free World that focuses on raising awareness about the consequences of nuclear energy and nuclear weapons, and a handful of concerned groups around the world, drafted and submitted an open letter to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on Mar. 1, 2022. We sent it to the IAEA’s Board of Governors before their emergency meeting on the situation in Ukraine, which was scheduled for Mar. 2, 2022.

The ongoing situation in Ukraine confirms that nuclear reactors and radioactive waste disposal sites could be weaponized or accidentally damaged, which would result in widespread radioactive contamination.

We called on the IAEA to do five things in the open letter. The first was to determine who is currently responsible for the operation and the radiation safety of the Chernobyl site and investigate their degree of technical capability to deal with nuclear emergencies. Second, conduct assessments to identify the necessity to send additional nuclear technicians to maintain the safety of the Chernobyl site. Third, investigate and establish the status of Ukraine’s 15 reactor sites to ensure their continued operation under qualified personnel. Fourth, ensure transparency and protect the right to information of local people by promptly publishing all relevant data and information, in the local language and English, regarding the radiation safety of all nuclear facilities and nuclear power plants in Ukraine. And fifth, request IAEA member states, particularly those who are part of the conflict, to refrain from any military or other action that could threaten the nuclear facilities’ safety in the conflict zone.

In the letter, we also highlighted concerns raised by Beyond Nuclear, a nonprofit advocating for a sustainable and democratic energy future. All nuclear reactors in Ukraine are vulnerable to catastrophic meltdowns even if they are not directly attacked or accidentally hit. And more importantly, a nuclear power plant cannot be abandoned under any circumstances.

WHERE ARE IAEA’S INSPECTORS?

Ukraine has 15 commercial nuclear reactors at four nuclear power plants in addition to the decommissioning reactors at the Chernobyl site.

A couple of days after the letter was published, there was a report that a projectile had hit a building near the Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Station in southeastern Ukraine, which is the largest in Europe and among the 10 largest in the world. There was also news of a nuclear research facility in Kharkiv in the northeast of Ukraine, where radioisotopes for medical and industrial applications were being produced, had been damaged by shelling. Another report documented missiles hitting the site of a radioactive waste disposal facility in Kyiv, the capitol.

In addition to nuclear reactors that could release a large amount of high-level radioactivity into the environment, radioactive waste disposal sites that store highly radioactive wastes, such as spent fuel from nuclear reactors, are also vulnerable to catastrophic radioactive discharge. Spent fuel usually sits in dry cask storage near nuclear power plants in Ukraine. Holtec International, a New Jersey-based company, built Central Spent Fuel Storage Facility inside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone near the Chernobyl site in November 2021 for Energoatom, Ukraine’s national nuclear energy company.

The ongoing situation in Ukraine confirms that nuclear reactors and radioactive waste disposal sites could be weaponized or accidentally damaged, which would result in widespread radioactive contamination. However, despite these concerns, the IAEA could not send a delegation to Ukraine to investigate the situation until late March 2022, when Director-General Grossi traveled to the South Ukraine nuclear power plant. Furthermore, the IAEA could not send a team to the Chernobyl site until Apr. 26, 2022, more than two months after the exceptional radiation increase was detected on Feb. 24, 2022.

Unfortunately, the situation in Ukraine has demonstrated that the IAEA does not have a system in place to send a team of nuclear technicians to facilities to mitigate an emergency. This is an extremely concerning issue, especially as the IAEA-led global nuclear industry promotes nuclear energy as a “peaceful use of nuclear” in politically unstable regions, such as the Middle East, Central Asia, and Africa.

NUCLEAR REACTORS ARE THE REAL THREATS

The concerning situation at nuclear power plants in Ukraine was foreseeable. Nuclear power plants always have risks of terrorist attacks. For example, the 9/11 Commission Report released in 2004 revealed that the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks considered targeting a nuclear power plant near New York City: “…Atta also mentioned that he had considered targeting a nuclear facility he had seen during familiarization flights near New York — a target they referred to as ‘electrical engineering.’”

The 9/11 Commission, therefore, exposed how vulnerable the Indian Point nuclear power plant made New York City. Being only 25 miles north of the city meant that a terrorist attack could impact the 20 million people who live or work within a 50-mile radius of the plant, including people in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. It would also be impossible to evacuate such a substantial number of residents in a timely manner. The movement to shut down Indian Point gained more momentum in the wake of the 2011 nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi in Japan. Thanks to persistent activism by local groups, the last nuclear reactor at Indian Point was permanently shut down on Apr. 30, 2021.

Damaged nuclear power plants or radioactive storage sites could result in a devastating radioactive discharge into the environment, contaminating air, water, soil, and food. In addition, radiation exposure from radioactive fallout will add to human health risks. World War II could have made Europe uninhabitable due to radioactivity for decades or more if they had the same number of nuclear power plants during the war. It is safe to assume that the fear of radioactive contamination is one of the main reasons behind rejecting no-fly zones or expansion of military activities in Ukraine that could escalate to a nuclear war.

