Three years ago this month, I had the opportunity to do something most Americans will never do: I visited the Islamic Republic of Iran. I was one member of a peace delegation organized by the women-led human rights group Code Pink. Twelve of us traveled from Chicago, Florida, Kentucky, Michigan, New York, San Francisco, and Hawaii to meet Iranians and see their country for ourselves — or as much as we could, given the restrictions on our movement.

Traveling to Iran with an American passport has never been easy during the last four decades, but in 2019, a year when the United States and Iran appeared to be on a collision course toward a possible military confrontation, the odds of receiving a visa from the Islamic Republic appeared slim to none. Yet, despite the open hostility and bellicose rhetoric, we were granted visas, allowing us to land at Tehran’s Imam Khomeini International Airport on Oct. 19, 2019.

Throughout our stay, we were warmly received as we traveled from Tehran in the north to Shiraz in the south. Iranians were surprised to meet Americans who, they said, they hadn’t seen in years. “Welcome to Iran!” was a common greeting as people thanked us for visiting their country, even as our president threatened to destroy them.

Many Iranians made it clear that their animus toward the US government and its foreign policies was not directed at all American citizens. Indeed, the Iranians we met were pleased to encounter a group of Americans who were interested enough in their country to visit and learn about the Persian culture they were so proud of.

Three weeks after our group left Iran, the country erupted in nationwide anti-government protests sparked by an overnight 50% spike in fuel prices. However, such periodic paroxysms in Iran are complicated and have deep roots fed by political, social, and economic factors. The 2019 protests and subsequent government crackdown were said to be the most strident since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, with many hundreds killed, injured, and arrested.

Nearly three years later, following the brutal killing of Jina “Mahsa” Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman who died shortly after being arrested by Iran’s “morality police” for wearing the mandatory hijab (head covering) loosely, Iran has again erupted in convulsions of rage. This time the demonstrations have been led by women and teenage girls (and joined by men) who are outraged not just by the brutal murder of Amini (and now many others) but by decades of being denied the most basic human rights.

The reaction of Iranian authorities and the paramilitary pro-government Basij militia that have tried to snuff out protests with a brutal, violent crackdown, censorship, internet blackouts, and outrageous murders, rapes, and widespread brutality against their fellow citizens, is regrettably unsurprising. It is also profoundly frustrating and sad to watch helplessly as the long-suffering Iranian people are subject to more savagery, and it makes me think about those I encountered three years ago.

While in Iran, I met women from all walks of life — religious minorities, students, shopkeepers, interpreters, musicians, educators, and administrators. They were as varied as can be imagined in outlook and experience. Their appearance reflected a range of individuals, just as it does around the world. In public, most women wore a manteau, a kind of semi-loose overcoat that rides to mid-thigh, suggesting a degree of modesty depending on how it is worn.

I saw women with showy scarves color-coordinated with stylish outfits, girls in vibrant floral tops, and at least one schoolgirl wearing a baseball cap with “ROCK” spelled out in rhinestones. Some women adhered to hijab standards closely, and other luxuriously coiffed women had the sheerest of scarves scarcely covering their flowing golden blonde locks, faces accented with pomegranate red lipstick and thick eyelashes. One of the only places I saw women dressed in all-concealing head-to-toe black chadors were the government employees scurrying from their offices at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs complex at the end of the workday.

On my first day in Iran, I saw two young women, maybe 18 years old, posing for a selfie. One wore a deep plumb-colored head scarf, modest in its bulk but riding far back on her head. Her friend wore black sneakers and skinny jeans that left her ankles bare. Her black hijab sat far back on her head, revealing straight black hair that fell like a wave over blushing cheeks and bright red lipstick. Where were these girls now, I wondered. Had they been stopped by the “morality police,” arrested, abused, or worse?

It is also profoundly frustrating and sad to watch helplessly as the long-suffering Iranian people are subject to more savagery, and it makes me think about those who I encountered three years ago.

