The worst of the fighting has left the capital for now, but the city remains tense. Giant steel anti-tank barriers called “hedgehogs” stand in rows scattered every 500 meters like menacing games of jacks, positioned to block Russian invaders. Damaged and destroyed buildings dot the city, and suburbs like Irpin and Bucha have become known worldwide as grim settings for brutal carnage.

In Kyiv, life continues as residents walk their dogs on warm spring days and some restaurants and cafés have reopened but things are far from normal, and nothing is certain. A short stroll from the presidential palace, seated at a wooden corner desk in his home, Vladimir Dmitrievich Parkhomenko, taps his laptop and sips green tea with apricot jam.

Vladimir Dmitrievich has lived on the seventh floor of this flat with his wife Nelli since 1984. In response to a reporter’s questions, he replies, “You propose to walk through my life like the keys of an accordion. I haven’t done this for a long time.”

Part scientist, part poet, part philosopher, Vladimir Dmitrievich continues, “You are returning me to my history, making me think of the amazing laws of life.”

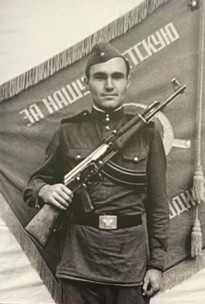

Husband, father, grandfather, Vladimir Dmitrievich has led an active and productive life working as a chemical engineer, professor, administrator, technology and education minister, and diplomat. During Soviet times he was a member of the VAK (Higher Attestation Commission), an administrative agency that awards advanced academic degrees. At 88 years old, he continues to serve as an advisor to the director of the Ukrainian Institute of Scientific and Technical Expertise and Information and edits the journal Science, Technology, Innovation.

Vova, as his wife calls him, reflects on the past saying, “the meaning of my life is not just a list of random events.” Filled with the winds of creativity, he says, I am co-author of this life. Part scientist, part poet, part philosopher, Vladimir Dmitrievich continues, “You are returning me to my history, making me think of the amazing laws of life.”

In 1933, during the Holodomor, a genocide that killed millions of Ukrainians through famine blamed on the forced collectivization of land under Joseph Stalin, Vladimir Dmitrievich’s life was saved before he was even born. His maternal uncle, a soldier fighting against the Basmachi resistance, called his sister (Vladimir’s mother) to move to a village near the Turkmen capital Ashgabat where Vladimir Dmitrievich was born.

He still vividly remembers the village where he grew up. He says there were no books save for a bible. Vladimir Dmitrievich was raised by strict grandparents, but with a soul and heart filled with diligence, openness, and moral clarity. They instilled in him an understanding of responsibility and strong work ethic.

Throughout his life, he has loved to study and teach. As a researcher, he took great joy in solving hidden riddles. “I have always loved science,” he says. He also loved the challenge of mastering skills, adopting new ideas, and constantly learning scientific and pedagogical concepts.