We tend to debate about a nuclear war caused by nuclear weapons, but we do not need a nuclear weapon to bring about a catastrophic radioactive impact in the region. Nuclear power plants are pre-deployed weapons of mass destruction that are vulnerable to catastrophic nuclear disasters even if they are not directly attacked or accidentally hit. Loss of electricity or human error has caused a large-scale nuclear disaster, as we have seen at Fukushima Daiichi, Chernobyl, Three Mile Island, and other locations.

THE NUCLEAR BAN TREATY

Professor Robert Jacobs’ research highlights how nuclear energy was created to kill people. The first modern nuclear power plants built at Hanford in Washington state developed the plutonium for the first nuclear testing at Trinity site in New Mexico and the atomic bomb that destroyed the lives and health of people in Nagasaki in 1945. According to Jacobs, nuclear power plants were invented and “developed to produce nuclear weapons for use against a civilian population in war” to kill masses of human beings. Generating electricity, therefore, is a secondary purpose of this technology.

Why do we continue to allow the narrative that erroneously describes the use of nuclear energy as “peaceful” when the origin, existence, and potential of nuclear power are all extremely violent?

Nuclear energy also undermines democracy. Similar to the violent origin of nuclear weapons, nuclear power is deeply rooted in systemic racism and nuclear colonialism, which continues to disproportionately impact marginalized communities of color, Indigenous Peoples, and those with limited resources. For example, uranium mining for nuclear fuel is a highly extractive process that severely affects the health of residents. As a result, a large-scale nuclear accident would disproportionately affect members of marginalized communities, pregnant people, mothers, and children. In addition, highly radioactive waste from nuclear reactors is is planned to be stored in vulnerable communities of color.

On Jan. 22, 2021, the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, also known as the “nuclear ban treaty,” entered into force. It outlawed nuclear weapons under international law for the first time. It also aims to eliminate nuclear weapons by emphasizing deep concerns about the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons, such as exposure to ionizing radiation. The treaty also recognizes the “disproportionate impact of nuclear-weapon activities on indigenous peoples” and the disproportionate impact of ionizing radiation on “women and girls.” Article 6 of the treaty discusses the positive obligations of state parties to adequately “provide age- and gender-sensitive” victim assistance and environmental remediation in communities “affected by the use or testing of nuclear weapons, in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law.” There are 86 signatories and 61 state parties as of Jun. 4, 2022.

The Nuclear Ban Treaty’s humanitarian approach is a progressive shift from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), whose main objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology while promoting nuclear disarmament and nuclear energy. But its stance on nuclear energy will limit its ability to achieve its goals under Article 6 effectively. Furthermore, a part of its preamble states that “nothing in this Treaty shall be interpreted as affecting the inalienable right of its States Parties to develop research, production, and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes without discrimination.” What this really means is that the treaty does not explicitly prohibit providing uranium to nuclear-armed states, even though global uranium trade assists in developing and producing nuclear weapons.

NEXT STEPS

Why do we continue to allow the narrative that erroneously describes the use of nuclear energy as “peaceful” when the origin, existence, and potential of nuclear power contains so much violence?

Since the first nuclear reactor produced plutonium for nuclear weapons to kill civilians in war, nuclear energy inherited its worst violent traits from nuclear weapons. And now, the situation in Ukraine reaffirms that nuclear energy and radioactive waste storage sites could also be weaponized or accidentally cause devastating radioactive fallout in the region, which could impact the health of a large population and future generations.

Before it is too late, we must shift the inaccurate mainstream narrative of nuclear energy from “peaceful” to “violent.”

Mari Inoue is an attorney and co-founder of the Manhattan Project for a Nuclear-Free World, a volunteer-led grassroots group in New York City. She has been active in grassroots movements to educate policymakers and elected officials on nuclear weapons and nuclear energy’s costs, risks, and humanitarian consequences.

More than one year after police brutality and systemic racism led to the murder of George Floyd, the United States hasn’t done nearly enough to combat systemic racism. This applies domestically, but also to the realm of US foreign policy. For far too long, we’ve treated racism and violent white nationalism as solely a domestic issue when in reality, racism is built into the foundation of our nation’s approach to foreign affairs. It’s long past time for us to come to terms with this and actively combat the racism embedded in our foreign policy. That starts with holding our current administration, and ourselves, accountable.

The US has a long history of racism in its domestic and foreign actions. White colonizers destroyed native life and land in the name of “Manifest Destiny.” Anti-Asian sentiment forced hundreds of thousands of Japanese-Americans into internment camps. In the 1970s and 80s, the United States instigated countless conflicts around the globe, supporting ruthless dictators and human rights abuses in the name of containment. In the Trump era, Islamophobia barred Muslim refugees from coming to this country to escape war. America’s Western paternalism and neocolonialism lives on within and outside of its borders. Such racism continues to exist today, often in implicit and dangerous ways.