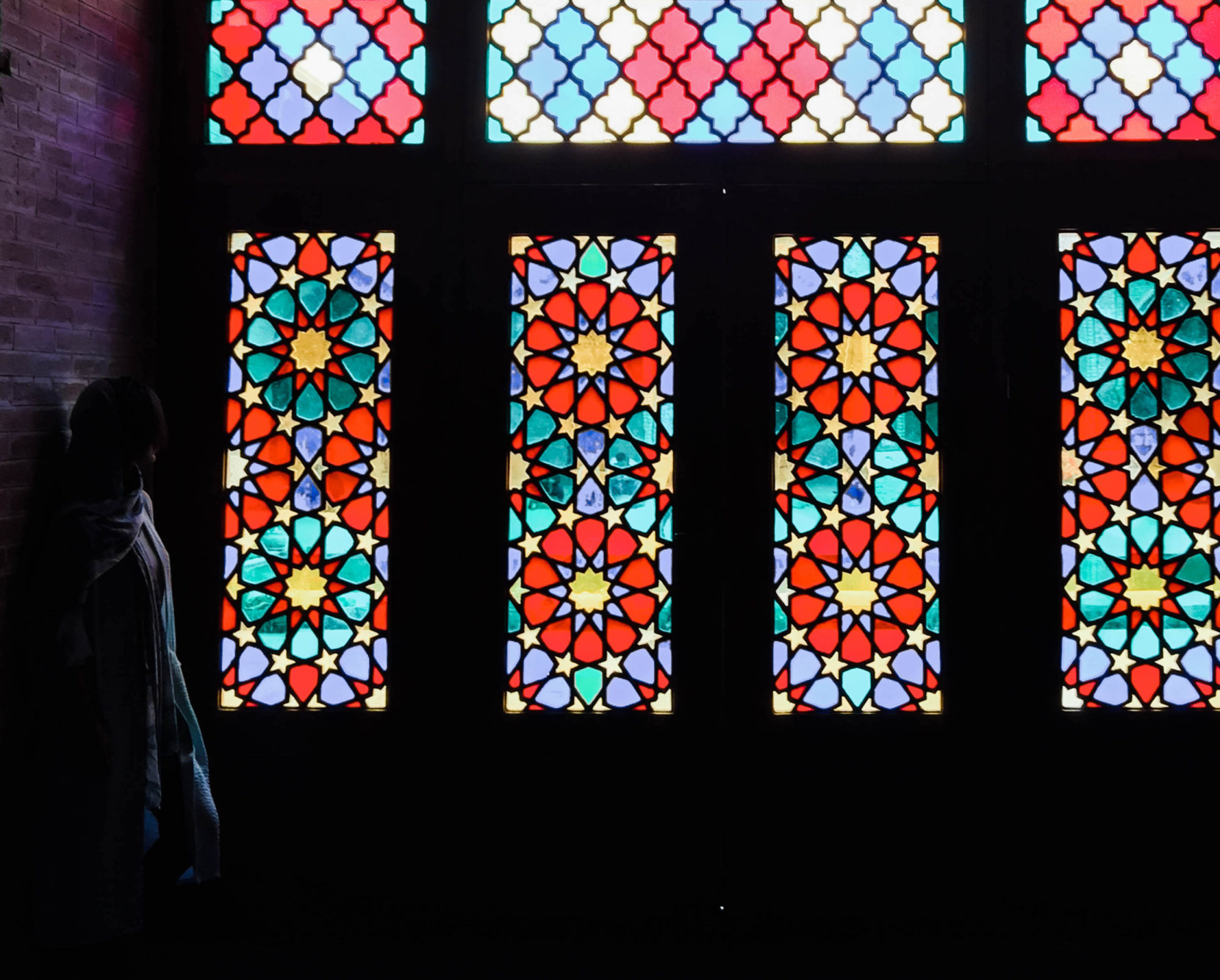

A few days later, while in Isfahan, we stopped at a simple tea shop in a small courtyard. High walls created a private space hidden from the leafy tree-lined street beyond. Resting inside this small oasis, we stirred glasses of hot black chayee with nabat — saffron-flavored rock candy sticks. When I went to the counter in front of the kitchen, a young Iranian woman took my order, her hijab draped over her shoulders like a scarf worn on a cool autumn day, which it was. Nothing about her fully exposed, free-flowing hair was remarkable except for how ordinary it was and how carefree she appeared. Inside this de facto hijab-free zone, people just went about the business of sipping hot tea and chatting with friends beneath skinny trees with their leaves mostly fallen. Now I wonder how this young woman and her friends are doing three years later, on these violent autumn days.

On our final day in Iran, in the southern city of Shiraz, together with one of my American colleagues — Beth from upstate New York— we ordered tea in a small shop near an ornate sprawling Persian garden. Blowing on our tea to cool it, our eyes caught a family of five seated at a table, charging their phones and drinking tea. We struck up one of those well-intentioned but not particularly fluent conversations one has with people they meet while traveling when neither party speaks the other’s language. Lots of smiling, nodding, and single-word sentences: Hello. Iran. Good? Yes. America. Your children?

The mother told us they were visiting from the Shia pilgrimage city of Qom in the north. Two sons, maybe nine or ten years old, smiled and were giggly but spoke no English. Their sister, who spoke English well, told us she was thirteen. She wore a very loose grey full-length frock that fit like a tent with a bulky two-toned grey headscarf that looked far too thick for that warm October day.