The historic events of the past year ー worldwide protests demanding that Black lives have and will always matter ー seem to have raised a new sensitivity to racism. However, events in even just the past few months have illuminated the persistent presence of racism and American exceptionalism within our foreign policy decisions.

For instance, at our southern border, the Biden administration engaged in a stealthy “vaccine diplomacy” effort with Mexico. In April, the US promised Mexico 2.5 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine to help combat its crippling COVID-19 crisis, quietly pressing for Mexico to curb immigration to the US in return. Most of those that still embarked on the treacherous journey to make a new life here, including asylum seekers, have been immediately turned away by US Customs and Border Patrol. Conditions at ICE detention centers have always been inhumane, but they stooped to a new level during the pandemic: reports of forced gynecological procedures, dwindling resources, failure to create a socially-distanced environment, and the list of abuses goes on.

Vice President Kamala Harris also delivered a blunt and harsh message to Guatemalans hoping to immigrate to the United States: “Do not come,” she said repeatedly. Her messaging centered around the need for Guatemala to focus on its government corruption and human trafficking issues, as well as limiting immigration to the US. Harris’ remarks implied that many of the issues Guatemala faces are of the country’s own doing, failing to recognize and account for the long history of US intervention in and exploitation of the country. From the CIA’s support of military dictators that conducted genocide during the Guatemalan Civil War to the continued exploitation of Guatemalan coffee planters for large corporations like Nestle, it’s clear that the US refuses to take accountability for its past and present legacy of racism, colonialism, and exploitation.

There is no easy solution to a centuries-old system of unjust and exclusive values built into America’s very foundation. However, individual and systemic changes can create cracks in that racist foundation to create a better, safer future for our country and ultimately our world.

The embedment of racism in US foreign affairs isn’t restricted to just one area, but it’s prominent in the defense and security realm. The Biden administration has made competition with China a cornerstone of its foreign policy, justifying the further bloat of the Pentagon’s budget by making exaggerated claims about the size and scope of China’s military threat. The reality of our comparative military power is indisputable: our deployed warheads are five times that of China’s and our active nuclear stockpile is 11 times the size of China’s. Yet instead of working with China to combat the most pressing issues plaguing the globe — from climate change to pandemic relief — we’ve chosen to pursue a path of competitive realism. This foreign risk inflation, not to mention the racist undertones of rhetoric surrounding COVID-19, has also spurred anti-Asian violence at home. The more we artificially create competition with China, the more we put our own citizens at risk.

Realistically, there is no easy solution to a centuries-old system of unjust and exclusive values built into America’s very foundation. However, individual and systemic changes can create cracks in that racist foundation to create a better, safer future for our country and ultimately our world.

We can start by reframing education surrounding International Relations. Universities offering International Relations courses should take a critical look at their curricula. The role of race and racism in shaping postcolonial global power structures should be central to these courses, not confined to a “special day” to discuss racism, which is all too common. Academic institutions must also improve their hiring processes to significantly increase the racial diversity of their International Relations faculty; the field has been gatekept for white men for too long.

When we invest in bettering the education of those who study International Relations, we invest in better global leaders for the future. This extends to international policy-making and diplomacy, too. In 2018, 81.3% of US foreign service specialists were white, and employees of color were less likely to be promoted than their white counterparts at every rank within the foreign service corps. It’s been long-proven that leaders representing their own communities, who understand their real needs, can affect the greatest change for them. We must advocate for there to be more seats at the table, especially for people and nations that have been traditionally marginalized.

On a national level, it is imperative to place immense pressure on Congress to divest funding from the Pentagon and the United States military and to actually invest in human security— that means taking some of the billions of dollars that are spent on building weapons and reallocating towards expanding public health access, ensuring stable housing for all, combating climate change, and so on. If even a portion of Biden’s proposed $715 billion Pentagon budget was reallocated towards improving the quality of life for Americans, we’d be in a much better state than we are now. Continuing to militarize further will not make Americans safer and will actively work against efforts to achieve racial equality, both at home and abroad.

On an individual level, we need to continue to write, to post, to protest, to have those tough dinner table conversations. And most importantly, we need to listen to Black and brown voices.

We must not allow the social and political momentum created in the summer of 2020 to die. The murder of George Floyd and countless Black and brown people in America, the early and ongoing massacre of indigenous people and resources, the internment of Japanese-Americans, and America’s entire history of colonialism are gruesome reminders of our need to do better and to push our government to be better. Since the effects of racism are often not considered and even hidden within the foreign policy sphere, we must loudly and actively recognize the inextricable ties between domestic racism, American exceptionalism, and US foreign policy.

Rishma Vora is a member of the Center for International Policy’s Summer 2021 Development and Communications Team.

In 1946, the Navy bombed its own ships in the Pacific. Operation Crossroads, which resulted in the exile of Marshallese natives and rendered Bikini Atoll uninhabitable to this day, saw the detonations of two plutonium nuclear weapons of the kind dropped on Nagasaki on a fleet of 96 ships. Live pigs on board, stand-ins for military personnel, keeled over and died. The ships were sandblasted, but the contamination only spread. The least contaminated ships were scrapped and most were so radioactive that they were ultimately filled with barrels of radioactive substance and intentionally sunk. But before these ships’ destruction, they were towed to a historically Black neighborhood in San Francisco called Bayview-Hunters Point.

The city does not emphasize its nuclear history to newcomers. After all, the thought of the military dropping nukes on its own ships and dragging them to a major metropolitan area for what we now know to have been a futile decontamination procedure would not sit well with anxious homebuyers or align with San Francisco’s progressive veneer. California has already pledged to shut down its last nuclear energy power plant by 2024, so many of the city’s residents would like to believe that Hunters Point is a relic of environmental racism and nuclear ignorance. However, the city’s ongoing compliance with housing magnates and Naval contractors in transferring contaminated land for development delivers a particularly painful sting in a county strapped for housing, even if its upper classes are already numb to gentrification. One of its biggest scandals has exposed what might be referred to as a new “nuclear triad” — the Navy, cleanup firm Tetra Tech, and housing development firm Lennar Corporation — that have worked to undermine neighborhood leadership and compound rather than rectify the city’s nuclear legacy.

THE NAVY AND THE CLEANUP FIRM

San Francisco’s nuclear story began when the Navy bought out a private shipyard in San Francisco just before the Pearl Harbor attacks. There, they established the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard. The Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory, one of the first labs commissioned to study radiation, spread radioactivity throughout Hunters Point for years. According to documents declassified in 2001, the lab’s experiments included feeding radioactive liquids to humans and hanging a nuclear isotope that emits X-ray-like radiation in the San Francisco Bay. Outside the lab, decontamination procedures like open-air sandblasting further spread radiation from bombed ships to Hunters Point. An aircraft carrier was moored at the shipyard for years before it was loaded with 48,000 barrels of radioactive waste and sunk thirty miles off the coast. After reviewing “spotty” historical records, the Navy decided against testing 90% of the 883 designated parcels of land at the former shipyard. Later findings revealed that the Navy found “ubiquitous” radiation in certain places when it had expected contamination to be restricted to documented spill locations, so it’s difficult to be certain of the safety of the untested sites.

The Navy has yet to acknowledge the threat of high-level radiation stemming from the many drums of waste produced over the course of the shipyard’s operations, but it has admitted to detecting what it classifies as “low-level” radiation” emitted from radionuclides with short half-lives. However, even low-level radiation can be volatile since there is no safe level of radioactivity. A 2019 city-convened University of California panel supported the Navy’s claim that sampling procedures were sound, but conceded that the Navy misled locals by distributing flyers and other materials saying the site posed no health risks. Even the UC panel’s main assertion defending the integrity of the Navy’s sampling procedures around housing has been shaken by its exclusion of whistleblower testimony and its failure to disclose a potential conflict of interest in the UCSF property next to the shipyard that saw all fourteen employees test positive for toxic heavy metals. Three of the four panel members (the fourth, environmental scientist Kirk Smith, passed a few months after the report’s publication from an unrelated cause) have since expressed regrets about the report, with UC Berkeley Professor Thomas McKone saying of the shipyard’s legacy of misinformation: “We didn’t realize what we were stepping into.” Panel member Professor John Balmes has apologized for his “faulty memory” with regard to disclosure of his past work advising shipyard developers and contended, “We should never have embarked on what we were trying to do, because it was a no-win situation.”

The Navy’s minimization of lethal nuclear operations at Bayview-Hunters Point fit into a larger military pattern of avoiding responsibility for early radiological ignorance, ongoing environmental racism, and the self-sabotaging volatility of the nuclear system in the name of security.

The report’s lack of trust within the Bayview-Hunters Point community and the panel’s retroactive acknowledgement of the community’s contentious relationship with cleanup authorities underscore the need for a community-led initiative with regard to the city’s nuclear legacy and broader civil-military discussions nationwide. The Navy’s minimization of lethal nuclear operations at Bayview-Hunters Point fit into a larger military pattern of avoiding responsibility for early radiological ignorance, ongoing environmental racism, and the self-sabotaging volatility of the nuclear system in the name of security.

MILITARY-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX MEETS HOUSING DEVELOPMENT

Upholding this status quo are two actors — engineering firm Tetra Tech EC and housing developer Lennar Corp. — that have prevented the Hunters Point cleanup from starting a larger conversation about the injustice of the nuclear system. Tetra Tech was contracted to test just 10% of the Hunters Point sites against the political backdrop of the largest redevelopment project since the 1906 earthquake leveled the city. Tetra Tech was to test and clean parcels of land and transfer them to the city. Over 20 years, Tetra Tech managed to transfer just one parcel for the construction of 439 condos before soil samples used to prove radiation levels met cleanup objectives were found to be fabricated. Further investigation revealed that Tetra Tech allegedly fired whistleblowers and hired the son of an RASO site manager in order to convince her to overlook weakened radiation portal monitors. Lawsuits against Tetra Tech resulted in the imprisonment of two supposedly rogue employees, but when a federal judge presiding over the many cases against them grew suspicious, the firm demanded he recuse himself for bias. The government paid $250 million for a botched cleanup, waived Tetra Tech’s $7,000 fine, and rewarded the firm with more cleanup contracts. Aside from the blatant corruption, the Navy violated the Superfund law requiring the use of up-to-date cleaning standards like the EPA’s designated calculation tool and the Navy’s retesting plan centers on cost-cutting rather than human safety, a testament to the coziness of the military-industrial complex.