Maybe because we were foreigners, the girl from Qom seized the opportunity to practice her language skills, telling us about herself, gesturing as she fixed her slipping hijab. She told us that she didn’t like the hijab or the government, indicating her displeasure. She explained that she played the piano and dreamed of someday traveling to Austria to study music. She sighed heavily, saying she didn’t think she would ever make it to Austria. It’s too difficult and too expensive, she said.

The girl from Qom looked sad but beamed when Beth asked her to take a picture together. In the photos we took with the family, the girl’s hijab had fallen (or she’d pulled it down), exposing her hair completely, if only briefly in that most unlikely of encounters.

Later that day, after visiting the tomb of the beloved Persian poet Hafez, I ducked into a shop where four girls were selling books of poetry and souvenirs. I struck up a conversation with one of the girls who spoke English as she helped me select a leatherbound copy of the “Divan of Hafez.” We made small talk, and before I departed, as I had with a number of other people I’d met in Iran, we exchanged Instagram accounts as one would share business cards — a way to keep in touch.

Three years later, I periodically receive updates from this young woman who I’ll call “Zahra.” Zahra tells me what’s happening in Iran and the suffering she and others are enduring. She expresses her frustration, anger, and sadness. Overwhelmed with a sense of being trapped in Iran, Zahra tells me she and many others are thinking of killing themselves if their protests don’t achieve the change they seek.

“There’s no future in this country, and I can’t emigrate to another country because of poverty.”

Trying to encourage her, I tell her that change will come eventually and that many people support Iranian’s struggle for freedom, but writing that feels hollow. I ask her what people outside of Iran can do to help.

“There’s not too much that you can do,” Zahra responds, “but you can be our voice…”

“They don’t want to get arrested, tortured, raped in prison because of [their] beliefs. They want freedom of speech. Freedom of thought. Freedom of religion. Freedom of expression. Basic human rights that everyone [has] in democratic countries.”

“Shirin”

I also checked in with a man I befriended in Iran three years ago through social media. The man — I will call him “Amir”— lives in a town not far from Tehran with his wife and their 16-year-old daughter — the same age as the girl from Qom, who was also the age of Sarina Esmailzadeh and Nika Shakarami, two Iranian girls violently brutalized and killed by Iranian security forces in the current protests that began in September 2022.

As the father of a teenage girl, I ask Amir how he feels.

“In one word, I can say ‘insecure.’” Amir explains that his daughter’s classmates had been detained for protesting. The girls had been taken some place, their phones had been taken away, and no one could contact them. The girls were not beaten but had been verbally harassed. The situation in Iran now, Amir says, makes his heartache, and he is angry. Really angry.

What’s different in the current protests, compared with others in the recent past, Amir says, is that many Iranian celebrities who had previously remained silent are now speaking out in support of the people. Feeling they have nothing left to lose, the people are no longer afraid.

This week I also checked in on a woman in Tehran who I’ll call “Shirin.” Thirty-one-year-old Shirin is frustrated to see the current protests being misrepresented. She says the protests are not about attempting to revive the Iran nuclear deal, which she says would not benefit ordinary people. According to Shirin, most Iranians hate the nuclear deal because it only helps the government, not the people. “Of course, some of the people thought the nuclear deal [would] help the economic situation in Iran, but nothing happened, and things got worse and worse,” she wrote.

In Iranian public opinion polling, conducted by the Center for International Security Studies at Maryland between 2015 and 2022, those who “strongly” or “somewhat” approved of the deal fell from 75.5% to just over 47%, while those who “strongly” or “somewhat” disapproved of the deal rose from 20.6% to over 47%.

She says Iranians want complete regime change, adding that those who formerly supported the regime no longer do. “They also want the regime to change because they have seen that in this past 20 years, nothing changed. During Ahmadinejad, Rouhani, Raisi, nothing changed, and EVERYTHING got worse,” she writes.

Iran’s demands are simple, Shirin says. They just want basic human rights. “[We] want the freedom of what to wear. If you want to wear hijab, you can wear. If you don’t, you don’t wear.”

She continues: “They don’t want to get arrested, tortured, raped in prison because of [their] beliefs. They want freedom of speech. Freedom of thought. Freedom of religion. Freedom of expression. Basic human rights that everyone [has] in democratic countries.”

Although Shirin hasn’t been able to connect to the Internet on her phone for three weeks, she can use a VPN at work. In the evening, she says there’s no internet after 4 p.m., sometimes until the next morning. She adds there is talk that the government might shut down the internet completely, but she can’t be sure what will happen.

Shirin’s message, punctuated by a crying emoji, reads: “Women here are very alone. We want help. We want support.”

Sharing stories on social media, she says, is a big help. “We want the people around the world to be our voice.” In all caps, she repeats: “BE OUR VOICE.”

In her closing message, she implores me, “Please just don’t mention my name. Now it’s a very sensitive situation.”

All names of Iranian individuals mentioned in this article have been changed to protect their identities.