The nation’s second-largest home construction company, Lennar, was among the top ten spenders on lobbying local politicians in 2015, one year after it launched its third city redevelopment plan near Bayview-Hunters Point where Candlestick Park once stood. Lennar built its fortune converting former military bases into suburban dreamscapes, but in 2008 homeowners in an Orlando development uncovered a buried bombing range complete with live WWII-era rockets under yards and schools. While Lennar contends that they too were victimized by the military’s deceit, the company’s financial stakes in government projects with the Department of Defense, USAID, and EPA are well documented. They paid a whopping $1 apiece for the rights to develop Hunters Point and Mare Island, another Bay Area military base in the working class city of Vallejo. Seeing that they split their profits evenly with the city of Vallejo, Lennar shares its financial stakes in government projects with San Francisco. Dan Hirsch, former director of the UC Santa Cruz Center for Environmental and Nuclear Policy and president of the nuclear industry watchdog Committee to Bridge the Gap, condemned the 2019 UC panel’s review of sampling procedures around Lennar’s Hunters Point development as inextricably linked to the City of San Francisco’s housing aspirations. In a local news interview, he said the panel “spent nearly a year and produced four pages that don’t have any data in them at all… It is as though the outcome was preordained. They knew what the mayor wanted and they provided… And that’s troubling because people’s health is at risk.” The only way to be certain of the land’s safety for residence, according to Hirsch, is deep soil testing. This would require authorities to notify the development’s majority- mid-income residents, scare off buyers and potentially stop the redevelopment and gentrification of Bayview-Hunters Point in its tracks, a blow to Lennar and the city itself. Nevertheless, taking new samples is a crucial step in listening to the Black working-class residents who have been bearing the brunt of the Navy’s negligence for decades, but in the most gentrified metropolitan area in the country, both Lennar and the city of San Francisco seem to be unwilling to take this risk for fear of disillusioning their new residents.

The tenth lawsuit following falling housing prices in the new housing complex stated that Tetra Tech, Lennar, and developer Five Point Holdings LLC, which soon after scrapped its business plans with Lennar, covered up knowledge of industrial and radioactive waste nearby when selling and marketing new homes. The intersection of city, corporate, and military interests has allowed for the manipulation of aspiring homeowners in an area where a household income of $117,400 is considered low-income. Nevertheless, a lawsuit from the new complex is not enough to reconcile the damage done in Bayview-Hunters Point.

BLACK LABOR AND RESISTANCE

Lennar, Tetra Tech, and the Navy owe even more to the Black community. Local activists have been blowing the whistle on the military-industrial complex in Bayview for decades, and their suspicions arose not from plummeting housing prices but from illness and the abrupt end of their livelihoods.

When the Navy bought the shipyard from private owners just before the Pearl Harbor attacks, a slew of Black workers migrated from the South to take up new shipbuilding jobs at the newly acquired Hunters Point Naval Shipyard. Newcomers, molded by the ruthlessness of Southern Jim Crow and empowered by war-economy wages, lifted up the existing Black population by cultivating a sense of community as the neighborhood set upon a pathway to the middle class. But the Navy’s exit in 1974 ripped the community’s economic foundation out from underneath it, leaving the Black labor to which it owed its successes with little besides contaminated soil. Out of the ruins came activists and community leaders including the “Big Five of Bayview,” a coalition of Black women and outspoken mothers backing key neighborhood redevelopment projects in the 1960s and 70s. The group included Osceola Washington, who fundraised for youth alongside Black baseball legend Willie Mays; Elouise Westbrook, who advocated for safe, affordable housing following the displacement of low-income families after the redevelopment plans were revealed; Ruth Williams, who prevented the demolition of a historic opera house that now bares her name; and Julia Comer, who led the demolition and replacement of the substandard public housing established by the Navy. Other activists noted as part of the “Big Five” include Ardith Nichols, Rosalie Williams, and Bertha Freeman, who paved the way for successors like Espanola Jackson and Marie Harrison, the former taking the helm in demonstrations that led to the establishment of the San Francisco Human Rights Commission and the latter an environmental organizer and champion for Hunters Point during the cleanup scandal until her death from interstitial lung disease, a byproduct of the environmental racism against which she spent her life fighting.

As the city’s population grows, the Black population dwindles, and the nuclear system, with its history of exploiting Black labor dating to uranium mining in the Dutch Congo, adds to the immense stress of Black people living in one of the last neighborhoods to remain untouched by gentrification.

The untested sites at Hunters Point are a continuation of this bureaucratic violence. Although there currently aren’t plans to buy off longtime residents, it’s reasonable to anticipate a plan to “redevelop” the rest of the neighborhood. When this time comes, will residents finally receive consultation and soil tests, only to be displaced? Today, residents of Hunters Point live insecurely and without the peace of mind that comes from environmental health. In late 2018 the EPA criticized the Navy for a lack of transparency and for failing to specify how various radioactive elements would be identified in a retesting plan. This lack of transparency has fostered a sense of uncertainty that has persisted for far too long. It’s time to listen and make sure development and long-overdue testing does not lead to displacement. “We may not speak the King’s English,” Harrison said, “but we know what’s happening to us. We see it and live it everyday, so if you want to know about it, ask us, don’t ask somebody else because they don’t live here.” As the city’s population grows, the Black population dwindles, and the nuclear system, with its history of exploiting Black labor dating to uranium mining in the Dutch Congo, adds to the immense stress of Black people living in one of the last neighborhoods to remain untouched by gentrification.

If the City of San Francisco cannot make amends with the residents of Bayview-Hunters Point, its promises to advance racial equity will never be fully realized. If the military doesn’t own up to the negligence and injustices of the past, we cannot expect that the government will be responsible with the nuclear weapons development programs they want to reboot today. This neighborhood is sounding the alarm on the pervasiveness of nuclear injustice on city and national levels. It’s time for us to listen.

Sofia Guerra is a fellow at Beyond the Bomb from the Bay Area. She studies asymmetric operations, nuclear policy, and migration as a political science student at Amherst College.

ADVERTISEMENT: Hot, sexy Asians in your area! Are you looking for a petite, docile China Doll™ to welcome into your life? One who is exotic like a lotus blossom and energizing like a dragon, ready to breathe fire and lighten up your world!? Well, look no further: These Asian women meet all the criteria AND can help you relax with some aromatherapy or a deep tissue massage!

Oh.. wait… what’s that? You thought I meant that kind of massage? Sorry to break it to you, but we aren’t that kind of massage parlor. If you’re looking for a good time with some big d*ck energy, then might I recommend the local nuclear silo just down the road, instead? Talk about some BOMBSHELLS over there. No, really.

If you’re drawn towards the Anna May Wong-style “Dragon Lady” based off of the female villain in the “Terry and the Pirates” comics, then believe me, nuclear weapons are where it’s at now. These weapons are menacing yet alluring, an ego boost to the highest degree if you can attain one. They’re something to be conquered, particularly by the white man. To rein in their deviousness, of course, but also to rein in the deviousness of others by showing them your power over these women… I mean weapons. If you’re not careful though, the gratification can become addicting. Oh, but it won’t be your fault! It’s obviously the weapons’ fault for being so intoxicating. Everyone has bad days and deserves to let off some steam, and everyone lets off their steam in different ways. I let off my steam by teasing the nuclear button while you let off your steam by going to “massage parlors” — ideally Korean if you’re allowed to be picky, but then again it doesn’t matter all that much because they all look the same anyway. Again, it’s not your fault! But be aware that sometimes a “bad day” can start to blur the lines between a lust to violate and a lust to murder. Perhaps that’s what happened in Atlanta.

But race has nothing to do with it, right!? Not all of the victims in Atlanta were Asian. If we used a nuclear weapon against China, not all of the casualties would be Asian, either. Any other ole tourist or expat wandering around in the wrong place at the wrong time could get wiped off the face of the Earth alongside a disproportionate number of Asian victims, thereby absolving the crime of any racial implications. Any addiction to certain types of power fantasies are independent of race and history, anyway. If we do end up nuking China, it’s because they asked for it. They’re a threat to world order, a true “yellow peril” whom we must knock down a peg or two through manipulation using our domestic and foreign policy. If that doesn’t work, well, then, we’ll just resort to more carnal measures.

But yeah, we aren’t racist. Your family has a long history of interracial couples with Asian women dating back to at least the Korean War — NOT racist! And my hobby of keeping an eagle eye on China comes from my grandfather who kept his eyes on Japan — NOT racist.

So what if American military personnel in Japan during World War II did rape over 10,000 women during a three-month occupation in Okinawa? And so what if then that sexual exploitation was brought home by the War Bride Act, which allowed these men to bring their Japanese wives back to the states? It’s not like the importation of these women came with the importation of cultural stereotypes as well. I mean, who’s ever heard of Nancy Kwan’s character in “The World of Susie Wong” or Anna May Wong’s early films like “The Thief of Bagdad” or “Daughter of the Dragon”? People like us love the idea of dominance, sexual or otherwise, but hate it when our women suddenly want to make the rules for themselves. And then they even want to get paid for their sexual labor!?

Look, the US did decide to use a nuclear weapon for the first and only times in combat on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Sure, lots of reputable sources say it was unnecessary as Japan was already on the brink of surrender. And sure, those sources also say the proposition that the atomic bombs saved half a million American lives is vastly overinflated. But what’s most important to keep in mind is that we won. We got to have the thrill of the climax, of the “click” then “BOOM.”

So what am I trying to say again…? Oh, right. Come to our massage parlor if you’re looking for a good time but not a “good time.” We’ll highlight the sexualization of our Asian, female employees to draw you in and then submit to your hyper-masculinization of conflict, violence and dominance. [But for a real “ka-boom,” look no further than these weapons of mass destruction: Nuclear weapons. And then, if you don’t like who you are after all of the fantasies, just remember that however you respond next has nothing to do with race.]

Molly Hurley is a Nuclear Program Fellow with The Prospect Hill Foundation and Fellowship Associate with Beyond the Bomb. She is Chinese American as well as both “dragon” and “lady” in her fight against injustices but is neither in her relationship with men.

Jackie Waight is the Youth Services Coordinator at the Little Tokyo Service Center of Los Angeles, a co-chair of the WCAPS Human Rights Working Group, and is a Spring Fellow at Beyond the Bomb. She is a biracial Vietnamese American that breathes flames of radical change and bears wings of hope against the cultures and systems of injustice.

Lily Tang is a Chinese American and a first-generation college student at UMass Amherst studying Political Science & Global Studies, with concentrations in Asian/Asian American Studies & Civic Engagement. Lily sinks her claws in de-orientalizing Asian Studies and combating racial inequities to build a safer world for people of the global majority.

The image that appears in the body of this piece is a cover from Vogue Magazine published February 1, 1923.

The title image is “Long Mei,” by Molly Hurley. Clothed in just a single robe from a traditional Chinese hanfu, this woman is covered in scales and bears an uncanny resemblance to Anna May Wong. Ink, colored pencil, and alcohol marker on paper.

The United States holds one of the world’s largest nuclear arsenals, has an advanced civil nuclear program, and plays a leading role in global nuclear diplomacy. US nuclear policy has a direct impact on international security, and Washington’s choices in the nuclear field have far-reaching consequences.

What then should the Biden administration prioritize when it comes to US nuclear policy? Inkstick asked Heather Williams, Vipin Narang, Beatrice Finh, and Togzhan Kassenova for their recommendations. They emphasized the need for effective diplomacy and multilateral engagement, nuanced rhetoric on nuclear matters, and changes in the US nuclear program.

Check out their detailed recommendations below:

Heather Williams, Stanton Nuclear Security Fellow, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Listen to Allies: Allies should be a main priority for all US nuclear policies going forward. The Biden administration has stated one of its top foreign policy priorities is rebuilding credibility with allies. Allies are not a monolith, but many have expressed concern about further nuclear reductions, arms control, or changes in the US nuclear posture. The administration will have to balance any arms control efforts with allies’ interests and concerns. This can be done through regular consultation with capitals, engaging allies in the Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament (CEND) initiative, and building relationships at both the working and senior levels in the new administration.

- Prepare for the NPT Review Conference (RevCon): This happens every five years and was meant to happen in 2020, but the delay to August 2021 presents an important opportunity for the Biden administration to articulate its commitment to arms control and multilateralism. It should also immediately engage with NATO allies to discuss NATO’s nuclear mission, among other things, and prepare to present a united position on nuclear deterrence and disarmament at the RevCon.

- Start work on a New START follow-on: The Biden administration should immediately engage with Moscow to work toward a framework agreement for a future arms control agreement with Russia. This might include warhead reductions, non-strategic nuclear weapons, or hypersonic missiles. Many of these will present unique verification challenges and will take time to negotiate, so work should begin immediately on identifying areas of shared interest. Additionally, the administration should strongly encourage Russia (and China) to participate in the International Partnership for Nuclear Disarmament Verification (IPNDV) to promote shared understandings of verification activities.

Vipin Narang, Associate Professor of Political Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Remove W76-2 SLBM from Deployment: The deployed W76-2 is a new low-yield submarine launched nuclear weapon emplaced alongside multiple high yield weapons on the same type of missile on the same submarine. It creates a so-called “discrimination problem” which is more than just an adversary’s inability to determine if an incoming warhead is high or low yield — it is in fact a deterrence problem because the discrimination problem renders the W76-2 completely unusable.

- Prioritize Arms Control and Nonproliferation Agreements: Now that New START received a clean five year extension, work toward additional agreements to limit Russian tactical nuclear weapons deployments and review possibilities for further strategic nuclear caps, or deterrence at even lower numbers to further reduce systemic nuclear risks. The Biden administration should also return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) immediately, while focusing on strengthening and lengthening the agreement in follow-on negotiations. The window for a clean return to the JCPOA is closing with presidential elections in Iran looming in June.

- Improve Messaging: The Biden administration should not use the phrase “denuclearization of North Korea,” which was coined by the Trump administration and one of former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s favorite phrases — and which Kim Jong Un never agreed to. Instead, the administration should focus on reducing nuclear risks in North Korea, such as slowing its vertical proliferation, and deterring and disincentivizing North Korea from selling its wares abroad. More importantly, President Biden’s team should devise an approach that better reflects these necessary actions. Even if the rhetorical end goal remains “complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula” every day that passes without an agreement to limit North Korea’s growing arsenal is a day Kim Jong Un has to expand and improve it.

Beatrice Fihn, Executive Director, International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons

- Join the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW): As the first multilateral nuclear disarmament treaty to be concluded in over two decades, the TPNW is a significant milestone in efforts to reduce and eliminate nuclear weapons, and should be viewed and welcomed as an opportunity to make concrete progress on solving one of the most devastating threats to global security today. The treaty, which bans nuclear weapons, entered into force on January 22, 2021 and has the support of the majority of the world’s nations. It makes all activities related to nuclear weapons illegal under international law and requires states that have joined to provide assistance to victims of nuclear weapon use and testing and to remediate contaminated environments. It will advance the norm against nuclear weapons, chipping away at the legitimacy that a couple dozen states still ascribe to them. President Biden can sign the TPNW and submit it to the Senate for ratification, establishing himself as a progressive moral leader and increasing pressure on getting all nuclear armed states to the negotiating table.

- Redivert Spending on Nuclear Weapons: The TPNW bans its states-parties from developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, transferring, possessing, stockpiling, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons, or allowing nuclear weapons to be stationed on their territory. While the United States is not legally bound to adhere to these prohibitions since it hasn’t joined the treaty (yet), it should take steps to stop engaging in activities that have now been outlawed under international law. As a first order of business, the Biden administration should stop developing and producing new nuclear weapons systems and re-divert the billions of dollars the United States is projected to waste each year of his presidency on new weapons of mass destruction to address security issues Americans face including climate change, racial injustice, and the ongoing COVID–19 pandemic.

- Negotiate Further Reductions of Nuclear Weapons Stockpiles: The world might be relieved that President Donald Trump no longer controls one of the largest nuclear arsenals in the world, but the risk of nuclear weapons use with catastrophic humanitarian consequences remains as long as nuclear weapons exist. With emerging technologies and an increasing complex and unpredictable international security situation, the risk of nuclear weapons use will only increase over time. In the first five days of his administration, Biden agreed with Russian President Vladmir Putin to extend New START, maintaining the 2010 agreed caps on their arsenals. Now the Biden administration needs to use the coming four years to negotiate and implement further and deeper cuts in global nuclear stockpiles to ensure the world is safer at the end of this term. Every nuclear weapon eliminated is one that cannot unleash the scale of human suffering unseen since the 1945 bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and would be a step closer to protecting the United States and the world from possible catastrophe.

Togzhan Kassenova, Senior Fellow, Center for Policy Research, University at Albany, State University of New York

- Repair the Diplomatic Damage: Words matter. Over the last four years, US nuclear diplomacy took a major hit. In addition to walking out of treaties and agreements, it was the arrogant and condescending tone often employed by senior nuclear officials in speaking and writing that damaged US standing on the global nuclear scene. President Biden’s picks for top State Department positions provide optimism that US nuclear diplomacy will revert to a professional and respectful manner of engaging other countries on nuclear matters.

- Ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT): A global ban on nuclear tests will serve US national security and contribute to international security. Helping to bring the ban into force is also the right thing to do for moral reasons — entire communities in different parts of the world are still paying the price for the nuclear tests conducted by nuclear powers. Over the decades, President Biden has shown support for the CTBT. For example, when he was a senator, Biden encouraged fellow lawmakers to ratify the CTBT. As vice president in the Obama administration, he made the case for the CTBT ratification. Now, as president, he can use his standing to promote the ratification of this important treaty by the US Congress.

- Convert US Naval Reactors to Low-Enriched Uranium (LEU): The United States runs its nuclear submarines on highly-enriched uranium (HEU). By switching its fleet to LEU, the United States will help its own cause of promoting HEU minimization worldwide. Less HEU in the world also lowers the risk that it can be stolen and used in a nuclear terrorist act.

Check out more in the series:

After the Apocalypse: Cybersecurity

After the Apocalypse: Iran

After the Apocalypse: Climate Crisis

After the Apocalypse: US Grand Strategy

After the Apocalypse: China

On February 6, 1968, Dr. King, stepped up to the pulpit to warn against the use of nuclear weapons. Addressing the second mobilization of the Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam, King urged an end to the war and warned that if the United States used nuclear weapons in Vietnam the earth would be transformed into an inferno that “even the mind of Dante could not envision.”

Then, as he had done so many times before, King made clear the connection between the black freedom struggle in America and the need for nuclear disarmament: “These two issues are tied together in many, many ways. It is a wonderful thing to work to integrate lunch counters, public accommodations, and schools. But it would be rather absurd to work to get schools and lunch counters integrated and not be concerned with the survival of a world in which to integrate.”